Mining Our Past, Saving Our Future: Why the Philippines Needs Landfill Mining and Smart WtE

Posted by Karl Garcia on December 13, 2025 · 27 Comments

By Karl Garcia

Beyond slogans, beyond moral fights, toward industrial-scale environmental solutions

For decades, environmental debates in the Philippines have revolved around a single, tired binary: Zero Waste vs. Incineration. NGOs condemn burning. LGUs defend Waste-to-Energy (WtE). Corporations stay silent. And while the debate rages, rivers clog, mountains are mined, landfills overflow, and cities sprawl over unmanaged waste.

Amid all this, one transformative strategy has been largely ignored: Landfill Mining.

I. Landfill Mining: The Hidden Revolution

Landfills are not just piles of trash—they are urban ore bodies containing:

Construction and demolition debris

Soil-like materials

Metals, plastics, asphalt, and glass

Through Enhanced Landfill Mining (ELFM), these materials can be recovered and reprocessed into:

Aggregates for roads, buildings, and disaster reconstruction

Stabilized soil for urban development

Methane capture systems reducing greenhouse gas emissions

Globally, cities in Europe and Japan already treat old dumpsites as urban quarries, closing material loops while reclaiming land. The Philippines, with scarce land, destructive quarrying, and decades of buried waste, could gain enormous ecological, economic, and social benefits.

II. Why the Idea Remains Invisible

- Activism is stuck in the 1990s: Most NGOs focus only on waste reduction, segregation, and anti-incineration campaigns, leaving no room for industrial solutions.

- No clear villain exists: Landfill mining is systemic, technical, and lacks emotional imagery—hard to mobilize a protest around.

- Distrust of industrial solutions: Machines, plants, and heavy equipment trigger reflexive opposition.

- Misunderstanding of benefits: LFM restores land, reduces methane, and recovers materials—but is often dismissed as “just moving trash.”

- Government silence: Agencies like DENR, NEDA, and DPWH have not mainstreamed landfill mining. No policy signal = no advocacy traction.

III. Landfill Mining as a National Development Strategy

Landfill mining is more than waste management—it addresses multiple national priorities:

Legacy waste: Remediates decades of buried garbage.

Quarrying substitution: Reduces sand, gravel, and limestone extraction from rivers and mountains.

Urban land reclamation: Converts old dumpsites into industrial zones, solar farms, parks, or housing.

Methane reduction: Eliminates major short-term greenhouse gas sources.

Circular economy alignment: Supplies recycled materials, supports ESG goals, and fosters sustainable construction.

Green jobs: Transitions informal waste pickers into formal, safer, and better-paid roles.

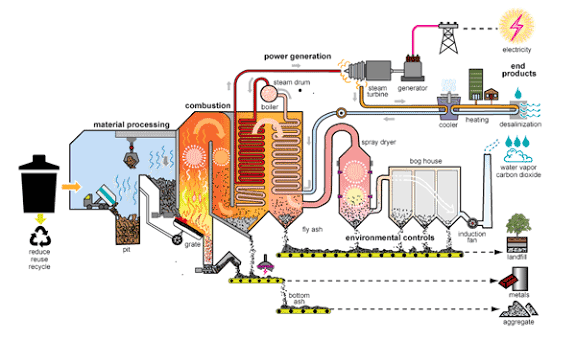

IV. Waste-to-Energy: A Complement, Not a Competitor

Looking ahead, the Philippines may see 10–15 large-scale WtE plants and several dozen modular systems in the next decade. Adoption will vary, with cities like Quezon City, Manila, Cebu, Davao, Baguio, and Dumaguete serving as key battlegrounds.

WtE success depends on:

- Operational reliability of flagship plants like New Clark City.

- Transparent, real-time emissions data for public accountability.

- Strengthened recycling and segregation systems so WtE complements, rather than competes with, circular economy goals.

WtE does not require activist approval—it must win community trust, LGU cooperation, and public confidence. It is not a silver bullet and should never replace recycling or composting, but it can play a practical role in a balanced, transparent, accountable waste ecosystem.

V. Reframing the Debate

The old frame:

“Should we burn or bury waste?”

The new frame:

“Should we keep mining mountains—or mine the resources buried in our own landfills?”

This shifts environmentalism from moralistic protest to industrial circularity and resource management, making advocacy about solutions rather than slogans.

VI. What a 21st-Century Philippine Environmental Movement Should Fight For

- Nationwide Enhanced Landfill Mining (ELFM): Integrated with C&D recycling, soil remediation, methane capture, and urban redevelopment.

- National standards for recycled aggregates: Certifying use in roads, concrete, slope protection, and infrastructure.

- Phase-out of destructive quarrying: Replaced with recovered aggregates, industrial by-products, and low-carbon construction materials.

- Circular procurement policies: Government favors recycled and low-carbon materials.

- Green job pathways: Transition informal waste workers to skilled, formal employment.

- Industrial circularity, not just behavioral change: Focus on material recovery and systems-level solutions rather than lifestyle moralism.

VII. Conclusion

The Philippines cannot keep fighting yesterday’s environmental battles. Landfill mining and responsible WtE together offer a practical, circular, climate-conscious, and industrially scalable solution.

The real question is not:

“Where do we put our trash?”

It is:

“Why are we still destroying mountains when mountains of resources lie buried in our landfills?”

The opportunity is clear: do less harm, create more value, and reclaim the future.

All that’s missing is political imagination and public courage to demand it.

______________________________________

Cover photo from PCIJ 2023 article “Has the Philippines created a garbage problem too big to dig its way out of?“.

The Philippines is a prodigious producer of trash, a consuming nation of 110 million people tossing it everywhere. The solution seems to me to be one part conscience and one part money. Conscience would cause us to lead ourselves to use more discipline in how we dispose of trash and to encourage government to fund solutions if they are not privately profitable. The money question is, is it privately profitable with existing technology? If it is, start mining. If not, visit conscience.

They say that if you have a conscience you don’t have to think twice.

Sadly the same can be said if you do not have a conscience.

Waste colonialism. First world chides castigates reprimand the third world snd yet they export their garbage.

https://earth.org/waste-colonialism-a-brief-history-of-dumping-rich-countries-trash-in-the-global-south/

Having conscience or bereft or lack of it

More on waste colonialism

https://www.crikey.com.au/2025/12/12/waste-colonialism-australian-clothes-recycled-in-the-pacific/

Discipline and Conscience: Beating Waste Colonialism through Landfill Mining

Landfill mining offers a practical path to addressing the global waste crisis, but technology and policy alone will not defeat waste colonialism. The deeper problem lies in the lack of discipline in how societies produce and consume, and the absence of conscience in how waste is governed. Without these human factors, landfill mining risks becoming another extractive activity that cleans up yesterday’s mess while enabling tomorrow’s neglect.

Discipline means designing systems that do not tolerate waste as a normal outcome of economic activity. Supportive government policies, financial incentives, and streamlined permitting must be paired with firm accountability—making recovery, reuse, and recycling cheaper than dumping. Investments in advanced technologies such as AI-driven sorting and robotics should be standard practice, not optional enhancements, ensuring maximum material and energy recovery from existing landfills.

Conscience, meanwhile, reframes waste as a moral and environmental debt. Landfill mining should prioritize the recovery of valuable materials and renewable energy while protecting workers, communities, and ecosystems. Beyond extraction, rehabilitating mined landfill sites into safe and productive land uses—parks, renewable energy sites, or community infrastructure—signals responsibility to future generations.

Together, discipline and conscience transform landfill mining from a technical solution into an ethical one. By embedding these values into public-private partnerships and circular economy strategies, societies can confront their own waste instead of exporting it elsewhere. In doing so, landfill mining becomes not just a tool for cleaning up the past, but a commitment to a more responsible and sustainable future.

Ah, ethical solution it is!

Cleaning the Seas That Define Us

The Philippines is a nation shaped by water. With more than 7,600 islands, our oceans are highways, pantries, storm buffers, and sources of identity. Yet every year, thousands of tons of plastic waste flow from our rivers into the sea, quietly undermining fisheries, tourism, and coastal livelihoods. Marine pollution is not an abstract environmental issue—it is an economic and social threat hiding in plain sight.

For years, the country has relied on piecemeal solutions. Cleanup drives remove trash after it washes ashore. River-mouth nets installed by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) intercept waste before it reaches the ocean. These efforts matter, but they are not enough. Plastic pollution is dynamic, driven by monsoons, floods, and typhoons. What we face is a systems problem—and it demands a systems solution.

This is where Ocean Savior PH comes in.

Ocean Savior PH is a concept that combines solar-powered, AI-guided cleanup vessels, modular debris collection systems, and community-based river interception to stop waste from river to reef. It borrows lessons from Boyan Slat’s Ocean Cleanup—particularly the use of data and modular design—but adapts them to Philippine realities. Our seas are not stable gyres. They are narrow straits, shifting currents, and storm-prone waters. Passive barriers alone will not work here.

Active, AI-guided vessels can. By tracking debris movement in real time, these vessels can reposition themselves as currents change, intercept trash during storm surges, and operate in coastal hotspots where most pollution originates. When paired with river-mouth nets managed by local communities, they create a continuous cleanup chain—from inland rivers to open sea.

The value of this approach goes beyond cleaner coastlines. Protecting marine ecosystems means protecting food security for millions of Filipinos. It means safeguarding tourism revenues for island provinces. It means reducing long-term cleanup costs that local governments can ill afford. Just as important, it creates opportunities for green jobs, local innovation, and environmental data collection that can guide smarter policy.

Critics may say this sounds ambitious or expensive. But the real cost is in doing nothing. Plastic pollution degrades fisheries, damages coral reefs, and weakens coastal resilience to storms—costs that far exceed the investment required for prevention and interception. Technology, when properly adapted and locally grounded, is not a luxury. It is a tool for survival.

The Philippines cannot clean its seas with isolated projects and good intentions alone. We need integrated, forward-looking solutions that recognize our geography, our climate risks, and our dependence on healthy oceans. Ocean Savior PH is not a silver bullet—but it is a credible step toward a future where technology, communities, and nature work together to protect the waters that define us.

Yes — there are real, existing AI‑assisted and tech‑driven initiatives currently being used (or piloted) for the Pasig River cleanup. Here are the key examples:

🛥️ 1. ClearBot — Solar‑Powered, AI‑Enabled Cleanup Vessel

One of the most prominent AI‑assisted cleanup technologies now active in the Pasig River is ClearBot:

What it is: A solar‑powered, electric vessel equipped with AI and cameras that can autonomously collect floating waste and thick vegetation like water hyacinths. It’s designed to operate for long hours and navigate shallow waters.

How AI helps:

Detects and identifies floating debris and distinguishes types of waste.

Avoids obstacles like other boats and even animals using AI vision systems.

Collects GPS‑tagged data and imagery on waste distribution to build digital maps / digital twins of pollution hotspots.

Deployment:

Two ClearBot vessels are deployed in a pilot project coordinated by the MMDA, Asian Development Bank (ADB), and local cities (Pasig, Makati, San Juan).

The pilot runs through January 2026 to assess effectiveness in local river conditions.

This is a real, operational example of AI being woven into river cleanup logistics rather than just a theoretical proposal.

📊 2. AI‑Powered Litter Detection Tools (e.g., LitterLens)

There are AI systems focused on monitoring and quantifying visible litter:

Tools like LitterLens use computer vision to detect, classify, and count litter in images taken from waterways (including portions of the Pasig River), producing real‑time data that can support smarter cleanup planning.

While not a mechanical cleanup robot like ClearBot, systems like this provide data intelligence that can guide where and how cleanup resources are deployed.

🤝 3. Broader Technology & Digital Planning Integration

Planners working on the Pasig River rehabilitation are increasingly incorporating AI & digital mapping into strategic cleanup frameworks, including:

Digital twin and predictive planning frameworks (e.g., maps of waste and hydrology) connected to cleanup tech.

These aren’t single products but represent the system‑level integration of AI/tech into policy and operational planning.

🧠 How These Fit into the Larger Pasig River Cleanup Effort

These AI‑enabled tools are part of a broader suite of cleanup initiatives, which also include:

Regular manual cleanups by agencies like the DENR‑Pasig River Coordinating & Management Office (PRCMO) and its River Warriors.

Motorized trash skimmer boats and heavy equipment used for removing hyacinths and debris.

Sustainable community and industrial waste management projects (e.g., RiverRecycle systems converting collected plastic into reusable products).

📌 In Summary

Existing AI‑assisted Pasig River cleanup technologies include:

✅ ClearBot autonomous cleanup vessels — AI + solar‑electric boats collecting waste and generating data.✅ AI‑driven litter detection systems (like LitterLens) — real‑time monitoring and classification.✅ AI/data integration into planning frameworks for targeting cleanup and monitoring effectiveness.

These technologies are currently being piloted or used alongside traditional cleanup operations — marking a practical step toward smart, tech‑enhanced environmental management for the Pasig River.

Terrific. I think the Philippines is starting to come out of the backward age.

Interesting to use applied AI here.

Post-landfill mining, or Enhanced Landfill Mining (ELFM), reframes legacy dumpsites not as environmental liabilities but as deferred resource deposits. Decades of municipal and industrial waste now contain recoverable aluminum, copper, steel, precious metals from early e-waste, and even rare earth elements embedded in discarded electronics. Through modern mechanical separation and modular refining—favoring lower-energy hydrometallurgy where feasible—ELFM converts buried waste into domestic material streams, reducing import dependence while anchoring circular manufacturing ecosystems.

Beyond metals, ELFM delivers measurable carbon and waste optimization gains. Excavation and sorting eliminate long-term methane generation, while biogenic waste can be converted into refuse-derived fuel for cement kilns and plastics into pyrolysis oil or syngas. These pathways reduce emissions, generate verifiable carbon credits, and lower future remediation costs. Inert fractions—glass, ash, and soil-like materials—can be stabilized and certified as secondary construction inputs, closing the loop between waste recovery and infrastructure delivery.

A critical but often overlooked benefit is land reclamation and risk reduction. Removing unstable waste masses allows controlled regrading, improved slope stability, and the elimination of leachate threats. Former dumps can be repurposed for flood buffers, renewable energy siting, or eco-industrial parks—transforming stranded land into productive public assets while shrinking long-term government liabilities.

ELFM also directly supports road building and construction. Recovered aggregates are suitable for road base, embankments, and flood-control levees, reducing quarry extraction, transport emissions, and project costs for local governments. Processed materials can be used in non-structural concrete, bricks, and geopolymer cements, linking waste recovery to affordable, low-carbon construction.

Taken together, ELFM is not merely waste management; it is resource extraction, climate mitigation, and land regeneration integrated into one system. For countries facing urban land scarcity, infrastructure backlogs, metal import dependence, and rising climate adaptation costs, post-landfill mining emerges as a pragmatic national resilience tool—turning yesterday’s waste into tomorrow’s materials, land, and climate dividends.

Below is a focused exploration of successful landfill mining (Enhanced Landfill Mining / ELFM) with Japan as the anchor case, followed by Europe and other proven regions—highlighting why they worked, what was recovered, and what lessons apply to the Philippines and other archipelagic states. 🇯🇵 Japan: Landfill Mining as Industrial Resource Recovery Why Japan Succeeds

Japan’s landfill mining success is tightly linked to:

Key Practices

1. Incineration Ash Mining

Recovered Materials

2. Slag & Construction Material Reuse

3. Closed-loop Urban Mining

Outcomes

Key Insight:

🇧🇪 Belgium (EU Flagship): Enhanced Landfill Mining (ELFM) The REMO Project (Limburg)

Recovered

Innovations

Outcome

🇳🇱 Netherlands: Landfill Mining + Circular Economy Dutch Model

Key Advantage

🇸🇪 Sweden: Energy-Centric Landfill Mining Approach

Result

🇨🇭 Switzerland: Precision & Environmental Safety Focus

What Makes These Projects Successful (Common Factors) Factor Why It Matters Strong regulation Prevents environmental backlash Advanced sorting tech Makes low-grade materials viable Metal price sensitivity Projects scale when prices rise Land scarcity Forces recovery over expansion Public–private partnerships Shares risk and capital Long-term planning ELFM works over decades, not years Strategic Lessons for the Philippines & Similar States

Given your ongoing work on post-landfill mining, road building, land reclamation, and rare earth recovery, these lessons are highly transferable: 1. Start with Ash & Coastal Landfills

2. Target High-Value Outputs

3. Integrate with National Goals

4. Use ELFM as Climate Adaptation

Bottom Line

Japan and Europe prove that landfill mining works when it is:

Urban mining—recovering strategic materials from discarded electronics, vehicles, batteries, buildings, and other “above-ground stocks”—has become an explicit priority of the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) because of supply-chain risk for critical minerals (rare earths, lithium, cobalt, nickel, antimony, tungsten, etc.).

Below is a clear, defense-policy–oriented snapshot of how the DoD approaches urban mining, who’s involved, and why it matters. 1. Why Urban Mining Matters to the DoD

The DoD is concerned with supply security, not just sustainability.

Key drivers

Urban mining advantages

2. DoD Agencies Involved A. Office of Industrial Base Policy (IBP)

The lead DoD office for critical minerals security.

Focus areas

IBP funds pilot plants and first-of-kind facilities that commercial markets won’t initially support. B. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA)

DARPA treats urban mining as a technology problem.

Relevant programs

DARPA’s angle: “How do we recover mission-critical materials faster, cleaner, and at scale?” C. Strategic Materials Programs (Title III – Defense Production Act)

Under DPA Title III, DoD directly invests in:

These programs often include offtake guarantees, de-risking private investment. 3. What Materials the DoD Targets via Urban Mining High-priority materials

Urban mining sources include:

4. Examples of DoD-Backed Urban Mining Efforts Rare Earth Recycling

Battery Recycling

Defense Asset Demilitarization

5. Strategic Doctrine: “Above-Ground Reserves”

The DoD increasingly treats waste streams as:

This aligns with:

Urban mining is not a substitute for traditional mining—but a force multiplier. 6. Relevance to the Philippines (Policy Insight)

For an archipelagic, import-dependent country like the Philippines, the DoD model suggests:

This dovetails strongly with ELFM (Enhanced Landfill Mining), port electrification, and maritime-industrial strategy. Bottom Line

The U.S. DoD views urban mining as a national security capability, not just environmental policy.

It is:

Below is a systems-level concept for an ideal co-located compound facility that integrates landfill recovery, WtE, MRF, REE recovery, power generation, and materials remanufacturing—framed around Philippine realities and opportunities. The Ideal Co-Locating Compound Facility

“Waste → Resources → Energy → Industry” Core Principle

Treat waste as a strategic domestic resource, not a disposal problem.

The compound functions as a circular industrial ecosystem, where outputs of one process become inputs of another. 1. Landfill Mining + Residual Waste Intake (ELFM)

Function

Philippine Promise

Outputs

2. Advanced Materials Recovery Facility (MRF 2.0)

Function

Upgrade from Traditional MRFs

Outputs

3. Rare Earth & Critical Minerals Recovery (REE Hub)

Function

Strategic Value

Outputs

4. Waste-to-Energy (WtE) Power Plant

Function

Energy Uses

Philippine Context

5. Remanufacturing & Materials Reprocessing Zone

Function Turn recovered materials into higher-value products, not just raw recyclables.

Examples

Economic Impact

6. Environmental & Land Restoration Integration

Function

Climate Benefits

7. Governance & Financing Architecture (Philippine Fit)

Best Structure

Revenue Stack

Why This Is a Philippine Promise

One-Line Vision

Landfills, Rainfall, and the Limits of Zero Waste

Even in a society where no one litters or dumps illegally, heavy rainfall can turn landfills into sources of environmental pollution. When rainwater percolates through waste, it creates leachate—a toxic liquid containing organic matter, heavy metals, ammonia, and pathogens. During intense downpours, leachate volumes often exceed the landfill’s containment and treatment capacity. Flooding can overwhelm collection systems, erode slopes, and wash exposed waste into rivers and coastal waters. Legacy landfills, particularly those built before modern engineering standards, are especially vulnerable to leakage during extreme weather events—a situation exacerbated by climate change, which increases rainfall intensity and flood frequency.

This reality underscores a critical distinction: “zero waste” does not equal “zero pollution.” Zero waste policies aim to reduce, reuse, and recycle materials, but even a small fraction of residual waste can end up in landfills. In tropical, flood-prone countries like the Philippines, these landfills inherently pose environmental risk, independent of human behavior.

Consequently, eliminating landfills altogether—rather than simply reducing waste—is a stronger safeguard for ecosystems and public health. Zero landfills remove the structural risk of leachate and flood-driven garbage release. In practice, this requires aggressive material reduction, circular recovery systems, composting, anaerobic digestion, and safe handling of residual materials. Legacy landfill sites can be addressed through enhanced landfill mining, recovering resources while restoring land.

In sum, the hierarchy of sustainable waste management for climate-vulnerable regions should prioritize zero landfills first, followed by circular systems and near-zero waste generation. While zero waste reduces volumes, zero landfills eliminate the structural environmental threat, providing a more resilient and climate-proof approach to urban and coastal sustainability.

Mining Waste as a Resource: Precious and Strategic Metals in the Philippines

The Philippines, located on the Pacific Ring of Fire, is rich in mineral resources. Historically, mining practices prioritized a single metal, leaving large volumes of tailings, slag, and waste rock that still contain valuable metals. Modern recovery technologies now make it possible to extract these overlooked resources, turning former waste into economic and strategic assets.

Gold and silver remain the most immediately recoverable precious metals. Old gold tailings from areas like Benguet, Masbate, and Paracale still contain measurable gold concentrations, often alongside silver, which were not fully extracted in previous operations. Similarly, copper tailings from porphyry mines, as well as nickel and cobalt in laterite deposits, offer significant reprocessing opportunities. Chromium, iron, and even trace platinum group metals further expand the potential value of mining waste.

Beyond traditional mining sites, urban landfills contain ferrous and non-ferrous metals from construction, appliances, and scrap materials, representing another layer of recoverable resources. Recovering metals from these sites not only generates revenue but also mitigates environmental risks, such as tailings dam failures and heavy metal pollution.

Reprocessing mining waste aligns with both economic and strategic objectives. It provides a source of metals critical for clean energy, batteries, and defense, while reducing the environmental footprint of past mining. By treating waste as a resource, the Philippines can transform legacy liabilities into sustainable opportunities, supporting economic growth, environmental protection, and national security.

Not a priority I think. Priority is responsible primary mining.

Sovereignty and the Reality of Military Bases

Concerns about national sovereignty often arise when foreign militaries operate within a country. In the Philippine context, some fear that agreements like EDCA (Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement) or foreign presence in ports and facilities could undermine sovereignty. However, such fears are largely overstated.

Building permanent military bases is a lengthy and complex process, even for advanced militaries like that of the United States. Full-scale construction, logistics, and operational setup can take years, meaning that immediate threats to territorial control are minimal. EDCA already provides a framework for temporary deployments, joint exercises, and rotational presence, ensuring that the Philippines retains full authority over its facilities.

Temporary use of ports or facilities allows for rapid operational flexibility without permanently ceding control. Compared to rushing to build new bases, this approach is more practical, cost-effective, and respectful of sovereignty. In an archipelagic nation with multiple strategic points, rotational presence and shared facilities offer both security and operational readiness while maintaining national control.

Ultimately, the combination of long timelines for permanent bases and legal agreements like EDCA ensures that sovereignty is preserved, even as the country strengthens its defense partnerships.

Not an issue I think. The Philippines is on top of this.

Thanks to Teodoro.

Perfect. Here’s a feasible roadmap for recovering metals and materials from old mines and garbage dumps in the Philippines, broken down step by step:

1. Assessment & Mapping

Old Mines:

Landfills/Dumps:

Outcome: A “resource map” showing potential extraction hotspots.2. Technology Selection

Old Mines:

Landfills/Dumps:

3. Pilot Projects

Goal: Prove feasibility and attract private investment.4. Regulation & Incentives

5. Scaling Up

6. Circular Economy Integration

7. Cost-Benefit & Strategic Advantages

It should be a private initiative. Government has more important things to invest in.

But DOST has to seek partners like what they are doing with other projects.

Desalination plants are primarily designed to produce fresh water from seawater, but their operation also generates by-products and concentrated brine, which can contain recoverable minerals. The potential precious and industrial minerals include:

These are the main salts and minerals present at higher concentrations in brine:

Sodium chloride (NaCl) – main component, industrial salt.

Magnesium (Mg) – can be recovered as magnesium hydroxide or magnesium metal.

Calcium (Ca) – calcium carbonate or calcium oxide for industrial uses.

Potassium (K) – potassium salts for fertilizers.

Sulfates (SO₄²⁻) – e.g., magnesium sulfate (Epsom salt).

While in smaller concentrations than in natural ores, desalination brine may contain trace amounts of:

Lithium (Li) – in seawater at ~0.17 ppm; increasingly valuable for batteries.

Bromine (Br) – in seawater at ~65 ppm; used in flame retardants, electronics, pharmaceuticals.

Strontium (Sr) – ~8 ppm in seawater; used in electronics, ceramics, and medical applications.

Uranium (U) – ~3 ppb; potentially recoverable with specialized extraction methods.

Rare Earth Elements (REEs) – e.g., yttrium, neodymium, and lanthanides in trace amounts; valuable for electronics and magnets.

Some innovative research focuses on “brine mining” from desalination plants:

Lithium recovery using selective ion-exchange membranes or adsorption.

Magnesium extraction for lightweight alloys or chemical industries.

Bromine recovery via chemical precipitation.

Calcium and carbonate minerals for cement or CO₂ sequestration applications.

Challenges

Concentrations of precious metals are low, so extraction is often costly and energy-intensive.

Environmental concerns with additional chemical processing.

Economically viable mostly when combined with large-scale desalination operations or integrated with industrial mineral recovery.

Desalinization is becoming a big deal in Cebu which has a fresh water shortage. I have no idea how they handle waste products. Again, the waste treatment is a secondary priority and should be a part of any major laws mandating or regulating waste.

Yes Joe thanks.