Governing Space, People, and Power: Why the Philippines Keeps Solving the Wrong Problems

By Karl Garcia

The Philippines does not suffer from a shortage of plans. It suffers from a failure to govern space, power, and time.

From traffic decongestion to housing relocation, from community schools to fisheries management, from health devolution to climate resilience, the same pattern repeats: technically sound ideas are introduced into a political system structurally incapable of sustaining them. What follows is not reform, but fragmentation—pilot projects without scale, promises without permanence, and solutions that collapse under vested interests.

This is not accidental. It is systemic.

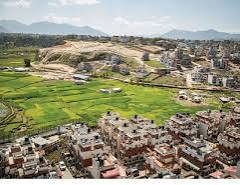

Land Without a Law, Cities Without a Plan

At the center of this dysfunction lies the country’s most enduring legislative failure: the absence of a National Land Use Act (NLUA). For decades, its passage has been blocked—ironically, most fiercely by local government units that frame opposition as “local autonomy,” but in practice defend discretionary power over zoning, land conversion, and reclassification.

This discretion has become the oxygen of speculation, patronage, and corruption.

Without a binding national framework, land is allocated not by ecological logic, disaster risk, or economic efficiency, but by political convenience. Floodplains become subdivisions. Transport corridors are severed by gated developments. Schools, clinics, evacuation centers, and fisheries infrastructure are displaced by speculative real estate.

Urban planner Felino “Jun” Palafox Jr. warned of this outcome for decades. His proposals—integrated transport, mixed-use density, green belts, disaster-resilient urban form, and balanced regional development—were repeatedly praised, selectively adopted, and ultimately ignored. Not because they were flawed, but because they threatened a political economy built on fragmented control.

The result is urban decay disguised as growth.

Decongestion, Relocation, and the Myth of Moving People Without Moving Power

Nowhere is this clearer than in Metro Manila’s chronic congestion. MMDA decongestion plans, satellite cities, and near-city relocation schemes are announced every administration. Almost all fail.

Families are “relocated” to distant or poorly serviced areas with no jobs, transport, schools, clinics, or social networks. Many quietly return to informal settlements closer to opportunity. Others are trapped in peripheral poverty—counted as housing successes but lived as economic failures.

Even recent near-city relocation initiatives repeat the same mistake: housing without livelihoods, infrastructure without governance.

Contrast this with Indonesia’s decision to relocate its capital to Nusantara. Whatever its risks, it recognizes a truth Philippine policy avoids: congestion is not solved by moving people alone, but by redistributing state functions, investment, and power. Without that, decongestion is merely displacement.

Waste, Ruins, and the Refusal to Think Regeneratively

The same linear thinking plagues environmental policy. Demolition debris from disasters, old infrastructure, and urban renewal is dumped into landfills, exacerbating flooding and pollution. Abandoned subdivisions—failed speculative projects—are left to rot.

Yet globally, landfill remediation, debris recycling, and brownfield conversion are not only possible but productive. Properly treated, former dumpsites and abandoned developments can be rehabilitated for agriculture, agroforestry, solar farms, wetlands, or community facilities. This requires remediation science, land-use planning, and long time horizons—precisely what fragmented governance cannot provide.

A regenerative economy demands patience. Philippine politics rewards speed, optics, and turnover.

Devolution Without Guardrails: Health and Education as Casualties

Nowhere is the cost of this fragmentation more human than in health and education.

Barangay health stations and community schools were never meant to operate in isolation. They were designed as nodes—linking prevention, nutrition, livelihoods, culture, and trust in the state. Figures like Jose V. Aguilar proved that community-rooted systems work when protected institutionally.

But devolution without guardrails hollowed them out.

Health budgets drift toward buildings and ribbon-cutting projects rather than prevention. Community hospitals lose doctors not because of shortages, but because they are professionally isolated and structurally abandoned. Big hospitals consolidate, triage becomes financial filtering, and the poor are quietly excluded.

Education followed a similar path. Community schools were absorbed into centralized bureaucracy. Mother-tongue instruction—effective in stable communities—was implemented rigidly in a now mobile, multilingual country. The principle was sound; the governance was not.

AI now raises the stakes further. Poorly governed, it will recentralize power and deepen inequality. Properly governed, it could strengthen local systems—if institutions are capable of adaptation. At present, they are not.

Fisheries and the Illusion of Local Control

Coastal governance exposes the same structural flaw. Community Fisheries and Coastal Resource Management works—until it collides with power.

Small fishers comply with conservation rules while commercial operators intrude with impunity. Foreign coercion in the West Philippine Sea further shrinks access. The result is not ecological failure, but political unfairness.

The emerging Blue Economy framework could correct this—or repeat the pattern. Without explicit protection for small fishers, financing will flow to capital-intensive projects, while communities absorb risk and lose space. A blue economy that displaces its poorest stakeholders is not sustainable; it is extractive.

Corruption Is Not a Side Problem—It Is the System

Across sectors, corruption is not merely bribery. It is embedded in discretionary approvals, opaque planning, regulatory capture, and the absence of enforceable national frameworks. It thrives where responsibility is devolved but accountability is not.

This is why the same reforms keep failing:

- Land use without a national law

- Decongestion without economic redistribution

- Relocation without livelihoods

- Community systems without institutional protection

- Sustainability without power reform

The Unifying Failure—and the Way Forward

The Philippines’ central problem is not technical incompetence. It is governance incoherence.

A regenerative, inclusive future requires aligning:

- Land use with ecology and risk

- Urban planning with livelihoods

- Devolution with accountability

- Community systems with national protection

- Economic growth with long-term stewardship

This means confronting politically uncomfortable truths:

- A National Land Use Act is non-negotiable

- Anti-dynasty reform is a development policy

- Community institutions must be insulated from capture

- Sustainability requires saying no—to speculation, shortcuts, and performative reform

The country already has the knowledge, the pilots, and the blueprints. What it lacks is the willingness to govern beyond election cycles and vested interests.

Until space, power, and people are planned together, the Philippines will keep mistaking motion for progress—and promises for reform.

The problem is no longer what we should do.

It is whether we are willing to break the system that prevents us from doing it.

Happy New Year! I asked ChatGPT to make a combined thematic synthesis of ALL your recent articles and this is what came out:

I asked ChatGPT for a more detailed summary and got this:

Thanks for the synthesis. Which yoi do superbly even before chatgpt.

Many thanks for these Irineo. Happy 2026!

Dystopian stories endure not because they predict the future, but because they diagnose the present. Wall-E, The Hunger Games, Planet of the Apes, Soylent Green, Terminator, and Mission: Impossible warn what happens when ecology, technology, governance, and social trust fail.

Jared Diamond reminds us civilizations collapse not from invasion alone, but from environmental mismanagement, elite blindness, and institutional rigidity. In the Philippines, climate vulnerability, archipelagic geography, dense cities, inequality, and strategic exposure make these lessons urgent.

Inequality is a threat multiplier. Dynastic politics, oligarchic capture, and unequal access to education, healthcare, and technology weaken resilience. The Hunger Games dramatizes how extractive institutions concentrate power while leaving ordinary people exposed. True resilience demands inclusive institutions, accountable governance, and genuine social mobility.

Technology and health amplify the risk. Terminator and Mission: Impossible warn against delegating judgment to systems without oversight. Pandemics, biotech inequality, and environmental degradation show how knowledge becomes power—unless it is shared and regulated responsibly. Plastic, floods, and waste highlight that resilience must be systemic, upstream, and preventive.

Other stories sharpen the lesson. Chernobyl is about institutional lying; The Wire exposes how misaligned incentives cripple institutions; Andor shows the quiet growth of authoritarianism; The Lord of the Rings and Seven Samurai teach that enduring systems and collective action matter more than individual heroes.

Nearly every dystopia shares the same root causes: short-term leadership, institutional decay, elite insulation, and public disengagement. Avoiding collapse does not require heroics—it requires systems people understand, trust, and can hold accountable.

The Philippines has had enough lessons—from television, film, books, and real life. All we need now is a leader who can orchestrate and conduct, and citizens willing to play the music.

The Philippines faces a convergence of threats: climate disasters, economic shocks, weak institutions, cyber risks, and geopolitical pressures. Yet our response remains fragmented and reactive. Modern systemic collapse rarely strikes as a single event—it unfolds silently, as failures in environment, economy, governance, technology, and security compound.

The Philippine National Resilience Framework (PNRF) offers a roadmap to prevent collapse rather than merely respond. It rests on five pillars:

Climate and Environmental Security – Protect ecosystems, mandate local adaptation plans, and integrate climate risk into national planning to reduce disaster-related deaths and preserve livelihoods.

Inclusive Economic Institutions – Enforce competition, develop resilient industries, expand social protection, and ensure strategic sectors serve public needs.

Governance and Rule of Law – Digitize courts, professionalize civil service, accelerate anti-corruption efforts, and strengthen oversight to ensure continuity and public trust.

Technology and Cyber Governance – Regulate AI, strengthen cybersecurity, combat disinformation, and close the digital divide for both security and inclusion.

Strategic and Maritime Security – Integrate maritime data across civilian and military agencies to protect sovereignty, food security, and disaster response.

To make these pillars work as a system, the PNRF proposes two integrative institutions: the National Strategic Integration Office (NSIO) and the Maritime Fusion Center (MFC). The NSIO ensures policies are coherent, anticipatory, and cross-sectoral. The MFC fuses maritime awareness across agencies, providing a unified picture of threats and opportunities at sea. Together, they prevent fragmented, siloed governance from amplifying risks.

The Philippines has endured enough crises. Lessons alone are insufficient. We need institutions that can orchestrate complexity, anticipate cascading failures, and maintain continuity beyond electoral cycles. The PNRF is not a theoretical plan—it is a strategic imperative. By acting now, the Philippines can shift from reaction to anticipation, from fragmentation to integration, and from vulnerability to resilience.

The question is simple: will we continue to stumble from crisis to crisis, or will we build a nation capable of enduring and thriving amid converging risks? The answer depends on national resolve and integrated action today

Community Hospitals Without the Brain Drain

Community hospitals can coexist with large tertiary hospitals and public health offices without bleeding doctors—but only if the system is designed for complementarity, not competition. When poorly designed, big hospitals hoard talent and community facilities become revolving doors. When designed well, each level does what it does best—and doctors stay.

This matters deeply in the Philippines, where rural and community hospitals chronically lose physicians not because they are small, but because they are isolated, undervalued, and career-limiting.

The first fix is clear role definition. Community hospitals should not imitate tertiary centers. Their strength lies in primary care, maternal and child health, chronic disease management, geriatrics, prevention, and stabilization with referral. Big hospitals, meanwhile, should focus on complex surgery, subspecialty care, ICUs, teaching, and research. When community hospitals are forced to do tertiary work, doctors leave. When they are respected as frontline specialists, doctors stay.

Second, doctors should not be forced to choose between “big” and “small” hospitals. A rotational and shared staffing system allows physicians to spend part of the week in tertiary hospitals and part in community facilities. Specialists can run scheduled outreach clinics, and junior doctors can rotate early in their careers. This keeps skills sharp, reduces overload in big hospitals, and removes the stigma that community service is professional exile.

Third, career progression must be protected. Community-based service should count toward residency slots, subspecialty training, plantilla promotions, scholarships, and research opportunities. Service must translate into advancement—not sacrifice. Doctors avoid community hospitals when they see a dead end; they commit when service opens doors.

Fourth, public health officers must act as clinical anchors, not mere bureaucrats. Municipal and provincial health officers should lead community hospital networks, with authority over referrals, workforce deployment, and local health priorities—while paperwork is streamlined across DOH, PhilHealth, and LGUs. Doctors stay when leadership is medical, not purely administrative.

Fifth, retention does not require matching private-sector pay. What works is financial stability and quality of life: predictable government salaries or capitation, modest performance incentives, housing and transport support, loan forgiveness, and family-friendly benefits. Predictable income plus humane working conditions beats higher pay with burnout.

Sixth, the system must strengthen referral pathways, not rivalry. Mandatory feedback loops, shared medical records, clear escalation protocols, and mutual respect between institutions reduce frustration and professional alienation. Doctors disengage when referrals are rejected or ignored; they commit when treated as partners.

Finally, doctors must be trained for community medicine, not just assigned to it. Medical education should embed students early in community hospitals and elevate family medicine, geriatrics, and public health as prestigious tracks. Doctors tend to stay where they were trained to belong.

Bottom line: Community hospitals don’t lose doctors because they are small. They lose doctors because they are isolated and undervalued. They thrive when roles are clear, careers are protected, doctors rotate instead of being exiled, public health officers lead clinically, and big hospitals act as partners—not magnets.

Design the system right, and doctors won’t have to choose between service and a future.

The crisis in Philippine fisheries is not only environmental—it is political. Declining fish stocks, coastal degradation, and climate stress unfold within a system shaped by unequal power: between small fishers and large commercial operators, and between the Philippine state and stronger maritime actors in contested waters.

Community Fisheries and Coastal Resource Management (CFCRM) has shown that recovery is possible when communities hold real authority. Across the country, locally managed marine sanctuaries, mangrove co-management, and women-led monitoring initiatives have restored ecosystems and livelihoods. Small-scale fishers, whose survival depends on healthy seas, are often the most consistent stewards. Community management is not a soft alternative to regulation; it is the foundation that makes rules legitimate and enforceable.

Yet community gains are steadily undermined. Domestically, large commercial fishers—often politically connected—continue to encroach into municipal waters despite legal prohibitions. With superior vessels and influence, they evade sanctions while small fishers face strict local enforcement. This imbalance erodes trust, compliance, and the credibility of CFCRM itself. The legacy of AFMA deepens the problem: fisheries were sidelined, underfunded, and treated as secondary to agriculture, leaving small fishers structurally marginalized.

Externally, coercion at sea compounds these pressures. In the West Philippine Sea, Chinese harassment—along with enforcement actions by other regional states—has reduced access to traditional fishing grounds. For coastal communities, geopolitics means lost income, rising risk, and abandoned livelihoods. Even the best community governance collapses when fishers cannot safely fish.

These realities expose a hard truth: fisheries management cannot be separated from maritime security and political economy. Small fishers are not only food producers; they are civilian stakeholders whose presence sustains both ecosystems and sovereign rights.

This is where the proposed Blue Economy Bill matters. If anchored in CFCRM, it can protect community fishing grounds, curb commercial encroachment, and channel financing toward cooperatives, insurance, cold chains, and climate resilience. If not, it risks becoming another trillion-peso vision that bypasses the poorest fishers while rewarding scale and capital.

A viable blue economy must confront power asymmetry head-on. Sustainability cannot be built on “survival of the fittest.” It requires governance that protects those who fish responsibly, asserts lawful use of national waters, and treats community stewardship as a public good. Without small fishers, there is no sustainable fishery—and no credible presence at sea.

Debates over mother-tongue instruction and community schools in the Philippines are often framed as tradition versus modernity. This misses the real issue: whether the country can recover a lost systems logic—education rooted in community life—while adapting to a nation reshaped by migration, land displacement, political concentration, and artificial intelligence.

At the center of this logic is Dr. Jose Vasquez Aguilar, not as nostalgia, but as proof that community-rooted reform once worked—and as a warning about how easily it can be undone.

Aguilar was not a Manila theorist. As division superintendent across Masbate, Cebu, Camarines Norte, Samar, Capiz, and Iloilo, he saw the same failures recur: weak comprehension, high dropout rates, curricula detached from daily life, and schooling that served elites better than communities. His response was the community school—education shared by teachers, parents, and local institutions, linked to livelihoods and local governance.

In Capiz, this was concrete. Schools integrated agricultural practice, including second cropping that raised farm productivity and household income. Education functioned as a development tool, not merely a credential pipeline.

Aguilar’s most controversial insight—later echoed by neuroscience—was simple: comprehension comes before cognition. His 1948 Bureau of Public Schools–approved experiment using Hiligaynon as a medium of instruction produced higher achievement, confidence, and participation.

What failed was not the idea, but the institution protecting it.

Community schools were gradually undermined by recentralization. Standardized barrio councils replaced organic local systems. Language policy reversals favored uniformity over evidence. The lesson is blunt: reforms without political protection are easily reversed, no matter how effective.

Today’s critics raise a valid concern. Barangays are no longer linguistically stable. Migration, urbanization, climate displacement, and mobile labor mean many communities no longer share a single mother tongue. But this does not invalidate Aguilar’s insight—it exposes the danger of rigid policy.

The core principle was never linguistic purity. It was learning anchored in lived reality. In a mobile, multilingual Philippines, policy must shift from “one barangay, one language” to flexible language access: bridge languages, multilingual scaffolding, and teacher-led adaptation based on real classrooms, not central decrees. Multilingual societies function through subsidiarity, not uniformity.

Artificial intelligence raises the stakes further. Poorly governed, AI will recentralize content, deskill teachers, and widen inequality. Properly governed, it can localize materials, support multilingual instruction, and strengthen—rather than replace—community schools. Technology is not the threat. Governance is.

The deeper barriers remain political. Dynastic control turns decentralization into local capture. Corruption thrives where oversight is weak. Land speculation and displacement uproot schools and communities alike, underscoring the urgency of a National Land Use Act that protects social infrastructure, not just markets.

Universal free education is necessary—but insufficient. Without safeguards, the well-off crowd out the poor, and “access” masks unequal outcomes. Equity requires strong community schools, targeted support, and institutions designed for inclusion rather than patronage.

Community schools matter because they operate where centralized systems fail—at the intersection of education, governance, land, and social trust. They absorb migration shocks, manage diversity, and anchor communities in a country that is constantly moving.

Aguilar showed this could work. What failed was the political will to defend it.

Mother-tongue education is not obsolete. What is obsolete is rigid policy, centralized control, and the belief that uniformity equals fairness. The Philippines does not need to choose between tradition and innovation. It needs systems that bend with change—without breaking communities in the process.

If the World Sends Our Workers Home

Trump’s failure to deport millions was not proof of safety; it was proof of constraint. A more ruthless leader, or a coordinated shift among countries, could still force mass returns. The Philippines must prepare for that worst case.

Overseas work exists because domestic systems failed to absorb labor. Calling OFWs “heroes” honors sacrifice but excuses inaction; blaming them for broken families avoids responsibility. Both narratives miss the point: labor export became a substitute for development.

The answer is not to trap workers at home, nor to panic when they return. It is to build a country worth staying in—without closing the door to leaving. Absorption means real industries, regional jobs, and clear pathways from overseas work to domestic roles, especially for seafarers who are strategic assets, not just remittance sources.

Mobility must remain a right. But dependence must end. If mass deportations come, the real failure will not be global politics—it will be our lack of preparation.

The Philippine Land Problem Is a Space Governance Failure

The Philippines’ persistent failures in housing, relocation, decongestion, food security, port development, and disaster resilience all point to a single underlying issue: the country does not govern space as a system.

Land is managed as fragmented property, not as national infrastructure. Decisions about housing, agriculture, transport, ports, and environmental protection are made in isolation—often by local governments operating under short-term political and fiscal incentives—without a binding national spatial framework. The result is a landscape that no longer works for the people who depend on it.

How the Breakdown Happened

Historically, land in the Philippines has been concentrated, politicized, and commodified—from colonial land grabbing to postwar reforms that preserved elite control. The Local Government Code accelerated fragmentation by devolving land-use powers before national rules were established. Zoning, reclassification, and conversion became discretionary tools rather than strategic instruments.

Instead of coordinating development, devolution turned land into a source of revenue, patronage, and political permanence. Agricultural land was converted ahead of demand, housing was built far from livelihoods, ports were approved without logistics integration, and settlements expanded into hazard zones.

Why Autonomy Made It Worse

Proposals for federalism or greater regional autonomy assume that proximity improves governance. In land use, the opposite often occurs. Without national spatial discipline, autonomy multiplies inconsistency. Regions compete through regulatory arbitrage, strategic assets are planned parochially, and political dynasties consolidate territorial control.

Land authority without architecture does not empower communities—it entrenches capture. Criminal and speculative capital embeds itself in property, turning land into a store of power rather than a platform for productivity.

Centralization Is Not the Answer Either

Re-centralizing decisions would not solve the problem. The failure is not where power is located, but that rules were never centralized while decisions were devolved. This inversion produced incoherence. Every land decision may be legal, yet collectively destructive.

The solution lies in centralizing the rules—national land classifications, hazard zones, agricultural protection, strategic corridors—while leaving site-specific decisions local. This restores coherence without reverting to authoritarian planning.

The Cost of Ungoverned Space

The paradox of the Philippines is abundance amid scarcity: idle housing alongside homelessness, vacant land amid congestion, displacement amid abandonment. Disaster recovery repeats the same spatial mistakes, demolishing and rebuilding instead of repairing and reusing.

These are not sectoral failures. They are signs of weakened state capacity, expressed physically. When land stops organizing life—connecting homes to work, farms to food, ports to trade—the state stops functioning spatially.

What Space Governance Means

Space governance is not about outer space. It is the collective management of land, territory, and human settlement as an integrated system. It aligns private land use with public survival—food security, climate safety, mobility, and national security.

Strong space governance limits discretion, not development. It disciplines land so people do not have to be displaced, exposed, or excluded.

The Narrowing Window

Land mistakes are permanent. Every unauthorized conversion, idle relocation site, and fragmented approval hardens dysfunction. The puzzle is still solvable—but only if land is treated as infrastructure, not inventory.

The question facing the Philippines is no longer ideological. It is whether the country can still reassemble itself spatially before land failure becomes irreversible.

Dumb R us, tag line for government.

https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1265950

DAR turns over P64-M farm-to-market road in Abra

https://opinion.inquirer.net/125485/farm-to-pocket-roads

ano ba yan! the road is only 1.85km long, less than two kilometers, correct ba yan?

if so, it is not very long for the price of 64millions. I reckoned the road is a bit too short for us to be singing and dancing and celebrating!

My gosh I think we aint seen nothin yet in the DPWH magic

Farm to market roads are corruption con jobs used by LGUs to generate commissions. They are last and worst investments for the nation.

The Philippines’ housing crisis is not only about scarcity but also waste. While millions lack decent homes, thousands of condominiums, relocation houses, military housing units, and brownfield sites remain idle or abandoned. These failed developments reflect systemic problems—poor location choices, missing infrastructure, weak coordination among agencies, and housing designs that people simply will not accept.

Yet these idle assets also present a major opportunity. Vacant urban condos can be converted into retirement and senior-living facilities, abandoned public housing can shift from ownership to rental or mixed-use redevelopment, and brownfields can be transformed into climate-resilient, transit-oriented communities. Emerging coordination among DHSUD, NHA, PRA, DOT, DENR, LGUs, and the private sector shows that a national adaptive-reuse strategy is possible.

By prioritizing reuse over new construction, strengthening interagency governance, and empowering local governments, the Philippines can turn housing wastelands into inclusive, productive communities—addressing social need, economic efficiency, and environmental sustainability at the same time.

We own a small condo in Cebu for our convenience there. I’d guess of nearly 1,000 units 50% are owned by investors who try to rent them out, 30% are lived in by owners or held as second residences, and 20% are vacant or on the market for sale. I think it will be a rough few years for those hoping to rent theirs out due to lousy tourism volumes and BPOs likely to shrink. If banks have big exposure on loans, the Philippines may have its very own RE bubble.

” If banks have big exposure on loans, the Philippines may have its very own RE bubble.”

———–

So true, when regulators fail, lending practices may lead to asset bubble. Thailand had this issue as well as the US.

I think here banks direct regulators rather than the other way around. So the regulators let banks pool their bad loans to get them off the books, then the regulators disappear them in some magic way, I suspect using taxpayer money. One never knows how much the system can process, but it seems to work.

https://www.cnbc.com/2025/12/31/ai-data-centers-debt-sam-altman-elon-musk-mark-zuckerberg.html

“Oracle’s view from the jobsite is simpler: the demand is real, diversified, and already spoken for.

“We see broad-based demand across a huge swath of the industry, so it’s not just from any one individual place,” Clay Magouyrk, Oracle’s newly elevated co-CEO, told CNBC in West Texas in September. “I don’t worry about a bubble, because I see committed demand for it.””

I think I’ll go with that for now. It’s all pretty exciting. The scale is jawdropping. The future will be surreal by today’s old clunky standards. We are the cowboys. They are the aliens. Just wow!

Happy New Year, Joe!

Thank’s Karl, happy 2026 to you. May it be a good year for you and yours, and may we all get a little wiser and have fun doing it. 🙂

Appreciated much! Let us all have fun in getting wiser.

Yes — there are confirmed cases and ongoing investigations in the Philippines involving Chinese nationals acquiring Philippine land through falsified documents, fake citizenship claims, and use of dummies — but the full scale and legal conclusions are still being worked out by authorities. Here’s a clear summary of what’s publicly known from credible reports:

🇵🇭 What’s Happening: Foreign Ownership Laws vs Falsification

🔹 Philippine law about foreign land ownership

The 1987 Constitution prohibits foreign nationals from owning land in the Philippines.

Foreigners can only have land via a Philippine corporation that is at least 60% Filipino-owned, subject to other legal requirements.

Using “dummies” — Filipino citizens acting as fronts to hide foreign ownership — is prohibited under the Anti-Dummy Law.

🔹 Cases involving Chinese nationals and falsification

Several high-profile cases and legislative probes show patterns where Chinese nationals allegedly used falsified Philippine documents — such as birth certificates and passports — to obtain land. �

Philstar.com +1

📌 Key examples:

House joint committee findings (2024): Lawmakers submitted documents to the Office of the Solicitor General (OSG) alleging Chinese nationals bought thousands of hectares of land in Central Luzon (especially Pampanga) using questionable documents and citizenship claims. Some individuals were said to hold hundreds of titles and set up corporations purportedly Filipino-owned. �

Philstar.com +1

Willie Ong / Empire 999 case: A Chinese national allegedly held up to ~300 land titles and is linked in media reports to dubious land ownership and criminal activity. �

BusinessWorld

Aedy Tai Yang: Another individual implicated in falsifying documents to claim Filipino citizenship to acquire land and operate businesses. �

Philstar.com

Alice Guo and family: A separate case where a Chinese family (including a former mayor) was charged with falsification and violations of the Anti-Dummy Law for misrepresenting themselves as Filipino to buy multiple land parcels in Pangasinan. �

Newspapers +1

Immigration arrests: The Bureau of Immigration (BI) reports arresting individuals using fake Philippine identities, including birth certificates and business registrations, tied to land acquisition ventures. �

Philippine News Agency

📊 How Massive or Widespread Is It?

Short answer: There are numerous cases under investigation, but the full nationwide scale is not yet officially quantified by Philippine authorities.

❗ What we do know:

Lawmakers have suggested “thousands of hectares” of land may be involved based on preliminary inquiries, though exact verified figures have not been released. �

Philstar.com

Some investigations unearthed Chinese nationals with hundreds of titles in their names or corporate entities. �

BusinessWorld

Multiple government agencies (OSG, NBI, BI) are now reviewing titles, citizenship documents, and corporate records to determine legality. �

Philstar.com +1

What’s not yet clear:

The total hectares of land acquired via falsification nationwide

How many of those lands are still owned by foreign nationals

How many are legally enforceable cases or have been sealed in court

Authorities are still building legal cases, and some proposed laws (e.g., a Civil Forfeiture Act) aim to strengthen the government’s ability to seize illegally acquired land. �

Tribune

🧠 Why This Is a Big Deal

National security concerns: Allegations link land holdings to offshore gaming operators (POGOs) and potential illegal networks. �

Philstar.com

Economic & legal integrity: Ownership through falsification undermines Philippine constitutional limits on foreigners.

Rule of law: Prosecuting anti-dummy and falsification cases may shape how strictly property laws are enforced.

LGU’s are shitty business managers. They should be able to spot these abuses easily. Corruption blinds them I suppose.

Because LGUs are agaibst NLUA and are autonomous dynasties, they are causing problem after problem.

And the the too devolved line agency has to bow to the lgu too.

as regards lgu in bamban where alice guo was mayor, she was presumably very kind and generous to her constituents, gives hams on christmasses she did, gives school equipment to school kids too, she was much loved by many for her community initiatives that all turned out to be cover up for her involvement in large scale criminal activities. if not for risa hontiveros, we would never have known the real alice guo.

They know everything that happens in their kingdom.

kaso, lot of lgus did not know there were ghost flood projects in their area, they were not privy to dpwh internal activities. even the joy belmonte, the twice mayor of quezon city, sabi she did not know there were ghost projects in quezon city! (there were!) and she thought she knows everything that happens in her electorate, (she did not, apparently!)

“Looking the Other Way” Is Not Accidental — It’s Structural

What appears as temporary or permanent blindness across agencies and LGUs usually comes from four overlapping realities:

No single office owns the entire land transaction chain.

LCR / PSA → birth records, citizenship claims

DENR / LRA / Registry of Deeds → land classification and titling

LGUs → zoning, permits, tax declarations

HLURB / DHSUD / SEC → corporate structures

BI / DFA → immigration status

Each can plausibly say:

“That part wasn’t ours.”

This creates institutional neck contortion: everyone looks sideways, not forward.

Most illegal acquisitions are not crude. They use:

Filipino dummies with real IDs

Corporations that technically meet the 60–40 rule on paper

Naturalized or falsely documented “Filipinos”

Layered ownership across relatives, shell firms, and trusts

So staff don’t see “Chinese ownership” — they see:

“Complete documents”

“Proper notarization”

“No red flags in our checklist”

The system rewards procedural compliance, not substantive truth.

LGUs are especially vulnerable because:

Land transactions bring tax revenue

Large buyers stimulate construction, jobs, “development”

Political pressure discourages scrutiny

A mayor, assessor, or registrar who blocks a transaction:

Delays money

Upsets powerful interests

Risks reassignment, harassment, or isolation

So blindness becomes career-preserving eyesight.

Not all corruption is bribery.

Often it’s:

“Don’t ask, don’t tell”

“This came from above”

“It already passed another office”

“We’ll just process”

That’s how mass violations occur without mass arrests.

Why This Matters Beyond Land

This isn’t just about property. It connects to:

National security (land near ports, bases, infrastructure)

POGO and organized crime ecosystems

Urban distortion (housing unaffordability, speculative bubbles)

Rule of law erosion — where legality becomes a performance

Maybe looking the other way is green tape Then dogooders who get in the way are the ones blamed for red tape.

That pretty much nails LGUs as I see them.

“The country already has the knowledge, the pilots, and the blueprints. What it lacks is the willingness to govern beyond election cycles and vested interests.

Until space, power, and people are planned together, the Philippines will keep mistaking motion for progress—and promises for reform.

The problem is no longer what we should do.

It is whether we are willing to BREAK THE SYSTEM that prevents us from doing it.” – Karl

Any ideas from anyone on how to break the system?

The necessary steps are identified just before that concluding quote.

-Land use with ecology and risk

-Urban planning with livelihoods

-Devolution with accountability

-Community systems with national protection

-Economic growth with long-term stewardship

This means confronting politically uncomfortable truths:

-A National Land Use Act is non-negotiable

-Anti-dynasty reform is a development policy

-Community institutions must be insulated from capture

-Sustainability requires saying no—to speculation, shortcuts, and performative reform

Essentially the LGUs need to become civic institutions rather than dynastic milking cows. To end the political cycles as disruptive to progress, voters will have to become aware of the need to vote for character and competence over popularity, and the “good” liberal political force will have to win three presidential elections to provide 18 years of continuity to break the churn of politics and convert it to process and progress.

So the answers are:

1) Create an organized and well funded liberal political force.

2) Embark on a massive and continuous redefinition of patriotism and voter accountability.

3) Pass laws that bring civic competence, technology, and justice to the Philippines.

Thanks, JoeAm, but I was thinking along the lines of what is Karl said is lacking: “What it lacks is the WILLINGNESS etc …”

How do we get what is lacking?

As Karl points out: “The country ALREADY HAS the knowledge, the pilots, and the blueprints.” How do we get what Karl points out as lacking? Without the willingness, all the specifics that you have reiterated, will not, according to Karl, happen.

I wouod say elect he young ones to Malacanang but only Sotto.is worthy,.Leviste, etc need to eat more rice. Pag gusto may paraan, pag ayaw may dahilan.

leviste hits at the hip pocket, and his fellow solons seems to be ganging up on him! trying hard to discredit him.

anyhow, havent we seen enough of change (how ironic!) we got rid of the biggest scammer and sent him and his family spectacularly packing off to hawaii. but then, we got more of the same now, scammers everywhere! nakakahilo.

system change can be quite scary, for the unfamiliar and untested new system to take over can be more cutthroat than the previous with no guarantee of success. and we could be left holding the baby yet again, kasi if something goes wrong, the likes of cv et al, can just go overseas and watch from afar, leaving us all to bear the brunt and be bloodied yet again.

though, I like the new transport ticketing system, the ease of renewing passports, but renewing drivers license is summat a nightmare for some of us.

though I have long accepted that we cannot govern beyond election, new kings bring new practices ika. even other countries are the same, with new change of government, there is new regulations and sometimes, what has been regulated is made unregulated. like what trump is doing in united states.

“… but renewing drivers license is summat a nightmare for some of us.” – Kasambahay

I thought that was fixed decades ago?

we run out of plastic cards that people sometimes use e-license, kaso they lost or misplaced their phones so they end up with temporary remedy: a paper copy.

That is a nightmare?

That is a nightmare?

I’m surprised by Sen Kiko’s aggressiveness, and even Sen Bam’s to some extent. I don’t think the olds are done and I have no idea who capable young politicians might be. Young Sotto seems to lack patriotic zeal, similarly to Robredo.

Yes

With Leni not wanting to be president assumption.

If Risa becomes president, Bam, Kiko can be anchors to the floating young ones, not to sink them but just to keep.their feet grounded. ( messy metaphors)

Anchors, yes, the wise old farts, lol.

lol

What is lacking.

1) Political cohesiveness and ability to organize liberal/leftist/business groups, secure funding, etc.

2) Patriotic zeal, or whatever you would call the gap between Leni Robredo’s passivity and the peoples’ calling for her to lead.

3) Education about competence, honesty, and patriotic voting among the general public.

4) Laws that would convert dynastic fiefs to civic governments.

5) A capable justice system: policing, investigations, and courts.

In terms of the Filipino psyche what is lacking is a knowledge of success, a relatability to achievement, and the ability to conceptualize an optimistic future that can be used to guide today’s decisions. Oppression is oppressive.

“In terms of the Filipino psyche what is lacking is a knowledge of success, a relatability to achievement, and the ability to conceptualize an optimistic future that can be used to guide today’s decisions. Oppression is oppressive.” – JoeAm

Are you talking about leadership, or the people, or both?

Hmm, good question. I was talking about voters but it does apply to leaders as well. The corrupt do seem optimistic however.

Your question was addressed below and comments in the previous article.

The Philippines does not lack intelligence, plans, or governance tools. It suffers from an emphasis on representations of action rather than action itself. Cultural reform programs, public consultations, opinion surveys, balanced scorecards, and strategy maps are often treated as engines of change, but in practice they function largely as optics—creating the appearance of control while insulating decision-makers from responsibility.

Accountability frequently follows two familiar scripts: assigning blame to a single “mastermind” or conducting broad investigations to demonstrate activity. Both are politically convenient but largely ineffective: the former punishes individuals while systemic factors persist, and the latter creates visible action without addressing underlying issues. Corruption survives as an ecosystem, sustained by weak oversight, discretionary power, and low political costs for abuse.

Efforts to reform culture in abstraction—shaping values, perfecting frameworks, and designing processes before acting—often reverse causality. Culture emerges from repeated execution, visible results, and consequences for inaction. Governance is constrained by procedural defensibility, rewarding compliance over outcomes, and producing “learned helplessness,” where initiative and problem-solving atrophy. System change is therefore risky: reforms may improve some services while leaving others inefficient, and failures are socialized while elites escape consequences.

This dynamic is reflected in Filipino behavior. Filipinos are often described as timid and compliant—yet also undisciplined and pasaway. This is context-driven, not character-driven. Abroad, in Singapore or Saudi Arabia, Filipinos follow rules meticulously because enforcement is consistent and consequences are real. At home, laws are vague, enforcement selective, and penalties negotiable. Rule-breaking is rational where the system rewards circumvention. Discipline, therefore, is institutional, not cultural.

Breaking this cycle requires enforced execution: small, concrete actions tied to measurable outcomes, reviewed iteratively, with consequences for non-performance. Coupled with transparent procurement, real-time audits, whistleblower protection, and independent oversight, this approach strengthens institutions and reduces opportunities for abuse. Until action replaces illusion as the primary metric of governance, the Philippines will continue to govern effectively on paper but ineffectively in reality.

The Philippines has the technical knowledge, successful pilots, and expert blueprints to solve its development challenges, yet implementation consistently fails—not for lack of ideas, but because political will is the elephant in the room. Fragmented authority, discretionary power without accountability, short-term political incentives, and weak execution structures leave even sound plans gathering dust while citizens bear the costs. The country’s deficits are clear: reformist and liberal political groups lack cohesion, organizational capacity, and funding; leadership often fails to match public calls for decisive, patriotic action; the electorate remains under-educated about competence, integrity, and national interest in voting; dynastic fiefdoms dominate local governance; and the justice system—policing, investigation, courts—remains incapable of enforcing accountability. Closing these gaps requires binding national standards, alignment of authority with accountability, multi-administration planning, and protections for vulnerable stakeholders, all enforced through a disciplined Performance-Implementation-Results (PIR) cycle. Execution, not culture or additional plans, drives compliance; visible results build trust, discipline, and societal buy-in. The question is no longer what to do—the knowledge exists—but whether the political system has the courage to constrain its own discretion and turn plans into action.

FWIW

https://tribune.net.ph/2026/01/02/mass-shelter-boom-seen-with-new-ceiling

Mass shelter boom seen with new ceiling

The new price ceiling is reflective of the current increases in the prices of land, labor and materials, and will ensure support for the production of socialized housing, both vertical and horizontal projects.

On topic tv sitcom return.

https://www.abs-cbn.com/entertainment/showbiz/movies-series/2026/1/2/-home-along-da-riles-returning-in-2026-1525

Recomnended Reading.

https://books.google.com.ph/books/about/Five_Hundred_Years_Without_Love.html?id=BZ39zQEACAAJ&redir_esc=y

Title: Five Hundred Years Without LoveAuthor: Alexander L. LacsonGenre: Fiction (Philippine social/political novel)Pages: ~368 pagesPublished: 2020 (also listed 2021 edition)ISBN: 9791220105965

📖 What the Story Is AboutFive Hundred Years Without Love is a novel that blends personal drama with social commentary. The plot centers on Anton Hinirang, a man who has spent decades unable to move on from his first love, Marian, whose parents forced her into a marriage for wealth and status. Even as Anton becomes successful, he remains unhappy until a series of family tragedies—linked to systemic societal problems in the Philippines—push him toward a deeper understanding of himself, his life’s purpose, and ultimately, a reunion with his true love.

At its core, the book explores:Love and personal fulfillment

The effects of societal “social cancer”—like greed, selfishness, and inequality—on individuals and familiesHow the absence of love in hearts (especially leaders) contributes to poverty, injustice, and widespread suffering

📌 Themes & ConceptsAuthors and critics describe the novel as:A reflection on Filipino society, drawing parallels to historical and contemporary social ills, similar in spirit to José Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere in its critique of societal problems.

A call to love, compassion, and reform—arguing that societal change begins with the transformation of hearts and leadership.

A story of hope, with the latter parts of the book presenting a vision called “A Dream Philippines”, outlining possible reforms and paths toward national improvement.

That fits like a glove to my comment about oppression being oppressive.

I follow and noticed you comment about it every now and then.

Actually CV also expressed this through works of Rizal.

Yes.

More related news.

https://gulfnews.com/world/asia/philippines/philippines-unlocks-99-year-land-leases-for-foreigners-is-now-the-time-to-cash-in-on-ph-economic-boom-1.500396287

Fake birth certificates of the likes of Guo will be a thing of the past.

we risk having a state within a state like what indonesia is currently experiencing with the chinese 99yrs lease of morowali nickel hub. indonesia doesnt not allow raw minerals export, kaya the chinese circumvented and leased the hub, built an airport, processed the raw nickel and exported the end product to china. and indonesian authorities has no say on the matter, they can no longer access the hub once it entered into new lease agreement. indonesian customs cannot supervise what comes in and out of the airport. there was even suspicion the airport may have been used for illegal activities like smuggling of firearms, drugs and cigarettes, etc. kaya, feeling threatened, the indonesian president probowo subianto countered by immediately signing military treaty with australia. and that made china quite unhappy.

with philippines, I wonder how will we be able to control or have a say on the leasehold. coz if china is lessee, they will proverbially changed locks and we shall be denied access too.

Thanks for the good examples.

https://mb.com.ph/2026/01/02/a-complete-district-grows-beyond-the-metro

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jan/17/seoul-cheonggyecheon-motorway-turned-into-a-stream?utm_source=chatgpt.com

https://www.dailyclimate.org/cities-embrace-nature-by-removing-concrete-for-greener-spaces-2667365432.html

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20240222-depaving-the-cities-replacing-concrete-with-earth-and-plants