Philippines at Sea: How the National Maritime Council and Blue Economy Bills Can Transform Our Oceans

By Karl Garcia

The Philippines is a nation defined by its waters. As an archipelagic state with thousands of islands, our seas are more than just borders—they are the backbone of our economy, the source of livelihoods for millions of fishermen, and the arena where our sovereignty is tested. Yet, for all their importance, our maritime governance has long been fragmented. More than two dozen agencies share overlapping responsibilities for security, fisheries, environmental protection, and shipping, leading to duplication, inefficiency, and weak enforcement.

In 2024, the government took a bold step with Executive Order 57, establishing the National Maritime Council (NMC). The NMC is designed to coordinate these diverse agencies, implement the Philippine Maritime Zones Act (PMZA) and the Archipelagic Sea Lanes Act (ASLA), and ensure that maritime security, resource management, and foreign policy are aligned under one institutional roof.

But there’s a catch. EO 57 provides a strong framework, yet the NMC lacks key powers: it cannot directly control budgets, command operational units, or override agency heads. Information remains siloed, enforcement resources are stretched thin, and political factionalism often slows decision-making. Without reforms, the Council risks becoming another committee that produces reports but cannot enforce them at sea.

Enter the Blue Economy Bills

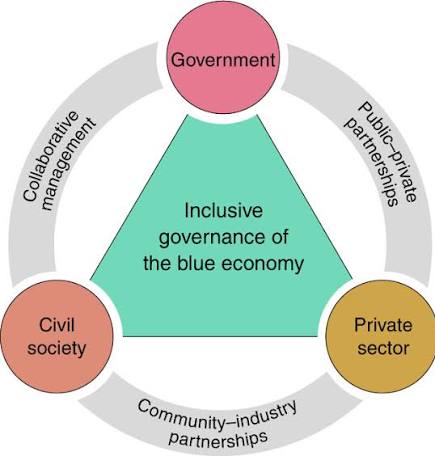

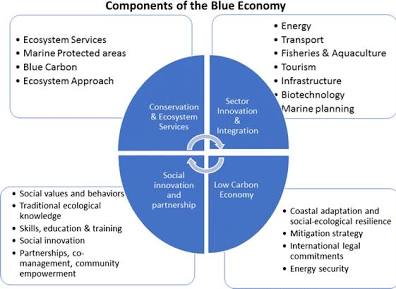

While the NMC addresses coordination, the Blue Economy Bills (Senate Bill 2450 / House Bill 9662) focus on sustainable use of our marine and coastal resources. These bills aim to:

Make the ocean a driver of economic growth, not just a source of fish or energy.

Promote marine spatial planning, ocean accounting, and sustainable infrastructure.

Introduce “blue finance” mechanisms, like blue bonds, to fund projects that support fisheries, renewable energy, and coastal resilience.

Protect ecosystems while creating jobs for coastal communities.

In short, the Blue Economy bills give a purpose and financing strategy to the NMC’s operational plans. Together, EO 57 and the Blue Economy framework can transform our maritime governance from fragmented to integrated, sustainable, and strategic.

Why This Matters Now

- Sovereignty and Security

Our maritime zones, especially the West Philippine Sea, are contested. Coordinated governance ensures that legal rights under UNCLOS and the 2016 Arbitral Award are matched by actual enforcement capability. - Sustainable Growth

Marine resources are finite. Overfishing, pollution, and unplanned development threaten both biodiversity and livelihoods. A blue economy approach ensures we protect our seas while generating economic value. - Data and Decision-Making

The NMC can establish a Maritime Fusion Center—a hub where data from radar, satellites, fisheries monitoring, and ports come together. This shared situational awareness allows smarter, faster decisions. - Local Empowerment

Coastal communities benefit directly through sustainable fisheries, eco-tourism, and renewable energy projects, ensuring that local voices are integrated into national maritime strategy. - Long-Term Resilience

With the Blue Economy Bill and the NMC working together, maritime governance becomes institutionally permanent, less dependent on political cycles or shifting presidential priorities.

Challenges Ahead

Of course, the path is not without obstacles:

Bureaucratic turf wars between agencies like the Coast Guard, Navy, and BFAR.

Resource constraints: patrol vessels, aircraft, and funding for environmental enforcement remain limited.

Political risks: maritime decisions can be exploited by political factions or foreign pressures.

Data integration: merging agency data into a single operational picture will require investment and coordination.

Even so, these challenges are surmountable if the NMC is empowered with budget authority, clear operational hierarchies, and legislative backing, while the Blue Economy Bill ensures sustainable financing and development.

A Strategic Opportunity

The combination of the NMC and the Blue Economy Bill is historic. For the first time, the Philippines has a chance to manage its maritime domain holistically—linking security, sustainability, and economic opportunity in one coordinated framework.

Imagine a scenario where patrols protect our territorial waters, marine spatial planning prevents overfishing, renewable energy projects create jobs for coastal communities, and our ocean resources generate long-term revenue through blue finance. This is not just policy theory—it is achievable if we act now.

The choice is clear: invest in the NMC, pass the Blue Economy Bill, and commit to sustainable, sovereign, and inclusive maritime governance—or continue with fragmented policies that leave our oceans underprotected and our national potential untapped.

Our seas are calling. It’s time we answer.

_________________________________________________

Cover photo from SHIPA Freight article “5 Largest Ports in Philippines“.

Some backgrounders

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philippine_Maritime_Zones_Act?wprov=sfla1

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Philippine_Archipelagic_Sea_Lanes_Act

PIDS study on the Blue Economy

https://www.pids.gov.ph/details/news/in-the-news/ph-has-vast-potential-for-blue-economy

I find this article uplifting, Karl, as if the Philippines is finally realizing its character and potential strengths. We’ve written a lot about that here at TSOH. I hope the initiatives become an example of and an inspiration for a first world Philippines.

Thank you Joe, I believe and hope so that we will be first world one day.

Odd to say it, but I believe President Marcos is leading in that direction.

It is ok four years ago, I could never had imagined that.

I haven’t followed this legislation that closely, but it would be important to have consistent, strong, and sustained government support if it does pass. Otherwise it will end up becoming another aspirational messaging law that never has any permanent and tangible effect. If it were me, I would have approached it in a more pragmatic and piecemeal but targeted way that provide real and immediate effects. Small wins are easier to build up into bigger overall successes. Big failures can cause long lasting discouragement. Later legislation can connect what needs to be connected and smooth what needs to be smoothed over. Maybe it’s just me but I have found that in life when one makes goals so expansive, one will quickly become overwhelmed and most will just give up halfway through.

I guess passing the Philippine Maritime Zones Act togetger with the Archipelagic Sea Lanes Act woyld count as a small win.

Mocked by the rule breaker China who created new laws not in line and in syncewith Unclos which they signed and acts as if they did not.

The new dmestic laws codifies what Unclos sad.

Small wins indeed.

Another small win will be the Blue Economy Act.

China has passed several maritime regulations that are considered by many countries and legal experts to be out of line with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), primarily the China Coast Guard Law (CCGL) of 2021 and its associated Administrative Law Enforcement Procedures (Order No. 3) which came into effect in June 2024.

The key aspects of these laws that conflict with UNCLOS are:

These laws are widely seen by other nations, including the United States, Japan, and the Philippines, as an attempt to use domestic legislation to legitimize China’s expansive and legally contested maritime claims in the South China Sea, thereby escalating regional tensions.

Yes, China has signed and ratified UNCLOS (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea). It participated in the negotiation of the convention from 1973 to 1982 and ratified it in 1996.

However, China’s actions and interpretations of the convention in the South China Sea have been a source of significant international dispute:

This creates a complex situation where China is a party to the convention but selectively applies or interprets its provisions, particularly concerning the South China Sea disputes.

A tad scary. I wonder how they will respond to US sail-throughs or the Philippine Coast Guard patrolling Philippine Seas that China claims. Cases need to be filed in international courts, for example, the Philippines suing China for damages to Scarborough Shoal. Or to have China’s new rules invalidated within Philippine seas.

If they continue to violate International law while claiming they are not violating, the world needs to react.

there’s another way, not tru’ international courts. recall how china’s president xi spoke to trump for trump to reign in its ally the new japanese prime minister takaichi when takaichi declared that japan may sell arms to taiwan if china invades taiwan!

president xi was incensed, livid that japan is flexing military muscles. and now, takaichi is being summoned to the white house to see trump.

we should do likewise, talk to trump and tell trump to talk to president xi, telling xi to reign in chinese coastguard and its highly dangerous activities in the west phil sea.

trump wants to be supreme deal maker/peace maker. if he can deal and curb china’s illegal maritime activities in the contested water, trump might just get his much longed for nobel peace prize award next time round.

Trump wants to be Xi’s equal and would not talk to Xi on the Philippine’s behalf. He is more likely to give the Philippines to China if Xi sends money to his bank account. He has no nationalistic principles whatsoever.

The Trump administration will be gone in three years time. Every new comer administration may have foreign policies that may differ from the previous one. But certainly, the US will not allow some sort of toll fees in the disputed waterways, IMHO.

Trump has turned America into an enemy state of Europe. He has no nationalistic view, only a personal one. It’s a very ugly nation right now, warring on Americans and murdering Venezuelans, throwing Ukraine under the Russian bus. The Supreme Court is corrupt, the Legislature demolished as caretakers of American well-being, Constitutional protections are being undermined. I cannot express how horrible this is. America, a noble but now ruined idea of freedom and fairness, descended into hate. Ugly.

so far, 1st female prime minister of japan seems to have some steely kahones! trump did not stop her from lighting china’s fuse altogether, only told her to turn down her tone a bit. is all.

shame, the leader of the world’s greatest nation is summat neutered, there was opportunity for leader to tit for tat with xi, that leader would talk to takaichi only if xi will talk to his coastguards and tell them to tone down their aggressiveness in the contested water.

the phillippines is just incidental, the main reason for tit for tat would have been to keep navigational sea routes open for all shipping lines in the area. not for china to hog all the sea lanes only for themselves.

Yes, the Japanese PM talks directly. China is different, she says. They don’t play by our norms, even within China. I like her a lot. As I understand it, the US will not let China move past a line drawn through Japan and the Philippines and further south. Taiwan is on the US side of the line. So I think the Philippines will become very militarized with assistance from the US and Japan. I view that as good.

China is turning the tables on Japan saying that Japan is threatenibg them with self defense.

The

Philippines‘ “blue economy” reached PHP 1.01 trillion in 2024, or approximately 3.8% of its GDP, and holds significant potential for further growth. The blue economy broadly encompasses the sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth while improving livelihoods and ensuring the health of marine ecosystems.

The Philippine Blue Economy at a Glance

In 2024, ocean-based industries in the Philippines were valued at over a trillion pesos. The broader global ocean economy is a multi-trillion dollar sector, underscoring the immense potential for the Philippines to further harness its vast marine resources in a sustainable manner.

Key sectors within the Philippine blue economy include:

Benefits to the Philippines

Harnessing the blue economy offers numerous benefits to the Philippines:

The Philippine government is actively developing an integrated strategy through legislative proposals and the potential establishment of a Blue Economy Council to maximize these benefits while safeguarding its marine heritage.

I like that term, “blue economy”. It makes it possible to seek ways to elevate the sector. This is excellent.

Everything is possible.

OT: sharing a new MLQ3 article:

ahem, may still be lame duck, maybe lamest duck in existence!

you know what’s the downside with of all those bills supported by president marcos et al? them bills did come with their own IRRs, immediately applicable across the board: as of today, dated and signed. wala sa codicil. missing in action like bato de la rosa.

good thing though that the president said, he no longer panic when troubles come surging at him: he’ll just turn around and fire people from their jobs!

https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/money/economy/969200/adb-approves-500-m-loan-for-ph-blue-economy-development/story/

Off topic. Hope the lower house gets this done and the senate to act on it asap.

https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/2153470/house-panel-approves-long-delayed-national-land-use-act

How South China Sea Disputes Impede the Philippines’ Blue Economy Potential

The South China Sea (SCS) disputes significantly undermine the Philippines’ ability to develop a robust blue economy, limiting opportunities in food security, energy development, sustainable industry, and maritime governance. Persistent tensions with China—particularly in areas within the Philippines’ Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ)—create geopolitical, environmental, and economic constraints that directly affect communities and national development goals.1. Fisheries Sector Disruptions

Access to traditional fishing grounds—especially Scarborough Shoal (Panatag) and areas within the Kalayaan Island Group—is increasingly restricted due to the presence of Chinese militia, coast guard, and commercial vessels. Filipino fisherfolk routinely face:

Given that millions of Filipinos depend on fisheries for livelihood and protein intake, this undermines both food security and poverty alleviation in coastal communities.2. Energy Security Challenges

The West Philippine Sea contains significant hydrocarbon deposits, including natural gas in the Reed Bank. However:

Without stable access to its EEZ resources, the Philippines faces long-term constraints in reaching energy independence and transitioning to renewable offshore energy systems.3. Investment and Trade Uncertainty

Geopolitical risks deter investment in sectors vital to the blue economy:

This instability raises risk premiums and slows capital inflows necessary for sustainable coastal development.4. Environmental Degradation and Unsustainable Practices

The disputes contribute to unregulated marine exploitation:

These environmental impacts erode the very foundation of a sustainable blue economy, which depends on healthy marine ecosystems to support fisheries, tourism, and coastal protection.5. Sovereignty and Governance Limitations

The conflict highlights systemic weaknesses in the Philippines’ maritime governance:

This governance fragmentation hampers the country’s ability to manage, protect, and sustainably use its marine resources—core pillars of a blue economy.Conclusion: A Strategic Constraint on National Development

In essence, the South China Sea disputes impose severe geopolitical, environmental, and economic constraints that prevent the Philippines from optimizing its marine wealth. These tensions:

Fully realizing the Philippines’ blue economy potential requires not only diplomatic and legal strategies, but also strengthened maritime governance, interagency coordination, ecological protection, and resilient coastal development policies.

This should be the basis of legal action against China.

MANILA — Retired Supreme Court Senior Associate Justice Antonio Carpio on Monday urged Filipinos not to confuse patriotism with economic retaliation, explaining that the Philippines has no policy for a boycott of Chinese products despite escalating tensions in the West Philippine Sea.Speaking to reporters on the sidelines of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) Reservists National Convention in Makati City, Carpio emphasized that while the maritime row remains serious, the situation does not require wartime actions.“There is no prohibition. We are not at war with China. We have diplomatic relations with China. Its dispute should be resolved in accordance with international law,” Carpio said.“We are not at war; we have a dispute. But it doesn’t mean that if we have a dispute, we do not talk to them or do trade with them. It doesn’t follow. We are not at a stage where there is embargo of goods from other side. We have diplomatic relations,” he continued.

true, we are not at war, we were just heavily water cannoned, our ships nearly capsized, with few mariners physically hurt, one lost a finger. strong laser beams pointed at out pilots, nearly blinding them and causing them accident in the sky.

our resupply missions to ayungin shoal were harassed, chased, and threatened, our fisherfolks not allowed to fish in our eez, or marine resources like coral reefs pulverized, our carefully tended giant clams killed, their shells harvested to be made into mother of pearl buttons all for china’s glory. so of course we are not at war!

True. The Philippines will also arm to the teeth with the assistance of the US.

China has set up an electronic Kill zone in the WPS

https://asiatimes.com/2025/12/china-builds-an-electromagnetic-kill-zone-in-the-south-china-sea/

Philippine-U.S. Defense Framework: Legal Obligations and Political Control Executive Summary

The Philippines-U.S. security relationship operates through a carefully calibrated framework that creates military options while preserving Philippine sovereignty. The 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty (MDT) establishes consultation-based mutual defense obligations, the 2014 Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) enables rotational U.S. presence without permanent basing, and emerging trilateral cooperation with Japan strengthens regional coordination without creating new binding commitments. Crucially, this architecture maintains strategic ambiguity: it complicates adversary planning while allowing Manila to retain ultimate political control over the use of its territory in contingencies. I. The Mutual Defense Treaty: Consultation, Not Automaticity Legal Framework

The 1951 MDT creates a mutual defense obligation if an armed attack occurs in the Pacific area against either party. However, the treaty’s language emphasizes consultation and coordinated response rather than automatic military intervention.

Key provisions require parties to:

Operational Reality

The treaty creates legal space for political decision-making about what constitutes an “attack” requiring collective action. Historical precedent from the Korean War and Cold War era demonstrates that MDT responses are shaped by political context rather than operating as formulaic triggers. Critical Ambiguities

Geographic scope: The “Pacific area” language allows for political interpretation during crises. Whether attacks on Taiwan or U.S. forces in the broader region trigger MDT obligations remains deliberately unclear.

Definition of “attack”: The threshold for what constitutes an armed attack requiring mutual defense response is not precisely defined, creating room for political judgment. II. EDCA: Enabling Framework with Political Controls What EDCA Enables

The Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement, revived and expanded in 2023, authorizes:

What EDCA Does Not Create

No U.S. sovereignty: EDCA sites are not permanent U.S. bases in legal terms. They remain Philippine territory.

No automatic wartime transfer: The agreement does not create automatic command relationships or unilateral rights for the U.S. to conduct operations.

No offensive operations carte blanche: U.S. forces cannot launch offensive operations from Philippine soil without Manila’s explicit consent. Political Control Measures (PCMs)

The critical operational constraint lies in Political Control Measures—domestic authorizations, rules of engagement, and approval procedures that the Philippines imposes to control facility usage in contingencies. These PCMs are:

President Marcos Jr.’s repeated statement that the Philippines “will not be used as a staging post” represents a key public PCM, signaling Manila’s intent to retain strict operational control while managing domestic political sensitivities and signaling restraint to Beijing. III. Trilateral Cooperation: Political Coordination Without New Legal Obligations U.S.-Japan-Philippines Framework

Recent trilateral summits and ministerial communiqués have formalized cooperative activities including:

Scope and Limitations

What trilateral arrangements achieve: Strengthened interoperability and political alignment among three democracies sharing regional security concerns.

What they do not achieve:

Trilateral declarations increase political pressure and coordination options without changing underlying legal commitments. They raise escalation stakes through enhanced logistics and surveillance capabilities while maintaining each nation’s decision-making sovereignty. IV. Strategic Geography: The 2023 EDCA Expansions

The 2023 expansion of EDCA sites to include locations in northern Luzon and Palawan significantly enhances Philippine strategic relevance to:

However, this geographic positioning simultaneously:

V. Key Decision Points and Indicators Internal Implementation

Watch for: Parliamentary or executive instruments, defense-to-defense memoranda, or joint defense agreements defining crisis-use parameters for EDCA facilities. While likely classified, policy papers or leaks often signal their contours. Operational Integration

Watch for:

These steps raise baseline integration without changing legal triggers. Political Signals

Watch for:

Historical precedent shows local officials have protested when EDCA sites were announced, indicating potential friction points in crisis implementation. VI. Strategic Assessment The Ambiguity Framework

The Philippine-U.S. defense architecture deliberately maintains ambiguous deterrence. This serves multiple strategic purposes:

For the United States: Creates options and access for regional contingencies while sharing political risk with a sovereign ally.

For the Philippines: Gains security guarantees and military modernization support while preserving sovereign control and domestic political legitimacy.

For regional stability: Complicates adversary planning and raises costs of aggression without automatic escalation triggers. The Political Control Dynamic

The framework’s effectiveness depends on Manila’s willingness to activate its enabling provisions during crises. Key factors influencing this decision include:

Sovereign Discretion as Strategic Asset

Manila’s retention of political control over EDCA facility usage is not a weakness but a strategic feature. It allows the Philippines to:

VII. Scenario Implications Direct Attack on Philippine Territory

MDT consultation obligations are strongest and most likely to result in U.S. military response. EDCA facilities would likely be fully activated with minimal political friction. Taiwan Contingency

MDT triggers remain ambiguous and subject to political interpretation. EDCA facility usage would require explicit Philippine government decisions, with PCMs playing a critical role. Trilateral coordination would enhance logistics and intelligence sharing but not create automatic commitments. South China Sea Gray Zone Operations

Falls below MDT thresholds for armed attack. Philippine decisions on EDCA facility usage would depend heavily on escalation risk assessment and domestic political calculations. U.S. and Japanese coordination would focus on surveillance, logistics, and political signaling rather than combat operations. VIII. Conclusions

The Philippine-U.S. security relationship represents a sophisticated balance of legal enablement and political control. The MDT provides consultation-based mutual defense commitments, EDCA creates physical infrastructure and access for military cooperation, and trilateral arrangements enhance coordination—all while preserving Manila’s sovereign decision-making authority.

This architecture reflects both nations’ strategic interests: the United States gains access and options for regional contingencies, while the Philippines secures defense guarantees and military modernization without surrendering sovereignty or automatically committing to conflicts beyond its direct interests.

The framework’s ultimate effectiveness will be tested not by its legal provisions but by political will during crises. Manila’s decisions to activate EDCA facilities and interpret MDT obligations will depend on specific contingency circumstances, domestic political dynamics, and strategic calculations about escalation risks and national interests.

Key takeaway: Legal frameworks create possibilities; political decisions determine realities. The Philippine-U.S. defense relationship provides robust enabling mechanisms while deliberately preserving the ambiguity and sovereign discretion that both allies consider essential to effective deterrence and crisis management. Appendix: Research Priorities

For analysts monitoring this relationship, priority indicators include:

These indicators provide early warning of changes in operational readiness, political will, or strategic alignment that may affect framework implementation during crises.

Good description of the factors involved. As for Marcos saying the PH will not be a staging ground for the US, I think in fact the nation will become a staging ground under Philippine sovereign rights and best interests. Military might is building and will continue to build. At some point AFP will have to expand its number of troops supporting the effort, and a lot of AFP will become high-skill, that is, jet pilots, warship captains and crew, missile operators, drone operators, logistics pros, training pros, radar operators, and more.

# Regional Security Coordination in the Western Pacific: An Analysis of Japan-Philippines Defense Cooperation and Taiwan Contingency Planning

## Executive Summary

This white paper examines the evolving security coordination between Japan and the Philippines in the context of regional stability and Taiwan contingency planning during 2024-2025. Drawing on official government statements, defense ministry documentation, and verified reporting from established news agencies, this analysis explores three interconnected developments: Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s October-November 2025 parliamentary remarks on Taiwan, Philippine military contingency planning for overseas workers, and the deepening Japan-Philippines defense partnership formalized through the Reciprocal Access Agreement.

The paper demonstrates that while these developments represent significant shifts in regional security architecture, they reflect domestic policy considerations and bilateral cooperation rather than coordinated interventionist planning. Japan’s evolving security posture remains bounded by constitutional constraints and diplomatic caution, while Philippine planning focuses on citizen protection rather than military involvement. The trilateral framework involving the United States serves primarily to enhance coordination and interoperability rather than establish collective defense commitments regarding Taiwan.

## 1. Introduction

### 1.1 Context and Significance

The security environment in the Western Pacific has undergone substantial transformation since 2020, driven by evolving great power dynamics, technological military modernization, and changing threat perceptions among regional actors. The Taiwan Strait remains a focal point of strategic concern, with multiple nations developing contingency frameworks to address potential scenarios ranging from economic disruption to military conflict.

This white paper analyzes recent developments in Japan-Philippines security cooperation, with particular attention to how both nations are approaching Taiwan-related contingencies. The analysis period covers late 2024 through late 2025, a timeframe marked by significant policy statements, bilateral agreements, and public discussion of previously sensitive security topics.

### 1.2 Methodology and Sources

This analysis relies on primary sources including official government statements, defense ministry publications, and parliamentary records from Japan and the Philippines. Secondary analysis draws from established news agencies with verified reporting standards, including Kyodo News, Reuters, Philippine News Agency, and specialized publications such as The Diplomat and assessments from the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

The paper distinguishes carefully between verified official positions, contingency planning discussions, and speculative analysis, noting where uncertainty exists in public reporting.

## 2. Japan’s Evolving Position on Taiwan Security

### 2.1 Prime Minister Takaichi’s Parliamentary Statements

In October-November 2025, Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi made remarks during parliamentary proceedings that attracted significant attention regarding Japan’s stance on Taiwan security. According to Kyodo News reporting on these sessions, Takaichi discussed scenarios in which developments affecting Taiwan could be characterized as threats to Japan’s national survival under the framework established by Japan’s 2015 security legislation.

The 2015 legislation allows Japan to exercise collective self-defense rights under narrowly defined circumstances when an armed attack against a close ally poses a “clear danger” to Japan’s survival and when no other means exist to repel the attack and protect Japanese citizens. Takaichi’s remarks explored whether certain Taiwan scenarios might meet these criteria, representing a more explicit discussion of Taiwan contingencies than previous Japanese leaders had provided publicly.

### 2.2 Clarifications and Constitutional Boundaries

Following media coverage and regional reaction to her initial remarks, Takaichi provided clarifications emphasizing the hypothetical nature of her statements. According to Kyodo News coverage, she stressed that Japan maintains its long-standing position on Taiwan, which recognizes the People’s Republic of China as the sole legal government of China while maintaining practical relations with Taiwan through unofficial channels.

The Diplomat’s analysis of these statements places them within the context of Japan’s constitutional constraints on the use of force and the practical application of the 2015 security legislation. Japan’s post-war constitution, particularly Article 9, prohibits the nation from maintaining war potential or using force as a means of settling international disputes. The 2015 legislation represents a reinterpretation rather than amendment of these constraints, allowing limited collective self-defense while maintaining fundamental pacifist principles.

### 2.3 Policy Continuity and Evolution

Despite the attention generated by Takaichi’s remarks, Japanese policy toward Taiwan shows more continuity than rupture with previous positions. Japan has progressively elevated Taiwan’s security significance in official documents since 2021, with joint statements alongside the United States referencing “peace and stability” in the Taiwan Strait as essential to regional security.

Takaichi’s statements represent an evolution in the explicitness with which Japanese leaders discuss Taiwan scenarios publicly, but they do not constitute a fundamental policy shift toward recognizing Taiwan independence or committing to its defense. The emphasis on hypothetical scenarios and the repeated invocation of constitutional and legislative frameworks indicates Japan’s continued caution in managing the tension between growing security concerns and diplomatic constraints.

## 3. Philippine Contingency Planning for Taiwan Scenarios

### 3.1 Overseas Worker Protection Focus

The Philippines maintains one of the world’s largest populations of overseas workers, with significant numbers employed in Taiwan, mainland China, Hong Kong, and throughout the Asia-Pacific region. Philippine government sources, as reported by the Philippine News Agency, indicate that approximately 150,000-200,000 Filipino workers reside in Taiwan at any given time, employed primarily in manufacturing, caregiving, and domestic work sectors.

During late 2024 and 2025, Philippine military and foreign affairs officials made public statements acknowledging contingency planning efforts focused on potential evacuation and protection of Filipino citizens in Taiwan should regional tensions escalate. These statements, covered extensively by Philippine News Agency and Reuters, emphasized the protective rather than interventionist nature of such planning.

### 3.2 Independent Planning Framework

Philippine officials have been explicit in clarifying that contingency planning regarding Taiwan is driven by domestic responsibilities for citizen protection rather than coordination with external powers’ military planning. Reuters reporting on statements by Philippine defense officials emphasized that evacuation planning represents standard consular and military preparedness rather than alignment with any particular position on Taiwan’s political status.

The emphasis on independent planning serves multiple purposes in Philippine diplomacy. It allows the Philippines to maintain productive relations with both the United States and China while fulfilling domestic responsibilities for overseas worker protection. It also helps manage domestic political sensitivity regarding potential Filipino casualties in external conflicts.

### 3.3 Practical Planning Considerations

Contingency planning for potential Taiwan evacuations presents substantial logistical challenges given the numbers of Filipino workers involved and the limited maritime and air transport assets available to Philippine authorities. Philippine military statements, as reported by ABS-CBN News, acknowledge that large-scale evacuation scenarios would require substantial coordination with commercial shipping and aviation sectors, cooperation with Taiwan authorities, and potentially international assistance depending on the circumstances precipitating evacuation needs.

Planning scenarios reportedly include a range of circumstances from economic disruption requiring voluntary repatriation to rapid evacuation under threat conditions. The Philippine government’s experience with previous evacuation operations, including from Libya in 2011 and from conflict zones in the Middle East, provides operational templates but also highlights resource limitations that would be magnified by the scale of potential Taiwan operations.

## 4. Japan-Philippines Defense Cooperation Framework

### 4.1 Reciprocal Access Agreement

The centerpiece of recent Japan-Philippines defense cooperation is the Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA) signed in 2024, which according to Japan Ministry of Defense documentation establishes frameworks for simplified procedures when military forces from one nation operate in the other’s territory for training, exercises, and disaster response operations.

The RAA represents only the second such agreement Japan has concluded, following a similar arrangement with Australia. For the Philippines, it represents part of a broader strategy of deepening security partnerships with multiple regional actors while maintaining its long-standing treaty alliance with the United States.

The agreement’s practical provisions address logistics, legal status of forces, and coordination procedures. It does not create mutual defense obligations or commit either party to specific contingency operations, but it does facilitate more regular and complex joint activities that can enhance interoperability and coordination capabilities.

### 4.2 Defense Assistance and Capacity Building

Beyond the procedural frameworks of the RAA, Japan has provided substantial defense assistance to the Philippines focusing on maritime domain awareness and surveillance capabilities. According to Japan Ministry of Defense documentation and ABS-CBN News reporting, this assistance has included:

– Coastal surveillance radar systems to enhance monitoring of Philippine maritime zones

– Air surveillance equipment and training for Philippine military personnel

– Maritime patrol vessel transfers to strengthen Philippine coast guard capabilities

– Joint training exercises focusing on humanitarian assistance, disaster response, and maritime security

This assistance aligns with Japanese security priorities emphasizing freedom of navigation and stability in critical sea lanes, while addressing Philippine needs for improved capability to monitor and respond to activities in its maritime zones, particularly in areas of the South China Sea where Philippine and Chinese claims overlap.

### 4.3 Limitations and Boundaries

Despite the deepening cooperation, significant limitations bound the Japan-Philippines defense relationship. Japan’s constitutional constraints on collective defense apply equally to the Philippines as to other partners. Neither the RAA nor other bilateral agreements create commitments for Japan to defend the Philippines in conflict scenarios, including those potentially involving Taiwan contingencies.

The Philippines, for its part, has emphasized that security cooperation with Japan complements rather than replaces its treaty alliance with the United States and does not represent alignment in potential Taiwan conflict scenarios. Philippine officials have been careful to frame cooperation in terms of capacity building and conventional security challenges rather than great power competition dynamics.

## 5. Trilateral Coordination: Japan-Philippines-United States

### 5.1 Trilateral Exercise Framework

The Japan-Philippines bilateral relationship exists within a broader trilateral framework that includes the United States, which maintains treaty alliances with both Japan and the Philippines. According to U.S. Department of Defense documentation, trilateral exercises and coordination mechanisms have expanded since 2023, building on earlier bilateral U.S.-Japan and U.S.-Philippines exercise programs.

These trilateral activities have focused primarily on maritime security, humanitarian assistance and disaster response, and interoperability development. They provide opportunities for forces from all three nations to practice coordination procedures and develop familiarity with each other’s operational approaches and capabilities.

### 5.2 Taiwan Contingency Coordination Questions

The extent to which trilateral coordination explicitly addresses Taiwan contingency scenarios remains unclear in public reporting. U.S. defense officials, as reported by Reuters and defense publications, have indicated that trilateral exercises enhance general readiness and coordination that could be relevant to various contingencies, but have generally avoided characterizing them as specifically Taiwan-focused.

Analysis from the International Institute for Strategic Studies suggests that while Taiwan contingencies are inevitably considered within U.S. planning for Western Pacific scenarios, the trilateral framework with Japan and the Philippines serves multiple purposes and addresses various potential security challenges beyond Taiwan-specific scenarios. These include maritime security challenges, potential humanitarian crises, and coordination for disaster response throughout the region.

### 5.3 Treaty Obligations and Limitations

The U.S.-Japan Security Treaty and the U.S.-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty create different obligations and have different operational implications. The U.S.-Japan treaty specifically commits the United States to respond to armed attacks against Japan or Japanese-administered territories, while the Philippines treaty’s geographic scope and specific application have been subject to varying interpretations and remain somewhat ambiguous regarding certain scenarios.

Importantly, neither treaty creates obligations between Japan and the Philippines to come to each other’s defense, nor do they clearly establish that either ally would be obligated to support the United States in Taiwan contingencies. This means that while trilateral coordination enhances capabilities and relationships, it does not constitute a collective defense arrangement regarding Taiwan.

## 6. Regional Reactions and Strategic Implications

### 6.1 Chinese Responses

Chinese government statements, as reported by Xinhua News Agency and other Chinese official media, have characterized the deepening Japan-Philippines security cooperation and discussions of Taiwan contingencies as interference in China’s internal affairs and destabilizing to regional peace. Chinese diplomatic and military officials have emphasized that Taiwan is an integral part of Chinese territory and that external powers should not involve themselves in what China characterizes as a domestic matter.

The intensity of Chinese reactions to Takaichi’s remarks and to joint exercises appears calibrated to discourage further development of coordination mechanisms that Beijing perceives as directed against Chinese interests. However, Chinese responses have remained primarily in diplomatic and rhetorical rather than military realms, suggesting Chinese assessment that current developments do not yet constitute immediate security threats.

### 6.2 Taiwan Perspectives

Taiwan authorities, according to reporting from Taiwan-based media outlets, have generally welcomed increased regional attention to Taiwan Strait security while carefully avoiding characterizations that might provoke Chinese reactions or imply Taiwan dependence on external support. Taiwan officials have emphasized self-defense capabilities and determination while expressing appreciation for regional concerns about peace and stability.

Taiwan’s position involves managing complex tensions between seeking international support for its security, avoiding provocations that might provide justification for Chinese action, and maintaining domestic confidence in Taiwan’s ability to manage its own defense and security relationships.

### 6.3 ASEAN and Regional Powers

Other Southeast Asian nations have generally maintained careful positions on Japan-Philippines security cooperation and Taiwan contingency discussions. Most ASEAN member states maintain diplomatic recognition of the People’s Republic of China and avoid taking positions on Taiwan’s political status, while many also have security concerns about Chinese military modernization and assertiveness in maritime disputes.

The response from Southeast Asian nations generally reflects their preference for avoiding being forced to choose sides in great power competition while maintaining freedom of action in managing their own security relationships and concerns. Nations like Vietnam, Singapore, and Indonesia have their own complex relationships with both China and external powers like the United States and Japan, making them cautious about endorsing frameworks that might constrain their diplomatic flexibility.

## 7. Assessment and Analysis

### 7.1 Coordination vs. Alliance Formation

The developments examined in this white paper represent enhanced coordination and dialogue rather than the formation of a collective defense alliance regarding Taiwan. Japan’s constitutional constraints, Philippine focus on citizen protection rather than military involvement, and the absence of mutual defense commitments between Japan and the Philippines all limit the extent to which current cooperation could translate into coordinated military action in Taiwan contingencies.

The deepening relationships do, however, create enhanced capabilities for information sharing, logistics coordination, and potentially humanitarian operations that could be relevant in various contingency scenarios. They also contribute to a broader regional security architecture in which multiple nations maintain closer coordination with each other and with the United States.

### 7.2 Domestic Drivers and Constraints

For both Japan and the Philippines, domestic political considerations significantly influence the development and limits of security cooperation. In Japan, public opinion remains substantially pacifist, and constitutional debates about security policy generate significant domestic political controversy. Prime Minister Takaichi’s ability to pursue more assertive security policies is constrained by these domestic factors as well as by coalition politics within Japan’s parliamentary system.

In the Philippines, public opinion regarding involvement in external conflicts is highly sensitive, particularly given the substantial numbers of Filipino overseas workers who could be affected by regional instability. Philippine leaders face domestic pressure to prioritize citizen protection and economic relationships over security alignment that might risk Filipino lives or economic interests.

### 7.3 Strategic Uncertainty and Future Trajectories

The trajectory of Japan-Philippines security cooperation and regional approaches to Taiwan contingency planning remains substantially uncertain and dependent on multiple variables including:

– Evolution of cross-Strait relations and Chinese policy toward Taiwan

– U.S. security commitments and capabilities in the Western Pacific

– Domestic political developments in Japan, the Philippines, Taiwan, and China

– Economic relationships and dependencies that constrain security policy options

– Technological developments affecting military capabilities and deterrence dynamics

Future developments could include either deepening coordination approaching collective defense arrangements or stagnation and retreat from current cooperation levels depending on how these variables evolve and interact.

## 8. Conclusions

The developments examined in this white paper demonstrate that Japan and the Philippines are engaging more explicitly with Taiwan contingency scenarios than in previous years, but within significant constraints that limit the extent of current coordination and potential future involvement in Taiwan-related conflicts.

Japan’s evolving security posture reflects genuine concerns about regional stability and specific scenarios in which Taiwan developments could threaten Japanese security interests, but remains bounded by constitutional constraints, diplomatic caution regarding China relations, and domestic political limitations on security policy.

Philippine contingency planning focuses appropriately on citizen protection responsibilities rather than military involvement in Taiwan scenarios, reflecting both humanitarian obligations and strategic caution about involvement in great power conflicts.

The deepening Japan-Philippines defense relationship, supported by the trilateral framework including the United States, enhances regional coordination capabilities and contributes to a more networked security architecture in the Western Pacific. However, it does not constitute a collective defense arrangement regarding Taiwan and should not be characterized as creating obligations for either nation to participate in Taiwan contingencies.

Understanding these developments requires distinguishing between enhanced coordination capabilities, explicit defense commitments, and actual operational intentions. Current evidence suggests significant movement in the first category, limited movement in the second, and substantial uncertainty regarding the third.

Regional security dynamics will continue evolving based on multiple actors’ choices and strategic circumstances. The frameworks examined in this paper provide enhanced capabilities for coordination if needed, but their ultimate significance will depend on future developments in cross-Strait relations, U.S. strategic posture, and the domestic politics of all nations involved.

—

This is much too long for me to digest. I think the Philippines and Japan will become close partners.

WHITE PAPERGrey-Zone Warfare and the Philippine Defense Posture: Strategic Assessment and Recommendations

Author: Karl GarciaDate: December 2025Classification: UnclassifiedEXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Contemporary conflict has evolved beyond traditional military confrontation into a continuous state of competition conducted primarily through non-military means. The People’s Republic of China’s assertive posture in the South China Sea—particularly in the West Philippine Sea—exemplifies this shift through systematic employment of grey-zone tactics designed to achieve territorial control without triggering armed conflict.

The Philippines’ Porcupine Defense strategy, while effective at deterring conventional military aggression, demonstrates critical vulnerabilities against incremental salami-slicing and cabbage encirclement tactics. This white paper analyzes the theoretical foundations of modern conflict, assesses Chinese grey-zone methodology, evaluates Philippine defensive capabilities, and proposes a comprehensive multi-layered response framework.

Key Findings:

Primary Recommendation: The Philippines must evolve from a purely deterrent posture to an integrated Grey-Zone Defense System combining military deterrence with persistent civilian presence, non-lethal response capabilities, and institutionalized allied coordination.I. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK: THE CONVERGENCE OF CONFLICT THEORY1.1 The Evolution of War

Contemporary conflict represents not a departure from classical military theory but rather the simultaneous application of all historical conflict paradigms. Understanding this requires synthesizing insights from multiple strategic thinkers:Clausewitzian Foundation

Carl von Clausewitz established that war is the continuation of politics by other means. This foundational principle remains valid—what has changed is the proportion of military versus non-military instruments employed in political competition.Gerasimov Observation

General Valery Gerasimov’s 2013 article noted that the ratio of non-military to military measures in modern conflict is approximately 4:1. This represents not a new Russian doctrine but an observation about how all modern states conduct strategic competition through:

Smith’s “War Amongst the People”

General Rupert Smith identified that industrial-age decisive warfare has ended. Modern conflicts occur within populations rather than between armies, with objectives focused on behavior modification rather than territorial conquest or enemy destruction.Kaldor’s “New Wars”

Mary Kaldor highlighted the fragmentation of conflict actors beyond state militaries to include:

These actors operate within civilian populations, making traditional battlefield distinctions impossible.Sun Tzu in the Digital Age

Sun Tzu’s principle of winning without fighting finds modern expression through:

1.2 Seven Principles of Contemporary Conflict

Integrating these frameworks yields seven governing principles:

Principle 1: Continuity

Conflict operates continuously at varying intensities. There is no distinct “peacetime”—only phases of strategic competition.

Principle 2: Societal Battlefield

The primary battlespace is not military formations but civilian populations, infrastructure, perceptions, and governance systems.

Principle 3: Information Primacy

Narrative construction, perception management, and information control often outweigh kinetic effects in achieving strategic objectives.

Principle 4: Political Essence

All military, economic, and informational actions serve political objectives. Tactical success without political gain is strategic failure.

Principle 5: Cultural Dimension

Identity, civilizational worldviews, and cultural narratives shape both strategy formulation and conflict perception.

Principle 6: Multi-Domain Integration

Land, maritime, air, space, cyber, and cognitive domains function as a single integrated battlespace requiring synchronized action.

Principle 7: Indecisiveness

Contemporary conflicts rarely conclude with decisive victory. They terminate through exhaustion, negotiation, or systemic collapse.II. CHINESE GREY-ZONE METHODOLOGY2.1 Strategic Objectives

China’s South China Sea strategy pursues three interlocking objectives:

2.2 Salami-Slicing Tactics

Salami-slicing achieves strategic objectives through incremental actions, each below the threshold justifying military response:

Characteristic Actions:

Strategic Logic:

Each action appears insufficient to justify escalation. Cumulatively, they achieve irreversible facts on the ground (or water). The defender faces a dilemma: accept each small encroachment or risk disproportionate escalation.2.3 Cabbage Strategy

The cabbage strategy creates physical control through layered encirclement:

Layer 1 (Inner): Maritime Militia

Ostensibly civilian fishing vessels equipped with:

Layer 2 (Middle): China Coast Guard

Paramilitary vessels employing:

Layer 3 (Outer): People’s Liberation Army Navy

Military vessels providing:

Operational Effect:

The target feature becomes inaccessible without penetrating multiple layers, each requiring progressively higher levels of force. The encircled party faces isolation, resupply denial, and eventual surrender of the feature without shots fired.2.4 Exploitation of Asymmetries

Chinese grey-zone tactics exploit several asymmetries:

Legal Asymmetry:

International law constrains defenders more than aggressors. The Philippines cannot use military force against “civilian” militia vessels.

Bureaucratic Asymmetry:

China’s unified command structure enables rapid decisions and coordinated actions. Philippine interagency processes are slower and more fragmented.

Economic Asymmetry:

China can absorb economic costs of sustained operations and impose economic punishment on the Philippines through trade restrictions, tourism bans, and investment withdrawal.

Temporal Asymmetry:

China operates on strategic timelines measured in decades. Democratic governments face electoral cycles and public opinion pressures for immediate results.III. PHILIPPINE PORCUPINE DEFENSE: ASSESSMENT3.1 Strategic Concept

The Porcupine Defense employs Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) capabilities to make aggression prohibitively costly. Core elements include:

3.2 Effectiveness AnalysisHIGH EFFECTIVENESS: Major Aggression Deterrence

Scenario: Conventional Seizure of Pag-asa Island

The Porcupine Defense effectively deters this scenario through:

Assessment: China is unlikely to attempt overt military seizure of inhabited Philippine-controlled features while A2/AD systems remain credible.MODERATE EFFECTIVENESS: Grey-Zone Harassment

Scenario: Coast Guard Water Cannon Attacks on Resupply Missions

Limited effectiveness due to:

Assessment: Porcupine quills cannot deter actions below the lethal threshold.LOW EFFECTIVENESS: Incremental Encroachment

Scenario: Maritime Militia Swarming

Minimal effectiveness because:

Assessment: Military deterrence is irrelevant against “civilian” actors.CRITICAL VULNERABILITY: Cabbage Encirclement

Scenario: Three-Layer Encirclement of Ayungin Shoal (BRP Sierra Madre)

The Porcupine Defense cannot address this scenario because:

Assessment: Once encirclement is established, military options become catastrophically escalatory.3.3 Gap AnalysisRequirementCurrent CapabilityGap Persistent maritime presence Limited PCG/Navy patrols 24/7 coverage required Non-lethal response tools Water cannons (limited) LRADs, dazzlers, drone harassment Real-time maritime domain awareness Intermittent radar/satellite Continuous ISR coverage Unified command structure Fragmented agencies National Maritime Council Embedded allied presence Episodic exercises Persistent rotational deployment Civilian maritime capacity Unorganized fishermen Trained MDA network Rapid resupply capability Vulnerable large vessels Distributed small craft IV. RECOMMENDED FRAMEWORK: INTEGRATED GREY-ZONE DEFENSE SYSTEM

To defeat salami-slicing and cabbage tactics, the Philippines must supplement military deterrence with four additional capability layers:4.1 Layer 1: “Banana Peel” – Persistent Presence

Objective: Deny China the ability to establish facts on the water through continuous Filipino presence.

Components:

Philippine Coast Guard Expansion

Autonomous Systems

Maritime Domain Awareness

Effect: Chinese vessels cannot establish presence without immediate detection and Filipino counter-presence.4.2 Layer 2: “Coconut Shield” – Civilian Engagement

Objective: Create a civilian buffer and transparency mechanism that constrains Chinese freedom of action.

Components:

Fisherfolk MDA Network

Transparency Infrastructure

Community Alert Systems

Effect: Chinese grey-zone operations face immediate international exposure and Filipino civilian witnesses, raising diplomatic costs.4.3 Layer 3: “Bamboo Spear” – Non-Lethal Response

Objective: Provide sub-threshold response options that match Chinese grey-zone tactics without triggering escalation.

Components:

Acoustic Systems

Optical Systems

Physical Systems

Electronic Systems

Effect: Philippines can match Chinese grey-zone intensity without escalating to lethal force, restoring tactical symmetry.4.4 Layer 4: “Rattan Weave” – Institutional Integration

Objective: Unify fragmented Philippine government agencies into a coherent grey-zone response system.

Components:

National Maritime Council

Proposed membership:

Functions:

Standard Operating Procedures

Develop graduated response matrices:

Unified Training

Effect: Philippines responds to Chinese actions in hours rather than days or weeks, closing the decision-cycle gap.4.5 Layer 5: “Allied Bamboo Grove” – Persistent International Presence

Objective: Embed allied maritime forces to neutralize Chinese ambiguity and raise intervention thresholds.

Components:

U.S. Coast Guard Embedding

Rotating Allied Presence

Multilateral Mechanisms

Legal Framework

Effect: Chinese grey-zone operations risk confrontation with multiple nations, dramatically increasing political and military costs.V. IMPLEMENTATION ROADMAPPhase 1: Immediate Actions (0-6 months)

Priority 1: Establish National Maritime Council

Priority 2: Expand Persistent Presence

Priority 3: Enhance Allied Coordination

Phase 2: Capability Development (6-24 months)

Procurement

Infrastructure

Training

Phase 3: Full Operational Capability (24-48 months)

Integration

Phase 4: Sustainment (48+ months)

Maintenance

VI. RISK ASSESSMENT6.1 Implementation Risks

Bureaucratic Resistance

Risk: Agencies resist integration into unified command structureMitigation: Presidential directive with clear authorities, maintain agency operational independence while coordinating at strategic level

Resource Constraints

Risk: Insufficient funding for capability acquisitionMitigation: Phased implementation prioritizing low-cost/high-impact measures, leverage allied security assistance, seek multilateral development funding

Chinese Escalation

Risk: China responds to enhanced Philippine posture with increased pressureMitigation: Emphasize defensive and transparent nature, coordinate messaging with allies, maintain escalation control protocols

Allied Hesitation

Risk: Partners reluctant to establish persistent presenceMitigation: Frame as routine cooperation rather than confrontation, start with lower-profile technical partnerships, demonstrate Philippine capability improvements6.2 Strategic Risks of Inaction

Salami-Slicing Success

Without enhanced posture, China will continue incremental encroachment until:

Fait Accompli

China may complete major projects (e.g., Sabina Shoal installation) before Philippines can respond, presenting:

Alliance Credibility

Philippine inability to defend its claims may lead allies to:

VII. CONCLUSION

The age of decisive military conflict has yielded to an era of continuous competition waged primarily through non-military means. China’s systematic employment of grey-zone tactics in the South China Sea represents the paradigmatic challenge of this new strategic environment.

The Philippine Porcupine Defense, while effective at deterring conventional military aggression, cannot alone defeat salami-slicing and cabbage encirclement tactics. These approaches exploit the gap between military deterrence and political acquiescence.

Closing this gap requires transforming Philippine maritime security posture from a purely military deterrent into an integrated Grey-Zone Defense System combining five mutually reinforcing layers:

This framework respects three critical realities:

The strategic question is not whether the Philippines can militarily defeat China—it cannot. The question is whether the Philippines can make incremental Chinese expansion sufficiently costly, diplomatically complicated, and operationally difficult that Beijing concludes the West Philippine Sea is not worth the comprehensive national effort required.

In an age of infinite conflict, security belongs not to nations with the largest militaries but to those that adapt most effectively across all domains of competition. The Philippines must evolve accordingly.ANNEXESAnnex A: Critical Feature Risk Matrix Feature Strategic Value Encirclement Risk Current Posture Recommended Action Ayungin (BRP Sierra Madre) Critical High Vulnerable garrison Persistent PCG presence, rapid resupply capability, allied observation Sabina Shoal High Critical No permanent presence Immediate civilian presence, buoy deployment, continuous patrol Pag-asa Island Critical Moderate Civilian population, small garrison Infrastructure hardening, A2/AD emplacement, expanded facilities Escoda Shoal High High No permanent presence Automated monitoring systems, periodic patrols Panganiban Reef Moderate Low Minimal presence Maintain current posture, monitor Annex B: Comparative Grey-Zone Capabilities Capability China Philippines (Current) Philippines (Recommended) Maritime Militia 200+ vessels 0 Organized fisherfolk network Coast Guard Vessels 150+ 80+ 120+ with enhanced endurance Persistent ISR Continuous Intermittent Continuous (autonomous systems) Non-lethal Response Extensive Limited Comprehensive suite Command Integration Unified Fragmented National Maritime Council Allied Presence None Episodic Persistent rotational Annex C: Budget Estimates Program Element Years 1-2 (USD Million) Years 3-5 (USD Million) Annual Sustainment Patrol Vessels 200 300 50 Non-lethal Systems 50 30

Much too long for me to digest right now. It is a proposed operations plan for gray zone tactics that is probably a little too much for what the Philippines can do right now (using fishing vessels for tracking, blocking). Someone in Defense should translate this into “doable now”, “doable within 5 years”, and “rejected”.

Hope this is short enough

Japan and the Philippines have significantly strengthened their strategic partnership across military, economic, and other fields, driven by shared democratic values and mutual concerns over regional security. Key developments include a landmark defense pact, robust economic ties through trade and aid, and extensive people-to-people exchanges.

Military and Defense Cooperation

Military cooperation has deepened rapidly, particularly with the signing and entry into force of several key agreements aimed at enhancing interoperability and deterrence capabilities amid regional tensions in the South China Sea.

Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA): This landmark pact, in force since September 11, 2025, provides the legal and administrative framework for the two nations to deploy their forces to each other’s territory for joint training, exercises, and disaster relief operations.

Defense Equipment and Technology Transfer: The Philippines was the first ASEAN country to establish this cooperation with Japan in 2016. Japan is transferring defense equipment, including coastal surveillance radars and six Abukuma-class destroyer escorts, to bolster the Philippine Navy’s maritime domain awareness and capabilities.

Official Security Assistance (OSA): The Philippines was one of the first recipients of Japan’s OSA grant-aid framework, which provides military equipment and infrastructure support to like-minded countries.

Trilateral Cooperation: Both countries are actively strengthening trilateral cooperation with the United States, including joint military drills and strategic dialogues.

Economic Cooperation

Economic ties form a cornerstone of the relationship, with Japan being a vital trading partner and major source of development assistance for the Philippines.

Japan-Philippines Economic Partnership Agreement (JPEPA): This comprehensive agreement, signed in 2006, aims to increase trade and investment opportunities and facilitate the flow of goods, services, and capital.

Official Development Assistance (ODA): Japan has been the Philippines’ largest source of bilateral ODA for decades, providing significant funding for major infrastructure projects such as the Metro Manila Subway, the Davao City Bypass, and the North-South Commuter Railway.

Trade and Investment: Japan is a top trading partner, exporting high-tech goods, steel, and cars, while importing electronics, machinery, and agricultural products from the Philippines.

Other Areas of Partnership

Beyond security and economy, the partnership extends to various other sectors.

Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Response (HADR): A significant area of cooperation, with frameworks in place to enhance joint responses to natural disasters, which are frequent in the region.

People-to-People and Cultural Exchange: The nations promote mutual understanding through youth exchange programs like JENESYS and the JET Program, and aim to boost tourism.

Shared Values: The relationship is underpinned by shared fundamental values of freedom, democracy, and the rule of law, contributing to a shared purpose of preserving regional stability.

The Philippine Blue Revolution Framework:

A National Strategy for Ocean Innovation and Climate Resilience**

Date: 2025For: Office of the President, NEDA, DOE, DENR, DOST, DFA, PCG, Congress of the Philippines

Executive Summary

The Philippines’ 36 million hectares of maritime space represent a transformative opportunity to achieve energy security, climate resilience, and sustainable economic growth. Positioned within the Coral Triangle and over deep ocean trenches, the country is uniquely suited to develop ocean-based renewable energy, marine restoration, and blue economy innovation.

This policy brief outlines the Philippine Blue Revolution Framework—a 10-year national strategy that integrates ocean energy, conservation, community development, and technological leadership.

The framework recommends establishing a coherent legislative, financial, and institutional architecture to position the Philippines as ASEAN’s hub for ocean innovation.

The Problem

Despite vast marine resources, the Philippines remains highly vulnerable to:

Extreme dependence on imported fossil fuels (over 50% of energy supply)

Accelerating climate impacts (sea-level rise, stronger typhoons)

Declining fisheries and coastal livelihoods

Geopolitical pressure in the South China Sea

Current policies remain fragmented and heavily land-centric, leaving the maritime domain underutilized and underprotected.

Opportunity for National Transformation

The Philippines’ maritime geography offers:

OTEC potential using deep cold-water reservoirs (Philippine Trench)

Consistent wind, wave, and tidal energy corridors

Biodiversity-rich ecosystems ideal for restoration-linked financing

Strategic position for regional blue economy leadership

Large, youthful workforce suitable for new maritime industries

Harnessing these assets aligns with national goals under PDP 2023–2028, NDC commitments, and the Blue Economy Roadmap.

Core Policy Recommendations

A unifying law that:

Creates clear permitting and environmental standards

Establishes local community benefit-sharing

Mandates technology transfer for foreign investors

Defines decommissioning and marine habitat restoration obligations

Legally grounds the National Ocean Data Platform and Blue Energy Single Window

A centralized interagency process integrating DOE, DENR, BFAR, PCG, NAMRIA, and DOST to:

Streamline approvals

Prevent overlapping jurisdiction

Require real-time environmental compliance

Reduce transaction time and investor uncertainty

Prioritize 2–3 strategic locations for:

OTEC + offshore wind + wave energy hybrid platforms

Typhoon-resilient engineering trials

Co-located marine restoration (artificial reefs, coral propagation)

Aquaculture, desalination, and hydrogen demonstration projects

These pilots will form the foundation for commercial-scale deployment.

Use blue bonds to finance:

Ocean energy infrastructure

Large-scale coral and fisheries restoration

National ocean monitoring and digital twin platforms

Community co-ownership of ocean energy projects

Design returns around measurable ecological and climate outcomes.

A blended financing facility supporting:

Filipino ocean technology startups

Local supply chain development

Community-led enterprises (e.g., seaweed, mariculture, eco-tourism)

University research and sensor network development

Ensure blue economy benefits reach coastal communities:

Mandate 5–10% community equity in ocean energy projects

TESDA maritime energy training tracks

Women-focused blue workforce programs

Social safeguards for displaced or affected stakeholders

A digital twin system integrating:

Satellite mapping

IoT marine sensors

Real-time ecological monitoring

Extreme weather prediction and risk assessment

Maritime domain awareness (civilian + PCG/Navy)

Supports both development and national security.

Through:

Regional standards for tropical ocean technologies

Joint ASEAN ocean science initiatives

Shared best practices on marine spatial planning

Blue carbon and OTEC cooperation with Indonesia, Palau, Vietnam, Japan

Expected Outcomes (10-Year Horizon)

Environmental

Net positive biodiversity in project sites

Recovered reef systems

Measurable carbon sequestration and emissions reduction

Economic

3–5 GW new renewable capacity from ocean sources

Emergence of new blue economy industries

Exportable Filipino-designed ocean engineering

Increased FDI and climate finance

Social

200,000–300,000 new blue economy jobs

Improved livelihoods of coastal and indigenous communities

Major workforce upskilling in marine technology

Security

Enhanced maritime domain awareness

Increased civilian-military cooperation

Resilient energy supply insulated from regional shocks

Risks and Mitigation

Risk Mitigation Measure

Typhoon damage to platforms Cyclone Resilience Fund; structurally over-engineered designs

Ecological disruption Real-time monitoring; adaptive management; mandatory impact thresholds

Social displacement Equity-sharing, consultation, compensation mechanisms

Investor uncertainty Clear legislation; single-window approval; stable tariffs; blue bond guarantees

Geopolitical interference PCG-Navy support; secure science zones; diplomatic deterrence

Recommended Immediate Actions (Next 12 Months)

Philippine Rise

Mindoro Strait

Surigao Trench corridor

Conclusion

The Blue Revolution Framework provides a realistic, forward-looking path to secure energy, restore ecosystems, expand livelihoods, and strengthen national resilience. With coordinated legislation, financing, science, and community empowerment, the Philippines can transform its maritime domain into a strategic engine of prosperity and climate leadership.

The moment to act is now—before climate impacts intensify and before other nations define the regional blue economy agenda.

I hope this becomes an operating framework with implementation laws and follow through.

I hope so too.

Leasing Ports for a Modern Philippine Navy: A Strategic Imperative

The Philippine Navy (PN) is undergoing a significant modernization, highlighted by the acquisition of advanced guided-missile frigates and offshore patrol vessels from South Korea’s HD Hyundai Heavy Industries. These vessels, equipped with vertical launch systems, surface-to-air missiles, and anti-ship missiles, represent a major leap in combat capability for a fleet historically limited by outdated platforms. This modernization aligns with the Philippines’ strategic imperative to strengthen its deterrence amid rising tensions in the South China Sea.

However, enhancing naval capability requires more than ships; it necessitates a supporting network of ports and naval facilities. The archipelagic nature of the Philippines provides ample port locations, including over 120 commercial ports, numerous fishing ports, industrial jetties, and natural anchorages. Yet, most are not militarily ready—they lack hardened fuel storage, secure communications, repair facilities, and air defense.

Building permanent naval bases across the archipelago would be costly, slow, and strategically inflexible. In contrast, leasing ports from the Philippine Ports Authority (PPA) or private owners offers a faster, more cost-effective alternative. Long-term leases or standby activation agreements allow the PN to maintain peacetime commercial operations while retaining rapid wartime access, enabling a dispersed, survivable fleet posture. Security concerns can be managed through zoning, AFP detachments, and contractual clauses ensuring cooperation during crises. Strategic hubs like Subic Bay and Puerto Princesa can be permanently hardened, while leased ports support distributed operations for frigates, offshore patrol vessels, and smaller combatants.

This approach allows the PN to implement an archipelagic, forward-and-seaward defense doctrine, emphasizing fleet dispersal, operational flexibility, and survivability over centralized, vulnerable bases. By combining a few permanent strategic bases with a network of leased ports equipped with modular logistics and maintenance capabilities, the Philippines can maximize the effectiveness of its modernized fleet while minimizing costs and bureaucratic hurdles.

In conclusion, leasing ports rather than building new bases represents a pragmatic, strategic solution for the Philippine Navy. It aligns with regional realities, supports rapid modernization, and ensures that the nation’s enhanced naval capabilities—including South Korean-built frigates—can be fully operationalized to defend maritime sovereignty efficiently and sustainably.

A more pragmatic approach for countries like the Philippines could focus on prioritized, phased capability development rather than attempting full-spectrum modernization all at once: