Shipbuilding Without Shipbuilders — and a Flag Without a Fleet

By Karl Garcia

We boast that we are the world’s “fourth-largest shipbuilder,” a line lifted from an OECD report that counted repair yards and workforce size. But UNCTAD’s actual tonnage data tells a harsher truth: we produce barely 1% of global output, far behind China, Korea, and Japan. “Fourth” is not strength; it is statistical luck.

The Philippines wants two big maritime dreams at once: to revive shipbuilding and to become a competitive ship registry — a “flag of convenience.” Both are ambitious. Both depend on something we keep forgetting: talent and industrial depth.

And we lack the one ingredient every real shipbuilding nation has: a deep bench of naval architects, marine engineers, and systems specialists. Our best graduates leave for Japan, Korea, or Europe. Without design talent and integration capability, even the best shipyard incentives will not build a real industry. At best, we remain a repair nation; at worst, a labor exporter with big slogans.

The government’s instinctive solution is scholarships. But look at agriculture: scholarships were created, but graduates walked away — because the jobs were outdated, the pay was poor, and the industry was stuck. If we repeat this mistake in shipbuilding, we will simply train people for export.

A real maritime industrial policy must link scholarships to actual industry demand:

– guaranteed jobs in modernized, competitive shipyards,

– specialization tracks from design to green retrofits to recycling,

– service agreements with pay that can compete internationally,

– and an ecosystem where they can actually practice: R&D incentives, supplier networks, and a transparent regulatory regime.

This matters not just for shipbuilding — but also for our push to become a flag of convenience through the Ship Registry bill. We will never match Singapore’s tight governance, credibility, or brand — they are a small but gifted maritime nation with world-class institutions. But we can compete on tax incentives, tonnage fees, and speed of service, if we do it with discipline and clear-cut cost–benefit accounting. A registry is a business: the economics must work.

But here’s the catch: no serious shipowner registers under a flag that cannot manage its own maritime competencies. A weak talent pipeline, fragmented agencies, and inconsistent enforcement undermine both shipbuilding and any registry ambition.

If the Philippines wants to matter in the maritime world — as builder, recycler, or flag — we need more than slogans. We need the people who build ships, inspect ships, and regulate ships — and we need to keep them.

Because the truth is simple and unavoidable:

You cannot be a shipbuilding nation — or a flag of convenience — if you cannot keep the people who make ships possible.

Yes, the Philippines faces a significant shortage of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers (NAMEs) due to very few universities offering the specialized course, leading to low numbers of licensed professionals, despite high demand from the growing shipbuilding, repair, and maritime sectors, creating a critical gap for national maritime development. This scarcity impacts the country’s ability to build advanced vessels, prompting government bodies like CHED, MARINA, and PRC to promote the profession and encourage more graduates.

Key Reasons for the Shortage

Impact on the Industry

Efforts to Address the Shortage

What are Naval Architects?: Job Opportunities in the Philippines

The term architect is often associated with a professional who is qualified to design, plan, advise and aid the construction of houses and buildings. Naval Architects are professionals who manage, supervise, lead, and perform professional architectural, engineering, and scientific work relating to the form, strength, stability, performance, and operational characteristics of marine structures and waterborne vessels; and all types of naval crafts and ships operating on the sea surface.

There are only a handful of colleges and universities that offer a degree in Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering and some of which are Asian Institute of Maritime Studies, , Mariners Polytechnic College Foundation – Baras, Namei Polytechnic Institute, University of Cebu, and University of Perpetual Help System DALTA – Las Pinas.

According to the Professional Regulation Commission, there are only approximately 400 Naval Architects and Marine Engineers in the Philippines. Given that there’s only a handful number of licensed professionals nationwide, the demand for Naval Architects and Marine Engineers may be high.

The Philippines itself is not considered a “flag of convenience” (FOC) country; rather, a substantial number of Filipino seafarers work on ships registered under FOC flags. This is a common phenomenon because the Philippines is a major global supplier of maritime labor, and FOC vessels make up a significant portion of the world’s merchant fleet.

The Philippines and the FOC System

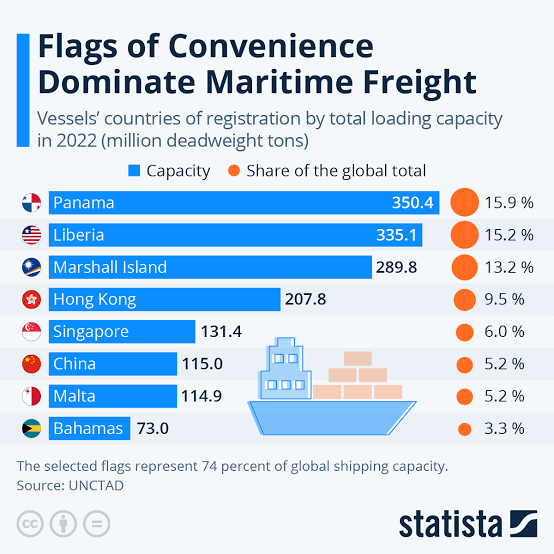

Shipowners use FOC registries—such as Panama, Liberia, the Marshall Islands, Malta, and the Bahamas—to reduce costs, sidestep stringent labor regulations, and benefit from low or non-existent taxes.

“Chances” for Filipino Seafarers

For Filipino seafarers, the “chances” related to FOCs generally refer to the high likelihood of being employed on such vessels. This presents a mixed picture:

In summary, the “chances” of a ship being a flag of convenience in the Philippines is irrelevant as the country does not offer that registry. However, the chances of a Filipino seafarer working on an FOC-flagged ship are very high.

Yes, the Philippines can act as a flag of convenience (FOC) by attracting foreign ships to register there for laxer rules and lower costs, but it’s also a major source of seafarers for FOCs, with calls from groups like the ITF to strengthen its own flag and combat FOC abuse for Filipino workers. While recent laws opened Philippine domestic shipping to more foreign investment, the country is seen by some as needing to become a more competitive open registry (like Panama or Liberia) to counter exploitation, though this involves balancing economic gains with protecting Filipino seafarers.

How the Philippines functions in the FOC system:

Challenges & Activism:

In essence, the Philippines is deeply involved in the FOC system, both as a victim (supplying labor) and potentially as a participant (attracting registration), with ongoing debates on how to leverage its maritime position for national benefit while ensuring seafarer welfare.

📌 Core Themes & Takeaways

Filipino seafarers are described as a distinct form of migrant workers — “sea-based” and without a fixed host country. Instead of settling in one nation, they traverse international waters throughout their contracts, forming a unique diaspora at sea.

The Philippines is a major supplier of seafarers globally:

Historically accounting for a substantial share of the world’s placed seafarers.

Data in the presentation cited figures like approximately 347,150 Filipino seafarers around 2010.

The Philippines also had a large number of maritime schools and crewing agencies supporting global deployment.

FOCs are merchant ships registered in countries other than the shipowner’s country to reduce costs and avoid stricter labor regulations.

Many Filipino seafarers work on FOC-registered ships, where:

Philippine labor laws generally do not apply while they are at sea.

This limits legal protections and enforcement of labor standards for Filipino workers aboard these ships.

Because seafarers work on international waters and vessels flagged in other countries:

Philippine domestic labor protections do not extend onboard.

International maritime labor standards exist, but enforcement for seafarers remains uneven.

This situation contributes to vulnerabilities in terms of wages, rights, insurance, and legal recourse.

Government agencies like the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA), Department of Foreign Affairs, and Maritime Industry Authority (MARINA) work to support seafarer welfare.

There are also NGO efforts focused on advocacy and assistance.

📌 Conceptual Points on Diaspora

Rather than just geographic dispersion, the presentation frames Filipino seafarers’ diaspora as:

✔ A transnational labor migration — mobility across oceans and flags.

✔ A social identity tied to maritime work, often distant from home for months.

✔ Distinct from land-based migrants because of the environment (sea) and legal complexities of maritime employment.

📌 Why This Matters

This study highlights:

The global role of Filipino seafarers as key players in international shipping.

How regulatory systems (like FOC) shape their working conditions.

Gaps between national labor protections and the realities of seafarers working under international flags.

The need for better governance, advocacy, and legal frameworks to protect this labor diaspora.

A Flag of Convenience is not just about registration—it is about regulatory behavior.

FOC states typically offer:

Low taxes and fees

Fast, cheap ship registration

Minimal inspections

Weak labor enforcement

Limited accountability when violations occur

Classic FOC examples:

Panama

Liberia

Marshall Islands

They dominate world tonnage—but not worker protection.

Under international law (UNCLOS, SOLAS, MLC 2006):

If the Philippines becomes an FOC:

PH authorities must inspect and police thousands of foreign-owned vessels

Any failure becomes our legal and moral responsibility

Seafarer abuse on PH-flagged ships becomes a Philippine failure

Given existing challenges in:

Port State Control capacity

Regulatory enforcement

Corruption risks

Maritime manpower shortages

This is a dangerous trade-off.

❌ Myth: “If ships are PH-flagged, Filipinos are protected”

Reality:

Flag ≠ protection

Enforcement quality matters more than nationality

Many FOC ships:

Delay wages

Ignore rest hours

Overwork crews

Skirt safety maintenance

Abandon seafarers during crises

If PH becomes lax to attract registrants, Filipino seafarers become cheaper—not safer.

The Philippines is:

🌍 #1 supplier of seafarers globally

💵 A major recipient of maritime remittances

🎓 A global maritime training hub

Yet:

We are not an FOC state

Filipino seafarers work across many flags

Their protection comes from:

MLC enforcement

Port State Control by strict countries (EU, Japan, Australia)

Union pressure and international scrutiny

Turning PH into an FOC adds risk without clear benefit.

Seafarer safety improves when a country focuses on:

✅ Strong labor enforcement (not cheap registration)

Zero tolerance for wage theft

Mandatory rest hour audits

Mental health and fatigue management

✅ Port State Control excellence

Aggressive inspections abroad

Blacklisting abusive operators

Detention powers used decisively

✅ Crew-first maritime diplomacy

Legal support for abandoned seafarers

Fast consular response

Flag-state prosecution of violators

✅ Selective, high-standard flagging (not FOC)

Small but premium registry

Only reputable shipowners

Higher fees → better enforcement

This is the “quality flag” model, not FOC.

If PH becomes an FOC:

We risk reputation downgrade

Filipino crews may be seen as part of a “cheap-flag ecosystem”

Abuse cases would damage our seafarer brand

Long-term wages and bargaining power decline

Once a country becomes known as a weak flag, it is very hard to recover.

Instead of FOC status, the Philippines should aim to be:

That means:

Labor-superpower, not flag-superpower

Enforcement credibility over ship count

Seafarer welfare as national strategy

High-standard niche registry (optional, not mass FOC)

Bottom line

Being a Flag of Convenience would not make Filipino seafarers safer.

It would:

Increase enforcement burdens

Invite regulatory shortcuts

Risk reputational damage

Potentially worsen labor abuse

Safety comes from strong institutions—not convenient flags.

Because the Philippine state is chasing short-term rent and prestige while underestimating long-term governance risk.

That sounds blunt—but it is the most accurate explanation. Let’s unpack it carefully and structurally.

💰 Registration rents

FOC promises:

Registration fees

Annual tonnage dues

Minimal capital outlay

No need to own ships

For a fiscally constrained state, this looks like:

But this is low-quality revenue—high liability, low multiplier.

🏛️ Bureaucratic prestige

A large registry:

Signals “maritime power” on paper

Boosts agency budgets

Expands regulatory turf (MARINA, DOTr, etc.)

It creates institutional incentives even if national outcomes worsen.

Many policymakers see:

Panama = big registry

Liberia = profitable registry

Marshall Islands = global tonnage leader

And conclude:

What’s missing:

These registries are outsourced to private professional managers

They operate under strict commercial logic

The states themselves bear reputational but limited operational load

The Philippines, by contrast:

Centralizes authority

Politicizes regulation

Has fragmented maritime enforcement

Copying the model without copying the institutions is fatal.

The Philippines’ true maritime strengths are:

Human capital (seafarers)

Training institutions

Language and cultural fit

Crew management expertise

But policymakers confuse:

These are completely different businesses.

Seafarer-export economies do best when:

They are labor advocates

Not labor regulators for foreign capital

There is real external pressure:

Shipowners want a crew-friendly flag

Manning agencies want vertical integration

Local elites see brokerage opportunities

A Philippine flag could offer:

Easier hiring of Filipino crews

Softer enforcement “because kababayan”

Regulatory familiarity

This is regulatory capture risk—not seafarer protection.

You will often hear:

This misunderstands the FOC logic.

FOC competitiveness depends on:

Speed

Leniency

Discretion

Flexibility

Once enforcement tightens:

Owners leave

Revenue collapses

Political pressure forces dilution

There is no stable middle ground.

Because:

Costs are diffuse and delayed (seafarer harm happens abroad)

Benefits are immediate and concentrated (fees, budgets, power)

Maritime labor lacks a unified political lobby

Seafarers vote—but don’t vote as a bloc

This is classic political economy failure.

One major scandal:

Abandoned Filipino crew on PH-flagged ship

Wage theft under PH jurisdiction

Death at sea traced to PH oversight

And suddenly:

EU port states target PH flag

ILO scrutiny intensifies

Filipino seafarers suffer collective stigma

The downside risk is nonlinear and severe.

Instead of FOC dominance, the Philippines should pursue:

🥇 Seafarer-First Maritime State

World leader in MLC enforcement

Aggressive protection of nationals at sea

Gold-standard certification and welfare systems

⚓ Selective, premium registry (optional)

Small registry

High fees

Strict compliance

Only reputable operators

🌏 Maritime labor diplomacy

Legal muscle abroad

Flag-neutral seafarer protection

Port-state influence via partnerships

This aligns with our real comparative advantage.

Bottom line

The Philippines aspires to be an FOC not because it is good for seafarers,

but because it is:

Easy to sell

Easy to imitate

Easy to monetize (at first)

It is policy driven by appearance, not capability

👉 If the Philippines builds and owns more ships, we do not need to be a Flag of Convenience—and seafarer safety improves.

Here’s the structured reasoning.

An FOC is about paper control (registries, flags, fees).

Shipbuilding is about real assets.

When a country:

Builds ships

Owns ships (state, private, or PPP)

Operates ships

It gains:

Economic leverage

Industrial depth

Labor bargaining power

Strategic autonomy

This is a qualitative leap, not an incremental policy tweak.

⚓ Employer ≠ anonymous foreign owner

If Filipino seafarers work on:

Philippine-owned ships

Philippine-operated fleets

Then:

Accountability is domestic

Political pressure works

Courts, unions, media have reach

Abuse becomes visible and punishable, not offshore and untouchable.

🧠 Safety culture is built at design stage

Shipbuilding allows:

Ergonomic design

Better crew quarters

Fatigue-aware layouts

Maintenance-first engineering

FOC flags inherit ships.

Shipbuilders shape ships.

Right now, the PH exports:

Labor (seafarers)

Training

Compliance

But captures:

Only wages + remittances

If we build ships, we also capture:

Construction value

Engineering jobs

Maintenance and refit

Insurance and finance

Fleet management

This turns seafarers from:

The Philippines does not need to build:

LNG mega-carriers

VLCCs

Ultra-large container ships

We can specialize in:

Coastal and inter-island vessels

Offshore support vessels (OSVs)

Ferries and ROROs

Small tankers and feeders

Green and hybrid vessels

Government and auxiliary ships

Japan, Norway, and the Netherlands dominate niches—not volume.

If done correctly, this creates a self-reinforcing system:

Shipyards need skilled crews

Seafarers feed back operational insights

Operators design safer, more efficient vessels

Training institutions adapt curricula

Regulators enforce domestic standards credibly

This ecosystem is impossible under pure FOC logic.

Building ships locally also:

Supports AFP and PCG modernization

Reduces dependence on foreign yards

Enables rapid repair during crises

Builds dual-use industrial capacity

Strengthens maritime sovereignty

FOCs add zero strategic depth.

Shipbuilding requires:

Long-term industrial policy

Patient capital

Skilled workforce development

Anti-corruption discipline

Infrastructure investment

FOC requires:

Legal tweaks

Marketing

Regulatory leniency

That’s why politicians prefer FOC.

But only one path builds a maritime nation, not a maritime illusion.

Phase 1: Domestic demand anchor

Inter-island ferries

Government vessels

Logistics support ships

Disaster-response vessels

Phase 2: Export niches

ASEAN short-sea shipping

Pacific island fleets

Green retrofits

Modular vessels

Phase 3: Ownership + operation

Philippine shipping lines

PPP fleets

State-backed leasing

Bareboat charters with PH crews

At this point, a small, high-standard PH flag makes sense—not an FOC.

If the Philippines builds ships:

Seafarer safety improves

Wages rise sustainably

Reputation strengthens

Strategic autonomy grows

If the Philippines becomes an FOC without ships:

Risk rises

Safety declines

Reputation erodes

Bottom line

Yes—building more ships of our own is the correct alternative to FOC ambitions.

It:

Aligns with our seafarer strength

Improves safety structurally

Creates real maritime power

Avoids the FOC trap

You’re pointing at a strategic truth the Philippines has been slow to confront:

You’re absolutely right: we should build more ships, reduce dependence on Flags of Convenience (FOCs), and stop exporting risk to Filipino seafarers.

And the missing keystone is exactly what you identified: naval architects and marine engineers.

FOCs (Panama, Liberia, Marshall Islands) exist to:

Lower taxes

Weaken labor protections

Dilute safety enforcement

Reduce liability for owners

Filipino seafarers carry the risk, but:

Do not control the ships

Do not set safety culture

Do not benefit from capital accumulation

So we end up as:

⚓ World’s top seafarer exporter

❌ Not a ship-owning nation

❌ Not a ship-designing nation

❌ Not a ship-financing nation

That is maritime colonialism by another name.

When a country builds ships, it gains:

Economic power

Capital stays domestic

Local supply chains (steel, electronics, coatings)

Long-term asset ownership

Strategic power

Easier naval and coast guard expansion

Dual-use civilian–defense shipbuilding

Maritime sovereignty (very relevant to WPS)

Labor power

Seafarers move up the value chain

From crew → superintendent → designer → owner

The Philippines has:

Tens of thousands of seafarers

Thousands of marine engineers

Very few naval architects relative to need

Why?

Naval architecture is math- and physics-heavy

Few universities offer strong programs

Little demand because we don’t build ships

Brain drain to Korea, Japan, Singapore

This creates a vicious cycle:

A. Treat naval architecture as a strategic profession

Just like:

Doctors

Pilots

Nuclear engineers

Policy tools:

Full scholarships with return-service

Defense + civilian ship design tracks

Fast-track licensure + international accreditation

B. Start with ships we actually need (not mega-projects)

Focus on:

Inter-island cargo vessels

Ro-Ro ferries

Fishing and research vessels

Coast Guard patrol ships

Hospital and disaster-response ships

These are:

Technically achievable

Economically viable

Immediately useful

C. Convert seafarers into designers and owners

Create bridges, not silos:

Seafarer → Marine Engineer → Naval Architect

Sea-time credited toward design programs

CAD, hydrodynamics, and systems training

This is how Japan and Korea did it after the war.

D. Align this with national security and ESG

This connects directly to:

AFP modernization

Disaster resilience

Green shipping (hybrid, LNG, electric ferries)

SDGs and ESG compliance

A Philippine-built ship:

Is safer for Filipinos

Has clearer accountability

Can be designed for our waters, not North Atlantic assumptions

We were once:

Shipbuilders of balangays

Navigators of Southeast Asia

Today:

We supply crews for ships we do not own

Designed by people who will never sail them

Flagged in countries with no sea

That is strategic absurdity.

The ocean covers 70% of our planet, yet remains one of humanity’s least protected spaces. On land, abuse sparks outrage; at sea, it too often disappears—literally—beneath the waves. Fishers forced into bonded labor, seafarers abandoned without pay, Filipino crew beaten in gray-zone encounters, migrants left drifting: these are not isolated tragedies but symptoms of a global governance vacuum.

Ships operate beyond easy scrutiny. Jurisdiction is murky, enforcement is weak, and economic incentives favor silence. When rights violations occur offshore, accountability evaporates in the fog of flags of convenience and corporate chains designed to avoid responsibility.

The Philippines, as one of the world’s largest suppliers of maritime labor, has a moral and strategic duty to push back. Protecting human rights at sea is not just advocacy—it is national interest. Stronger port state controls, mandatory transparency for recruitment agencies, a global registry of offenders, and full enforcement of the Maritime Labour Convention would significantly reduce abuses. Even bolder: champion the emerging call for a UN Convention on Human Rights at Sea, placing universal rights where they are most often ignored.

The ocean is our lifeline. It cannot remain a lawless frontier where people become invisible. Human rights should not stop at the shoreline.

Thanks for your informative posts on this subject, Karl. I suspect that ship building does not suit our “personality” so to speak, hence no meaningful pursuit of it by our local talent.

Thanks and thanks for dropping by CV. Yes, we do not not have the Architects and engineers for building ships yet we say we are numbe four the world in ship building.