Half a Millenium after Magellan

Analysis and Opinion

By Irineo B. R. Salazar

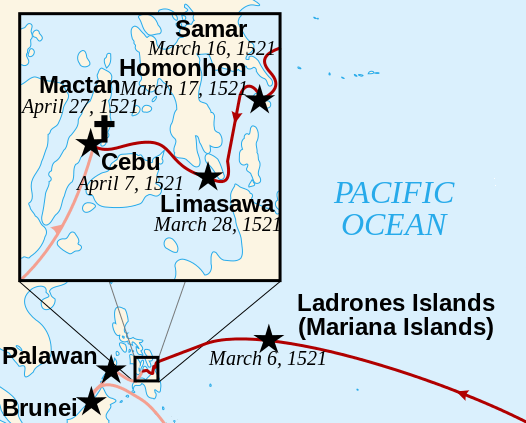

The late Yoyoy Villame sang “on March 16, 1521, the Philippines was discovered by Magellan” and the late Edgar Lores can be seen practically singing along in an old comment. That a wise man like Edgar likes a comedian’s song is not surprising to me, as Filipino humor is often a form of wisdom. Villame captures what the “discovery” means to Filipinos by praising the coming of Catholicism but also making fun of Magellan getting killed: “Mama, Mama, I am sick, call the doctor very quick!” Events of half a millennium have made the Philippines what it is now, and it somehow started then.

Magellan in the Philippines (source: Pinterest)

Some comments after Karl says: “were they looking for the spice girls. carlos de cinco must have wanted a carlos de sais. Instead he had felipe and Felipe is so makulit he kept on saying Felipe no, thus we are called Filipinos.” Well, indeed they were after spices, as Magellan had been part of the conquest of Malacca in 1511. His friend Serrão made his way to Ternate in the Moluccas, the Spice Islands, and was a sort of adviser to the Sultan there, getting killed the same year as Magellan.

This article is about what happened back then and the ensuing trajectory to today’s Philippines.

WHAT REALLY HAPPENED?

Accounts that Serrão was stranded in Mindanao on his way are unlikely, as the Moluccas to Mindanao is more than a thousand kilometers; maybe it was Manado in Sulawesi. By the same principle, I doubt that the the first mass was in Mazaua, Butuan and not in Limasawa. The sources say Kolambu, the first Filipino (Waray) chief they encountered, had volunteered to guide them to Cebu, and it simply doesn’t make sense to go the long way to Cebu, especially if a local is on board helping.

The master’s thesis „THE SPANISH PACIFICATION OF THE PHILIPPINES – 1565 – 1600“ is thorough with sourcesand easily readable. This disclaimer is obligatory though as it is a US Navy officer’s thesis: “The opinions and views expressed therein are those of the student author and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College or any other governmental agency”. The account of how rude Magellan actually was to Humabon, how the attack at Mactan took place at low tide (the chronicler Pigafetta writes that their cannons were out of range) and of course Humabon inviting Magellan’s men to a banquet after their defeat – to slaughter them – make me wonder if Lapu-Lapu and Humabon were just pretending to be enemies (moro-moro). Even as rivals over sea tolls, they may have engaged in a temporary alliance (pintakasi).

Written accounts are only the testimonial evidence of history, and the forensic evidence of history like archaeology and genetics can tell us about trade and living conditions or about migrations, but little about actual persons and events. In any case, Warays were documented as friendly to Magellan in March 16, 1521, but not as friendly to Villalobos (the one to call the archipelago Felipinas) over twenty years later. It is possible that they may have heard of what happened – and remembered.

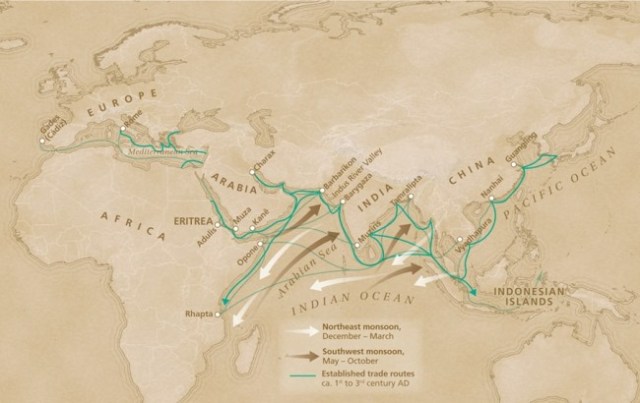

Indian Ocean Trading Network of two millennia ago (Source: Discover Magazine)

Recent research has revealed fascinating things about the bigger picture too, such as an Indian Ocean trading network which joined all three continents of Asia, Europe and Africa that already existed two millennia ago, nearly forgotten by history. Recent publications mention an earlier maritime trading network in the Indian Ocean by Austronesians, the first humans to venture oceanic voyages, with monsoon winds helping them get all the way to Madagascar. Filipinos are Austronesians, related not only Indonesians and Malaysians but also to the peoples of the Pacific. And they were not touched by foreign influence the first time in 1521. An article of mine here has described how Indian and Islamic influences reached maritime Southeast Asia way before Magellan. And Arab maps may well have helped the Portuguese find their way in the Indian Ocean. This does put Magellan into context.

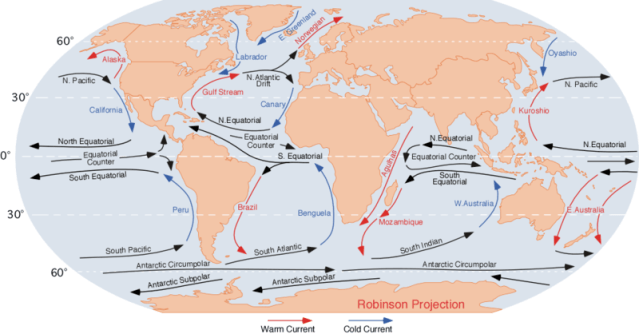

Commenter sonny asks in the comment thread where his fellow Ilocano Edgar sings: “Magellan stumbled upon our part of the Malay archipelago because of what? The standard answer is to seek the best route to the islands of Ternate & Tidore. The known route then was to hug the African coastline by going as far south as one can and then hang a left at the Straits of Malacca and go eastwards to the two islands”. The Treaty of Tordesillas of 1494 is part of the answer. A non-dashed straight line through the Atlantic split up the world between Spain and Portugal, very presumptuous, but it basically gave most of the Americas to Spain (Brazil just barely juts out of that line) and the Asian areas to Portugal. So Magellan decided to sail around the globe to get to the Moluccas, and possibly the sea currents that also pass through Guam where he was as well account for the drift. In any case, the expedition still even made a profit with spices Elcano brought back from Tidore, the rival of Ternate in the Moluccas. Two expeditions – Loaisa in 1526 and Saavedra(from Mexico) in 1528 – went straight for the Moluccas, but just managed to end up captured by the Portuguese.

So the Treaty of Zaragoza in 1529 put the Philippines to the West of a Pacific Ocean demarcation line, on the Portuguese “side” of the world. Villalobos nonetheless went for and named the Philippines in 1544. He ended up dying in Portuguese captivity. A mountain of silver discovered in Potosí, Bolivia in 1545 as the resource that was to fuel the galleon trade changed the business equation. Still the next expedition to sail to the Philippines started only in 1564 from Mexico – by order of Philipp II himself.

Legazpi was back in Cebu in 1565, including an episode described in the military master’s thesis with tuba (Cebuano liquor), young women and temptations which might amuse our commenter LCPL_X. Raja Tupas of Cebu was wary of the Spaniards who had this time come from Mexico in huge force. Urdaneta found the northward Pacific current and the tornaviaje, the way back to Mexico from there via the California coast, and soon reinforcements came. Finally Visayans from Panay and Cebu joined Legazpi in 1571 when he ventured towards Manila, then a Muslim ally of Brunei,and conquered it.

Through several challenges – Limahong in 1574, the attemptto attack Brunei in 1578 and the Tondo conspiracy of 1587-88(which had rebelling Manila nobles asking for help from Brunei and Palawan), Spanish Manila soon consolidated itself as hub of the galleon trade, mainly Chinese wares for silverfrom the Andes. Ming dynasty loyalist Koxinga in 1620 (who finally occupied Taiwan) was a further challenge that caused Spain to pull its troops out of most of Mindanao and the Moluccas. Finally, we have Sultan Kudarat saying this to Maranao datus in 1639: “Do you realize what subjection would reduce you to? A toilsome slavery under the Spaniards! Turn your eyes to the subject nations and look at the misery to which such glorious nations [Tagalogs & Visayans] have been reduced to.”

THE NATIONAL TRAJECTORY

Commenter sonny also asked this question: “How do we draw the historical trajectories we would like to be enlightened by? what national pathology would we like to trace and understand? our economics? our politics? our“damaged culture”? our “pathetic” religiosity? our colonial mentality? Questions, questions and more questions.Journalism 101 suggests we find the answers as to the Who, where, what, when, why, how of things. Our textbooks through the decades have fed us partial answers to these questions. Or is it just me who wonder about these things in this manner?” I attempt to find answers to that question using history, looking at trade, industry, land, power and freedom.

TRADE. The Suma Oriental of Tome Pires who had stayed in Malacca fascinatingly tells of Luçoes, most probably Luzonians, having three ships there, trading in gold, honey and beeswax and also trading with Borneo, that most were “heathens”, have “no kings, just elders” and are described as hardworking. Raiding, Trading and Feasting by Laura Lee Junker says the Philippines (Manila, Mindoro, Pangasinan, Cebu, Jolo and Cotabato) had trade with Thailand, Borneo, China and Japan (the latter mostly with Mindoro and Manila) at that time while the Sultanates of Maguindanao, Sulu and Brunei are mentioned as having been intermediaries in the China-Moluccas trade. After the Galleons by Benito Legarda furthermentions Filipino trade with Canton and the future“Indochina”.

The growing East Asian trade the Philippines was becoming part of died down in favor of the galleon trade. Native elites were shut out of it. Spaniards in the Philippines held precious cargo space on galleons based on their rank. The enterprising nature of Filipinos still came through with Filipinos jumping ship in Acapulco, where “tuba fresca” is sold to this day, Mexicans with Malay features in the state of Guerrero, and even Filipino religious groups in Mexico City that existed in early years.

Cash crop planting, mainly sugar, tobacco and abaca from the late 18th century onwards did revive foreign trade, with parts of the native elites (by then assimilated into the system as principalia), Chinese and Spanish mestizos rising up as a new elite, with a few foreigners and Spanish in the mix.

INDUSTRY. Junker mentions that craftsmen enjoyed a special status in the early Philippines and were protected by chiefs as the goods they produced were important for foreign trade. Blacksmiths that produced weapons (including Malay cannons called lantakas which defended the old wooden fortress of Manila), wood carvers, carpenters who built houses and boats, weavers of high quality. The Filipino carpenter my father usually hired produced furniture similar to the Balinese furniture sold for a high price in the West. Filipino weavers especially among the indigenous still produce magnificent cloth. One could think of craftsmen as the growing middle class of the old Philippines.

The galleon trade had use for hardworking Filipinos to build galleons and to man them – but not for the products they could create. Shipbuilding and weapon making of course regressed;I guess the Spaniards had no interest in technologies that could be used to attack them. The plantation economy that got started in the late 18th century did bring wealth and some technology that was used to process crops – sugarcane to sugar, making abaca shippable, tobacco into cigars etc. – but mostly stopped there as processing into finished products (for example shipping rope) was done abroad.

Low literacy will also have impeded industrialization – the Philippines only had 20% literacy pre-WW1, with rapid school expansion in the 1930s bringing it to middle range (30-75%) by the 1950s. But some say the US$-PHP fixed exchange rate of 1:2 after Independence in 1946 was a disadvantage as imported US goods were cheap and local goods uncompetitive internationally, the opposite of the situation in some other Asian countries. And reactive as sovery often, all the Philippines did when the exchange rate was lowered in 1962 and 1970 was to increase coconut land. The Bretton Woods era of fixed exchange rates only lasted until 1973, when the floating exchange rates of today started.

Marcos did try to attract foreign manufacturing via EPZA (export processing zones), a mechanism known as PEZA today, with heavy tax breaks. Even the later BPO boom heavily relied on PEZA. Walden Bello says that going all-in for neoliberalism from 1995 onwards damaged local industries such as shoes as they were exposed unprepared to foreign competition.

Real industrialization and innovation means investment. Seems it was always easier to make money with crops and with Filipino labor – indirectly as well via monopolistic utilities, malls and subdivisions.

LAND. William Henry Scott in Prehispanic Filipino Concepts of Land Rights mentions that land was not bought or sold in the Philippines before Spanish times. Junker says Spanish 16thand 17th century sources say the datu owned the lands and distributed them to his people – though those people were nebulously defined by the chief’s alliance network that expanded or contracted over time. Cordilleran leader Macli-ing Dulag famously said during the Marcos era that “Only the race owns the land as the the race lives forever”. Farmers were free in any case, not sharecroppers in those days.

Early Spanish conquest in the Philippines gave encomiendasto Spanish officers, exploitative land grants. The burden on the local economy including abandoned fields and formerly free peasants turned into debt slaves due to over taxation is known, causing private encomiendas to be abandoned unlike in Latin America. Public encomiendas, especially those run by monastic orders continued. Inquilinos, often native elites, leased land from the Church and had sharecroppers till the soil in exchange for a part of the harvest. Scott mentions how some native elites bought and sold land.

The reduccíon put Filipinos “under the bells”, though forced labor and taxation made some become remontados, while of course many in isolated areas were only gradually touched by colonial rule. Coconut planting started in 1642 as it supplied material for the galleons. Cash crop planting, mainly sugar, tobacco and abaca from the late 18th century onwards as well as population increasing from one to eight million in the 19thcentury decreased subsistence land, making banditry rampant.By contrast, Legarda says that the Philippines exported a lot of rice to China in the 1820s-1850s.

A Spanish initiative to legalize land titles in the late 19thcentury as well as the Torrens titling during the US period further concentrated property among those with awareness of the law. A Harvard Business School paper notes that many people were not able to title their land in the early American period as they lacked the money for the necessary legal fees. The sale of friar lands by the United States mostly benefitted those who already had money/power. The Colorum and Sakdal revolts of the 1920s and 1930s were due to yet more landless peasants. Land reform attempts all have failed.

Around 1600 there were around 800 thousand people in Luzon and the Visayas – a population density of five people per square kilometer, and around 250 thousand people in Mindanao – just 2.5 people per square kilometer. Metro Manila has 500 thousand people per square kilometer today, with no space left for pigs, chickens or goats some urban poor once kept. In rural areas mining and subdivisions have further reduced total arable land. Forest cover has declinedsignificantly (70% of the Philippines covered in 1900, 40% in the 1960s and only 23.7% by 1987), endangering watersheds.

POWER. Mayor Duterte infamously taunted Mar Roxas in a Presidential debate that one who is afraid of killing or being killed cannot be President. Bagobo tribal leaders in Mindanao also had tattoos as a mark of how many they had killed like the Visayans (called Pintados by the Spaniards due to their tattoos) and others did, but their leadership also arose from recognized maturity: “Followers can withdraw allegiance when the figure is no longer regarded as having preserved that admirable or compelling core energy.” What led to the present distortion of ancient tribal warrior values?

A paper with an objectionable name has revealing contents, mentioning how often Spain relied on native soldiers to suppress uprisings, and that often the native:Spanish ratio was 5:1. Some native soldiers joined due to debt, some for glory and ambition. Being soldiers against one’s own people, often with forced conscripts or even criminals as colleagues on the Spanish side, must have been one root of todays often mentioned culture of impunity. Spanish introducing the Guardia Civil in the 19th century (with Filipinos serving in it too), American introduction of the Constabulary in the 20thcentury (mainly Filipinos) and Marcos’ national consolidation of police forces just continued things.

Bagobo shield from Davao, pre-1910, from the University of Pennsylvania Museum

Though King Philipp II in 1594 recognized the rights of native elites, the principalia, they only had positions like cabeza de barangay (basically barangay captain) and gobernadorcillo (mayor) open to them. Province governors and above were Spaniards. Nobody in Aguinaldo’s Republic had experience running anything above municipal level. That gradually changed during American rule (Philippine Assembly in 1908, Senate from 1916, Insular Government) until the Commonwealth in 1935.

Even then after the war until 1991 the Philippines did not have to defend itself from outside threats, and only seriously embarked on what should have been the consequence of throwing out US bases – Armed Forces Modernization – in the time of President Benigno Aquino III. Filipino armed forces only fought against foreign troops in 1646 (against the Dutch with Spain), from 1896-1902 (against Spain and the USA) and 1942-44 (against Japan with the USA), otherwise mostly against Filipinos. General Tadiar NOT firing on fellow Filipinos on EDSA in 1986 strongly stands out in this context.

Local political families were already violent during Commonwealth times and often became warlords after World War 2. Some of them are vividly described in Alfred McCoy’s An Anarchy of Families. Martial law had centralization of armed power, ostensibly to deal with warlords and rebels, including a Communist rebellion that had reignited barely a decade after Magsaysay, and the Muslim rebellion partly rooted in land conflicts due to postwar migration to Mindanao. Gloria Arroyo restoked internal conflicts and it seems boughtmilitary leaders. The old issues in the countryside and the newer issues with urban poor remain unresolved, brutality still the main answer and worst today. This is all intertwined with issues of land in rural areas and not enough industry in urban areas.

FREEDOM. For centuries, uprisings were local in character, often due to over taxation, though some had an idea of freedom: Dagohoy for instance, a Visayan local leader who went up the mountains with his followers, who held out until after his death. Diego Silang allied with the British in trying to establish an independent Ilocano state, with his wife Gabriela continuing his fight after his death. Sometimes it was religious freedom: Tamblot was a very early rebel, a native priest who led a group of apostates in Bohol from 1621-22. HermanoPule was a leader of a native Christian group with 4000 followers in the 19th century. Filipino priests fought for equal status as well. Jesuits were initially expelled from the colony as they were considered too radical by some, and later allowed to return.

The 19th century also had the Bayot brothers in 1822 and Andreas Novales in 1823, all Philippine-born Spanish officers, shortly trying to go the same way as the creole Spaniards in Latin America. The children of the new commercial elites of the Philippines were able to attend college, and noticed the struggle between liberalizing and reactionary forces in Spain. Governor Carlos Maria dela Torre ruled from 1868-1871 and entertained the non-Castilian elites of the country in his palace. His successor Rafael Izquierdo was the opposite. A mutiny of soldiers in Cavite in 1872 was blamed on Gomburza(the reformist Filipino priests Gomez, Burgos and Zamora) who were garroted. Their execution politicized an entire generation, even some who went to Europe to study, much easier by then as the Suez Canal had opened in 1868. Rizal was of course among these ilustrados (enlightened ones).

Rizal portrayed in his novels how those with independent ideas were called filibusteros (subversives) by priests and authorities, the 19th-century equivalent of red tagging, with very similar dangers.

Jim Richardson’s “The Light of Liberty: Documents and Studies on the Katipunan, 1892-1897” and the page http://www.kasaysayan-kkk.info/ with original source material show that Bonifacio’s Katipunan had “membership.. from all classes” and “saw themselves as continuing the work of Rizal, Marcelo del Pilar and other propagandists” i.e. the ilustrados in Europe and “was at its core a modern, forward-looking organization, rationalist and secular.” Certainly it had members who used cult-like symbols, and bandit-like characters. Bonifacio mentioned that without well-being (kaginhawaan) and decency (kabutihang-loob) there was no use for freedom. The former I think recognized the enormous gap in wealth and the latter echoed Rizal’s “what if the slaves of today become the tyrants of tomorrow”. Both Rizal and Bonifacio I think recognized the potential of Filipinos to be nasty to one another.

Manolo Quezon describes the Philippine revolution, the Japanese occupation, the late Marcos era and the present pandemic as major economic catastrophes with grandparents as witnesses to the previous one. Economic precariousness can often breed a mentality of every group for itself.

Add to that a middle class not mainly built upon own industrialization or a stable agricultural base. Bonifaciobelonged to a new middle class employed in foreign trade houses, just like today’s new middle class was partly due to BPO money. Though the old middle class was instrumental to EDSA, a lot of them had already left from 1965-1985 and even more left afterwards. A stable middle class is essential to a real democracy, but the new middle class from OFW and BPO money voted Duterte. Does that come from the same insecurity that attracted the old middle class to Marcos before 1972?

Also interesting is that the first Philippine election law in 1907 required one to have been a local official in the Spanish Philippines, have a certain minimum wealth or be literate. Literacy was retained as a requirement in the 1935 Constitution but dropped by the 1973 Constitution. Previously I mentioned that broad literacy only existed starting with the 1950s. Let us also consider what world many Filipino’s grandparents or parents grew up in. Manila did have first electricity in the 1890s, but by 1969 only 5.8% of homes in rural areas were electrified. In addition the public education system was already messed up in the 1970s; I recall that children from Balara dropped out because of a no-fail policy because of which some no longer managed to catch up with subjects. I know of a former teacher in Cagayan who in the 1970s went uphill to teach kids who did not even speak Ilocano, much less Filipino or English. I guess many like her left the country due to those conditions and low salary.Creating the broad general education needed for democracy seems to have failed, looking at this.

By EDSA Dos/Tres society had become highly fragmented.The 2016 election, the political ignorance of many who got Facebook via free data and later high poll ratings for Duterteshocked many people.

THE PHILIPPINES TODAY

Of course I am not an expert, just someone trying to put together a huge puzzle with missing pieces. But what I have been able to put together so far, also in the Going Home seriesof articles together with Karl, could explain a lot of the issues many have observed about the Philippines today:

- Weakness of civic society and democratic institutionscaused by lack of conviction/cohesion

- Social injustice caused by huge wealth gaps and lack of strong industry and agriculture

- Power that often rejects accountability and people who try not to offend the powerful

- A violent streak in society coming from both the powerful and the desperately powerless

- A unevenly educated, mostly unenlightened society thatoften demonizes thinkers/activists

Joe already has identified the messed-up situation when it comes to land and lack of opportunity as major factors that need to be addressed for the well-being of most Filipinos. Filipinos going abroad as OFWs since 1975 may actually have saved the country from major implosion or total civil war. Inspite of EPZA, later PEZA, foreign factories have come and gone, so a stable base of blue-collar jobs is still missing. BPO did help create the new middle class but that is transitory if not used to ramp up one’s own innovation. Just as an own stable industrial base and productive agriculture are important.

My essay The National Village was about the persistence of village-like attitudes even when it comes to the nation. Gideon Lasco also says in The Philippines Is Not A Small Countrythat the Philippines is bigger than Italy and significantly larger than Britain, and that Mindanao is larger than Ireland – and that thinking the Philippines is small is self-limiting. The classic “Heritage of Smallness” essay of Nick Joaquin already said: “Society for the Filipino is a small rowboat: the barangay. Geography for the Filipino is a small locality: the barrio.” Lots of Filipinos are only generations removed from there. The Netflix series Trese and the comic that preceded it indeed go by a very interesting premise: “When Filipinos moved out of the provinces to the city, did they bring their monsters and gods with them?”

The supernatural detective Alexandra Trese is also described as a babaylan, the term for the ancient priestesses of the Philippines, who were displaced by Spanish friars in the villages of old. The friars employed clever strategies in the islands, such as teaching the children of the principalia first as well as using the fiesta, latching onto the power of chiefs and the old culture of feasting. A culture whose languages are all still basically gender-neutral imbibed a strong patriarchal influence in the process.

The unique mix of native and Christian elements, the role of cultic symbols even in the Katipunan which was at its core progressive, the mix of Christian symbolism and democratic ideals at EDSA, the contrasts between the fictional Padre Damaso and the meteorologist Padre Faura, the male Black Nazarene and the female Lady of Peñafrancia – all of this has very old roots, most certainly even the present clashesbetween President Duterte and those around him with a lot of strong women.

Possibly the difficulty some Filipinos have in understanding satire has to do with being taught to receive what is said by elders, the powerful and the knowledgeable as gospel truth. Recently, satire by Duterte Watchdog on Twitter was believed by many. He made Tito Sotto “say” that two doses of Sinovacvaccine have 100% efficacy because each has 50% efficacy. Interestingly, Jim Paredes, whose band Apo Hiking Society had heavily satirized Marcos in a live album back in 1985, was one of the first to ask whether it was satire. Filipino humor was often part of resistance, even in Rizal’s Noli.

My article about Widening Philippine Horizons was also about how the world of perceptions and the world of what is dictated as true by many figures of authority prevent a more enlightened attitude. Now we certainly learn from past generations and would be naked without them, but it is also important for new generations to add their lessons learned to the culture (the sum total of all a people has learned in millennia, in my personal definition) so that it can adapt to new challenges.

For instance in the old days, you were a follower of a chief,nowadays of a politician or an ideological grouping. National settings may need a concept of pluralism, which Karl interestingly defines like this in his EDSA article (excerpt): “In my opinion, there should be a balance among the isms from Socialism to Neoliberalism. After all, another ism, called the prism, has many colors. Democracy does not mean irresponsible freedom. ..With inspirational leadership, there would always be trust.”

Will Villanueva though reacted to Karl’s EDSA article as follows (excerpt): “..No. Nothing works in the Philippines, nothing changes mindset, nothing pulls warring political tribes from the brink but God Himself.. ..The country is impervious to any change, as a gabi leaf resists water. It’s no wonder that President (ugh!) Duterte’s first acts were to distance himself and the country from God our redeemer by calling Him stupid and cursing the Pope..” Major point, as it is always shared beliefs that keep pluralism from turning into chaos. Even a Constitution is a secular kind of Ten Commandments.

In a recent lecture, novelist Ninotchka Rosca said that Filipinos – unlike Japanese, Koreans and even Indonesians – lack introspection. Opinions like above exchanged due to Karl’s recent EDSA article, also on Twitter, show the mustard seed of introspection can grow. It may need to be watered more.

Half a Millenium After Magellan, how will Filipinos take charge of their future national trajectory? What path to the future and what kind of future will they decide on? Will it be for better or worse?

Irineo B. R. Salazar

München, 23 February 2021

Comments

276 Responses to “Half a Millenium after Magellan”Trackbacks

Check out what others are saying...-

[…] a major influx of settlers and soldiers, being just three weeks away. So as I already outlined in Half a Millenium After Magellan, colonization happened with the participation of local chiefs and warriors. I have read that in […]

-

[…] a what if scenario of Magellan being delayed, drowning in a typhoon in June 1521 instead of arriving on March 16, 1521, who knows? […]

“Today, we commemorate the landing of the Magellan-Elcano expedition 500 years ago in what would become #PH. Warays gave comfort & succor to the sick & starving crew of the expedition. The @nqcPhilippines leads the commemoration w/ a series of events beginning TODAY.”

https://www.quora.com/profile/Danny-Gerona – Bicolano Magellan expert

https://youtube.com/channel/UCiXITL7Be22cvTZMbKstdGg YouTube channel

https://philippinediaryproject.com/author/antonio-pigafetta/ the chronicler

https://philippinediaryproject.com/author/francisco-albo/ the navigator

Antonio Pigafetta, a Florentine navigator who went with Magellan on the first voyage around the world, wrote, upon his passage through our southern lands of America, a strictly accurate account that nonetheless resembles a venture into fantasy. In it he recorded that he had seen hogs with navels on their haunches, clawless birds whose hens laid eggs on the backs of their mates, and others still, resembling tongueless pelicans, with beaks like spoons. He wrote of having seen a misbegotten creature with the head and ears of a mule, a camel’s body, the legs of a deer and the whinny of a horse. He described how the first native encountered in Patagonia was confronted with a mirror, whereupon that impassioned giant lost his senses to the terror of his own image.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Nobel Laureate Lecture

Thus did Gabriel Garcia Marquez begin his 1982 Nobel Lecture. A Filipino looking at this lecture by the Father of Magical Realism might then turn to our very own Father of Tropical Baroque, Nick Joaquin, who, in a lecture of his own, delivered at the University of San Carlos in Cebu on April 21, 1979 put forward this argument:

I know that the current approved fashion is to assert that our 400 years as a Western colony was merely an irrelevant interlude: not our history but an interruption of it; and that our true history is our development into a free nation of Asian culture. In this view, Lapu-Lapu is important as the first in a long line of heroes to resist the culture of the West; and our colonial history must be read as one long resistance movement, a movement that continued Lapu-Lapu’s heroic refusal to submit to the invading culture.

That refusal was, of course, a definite reaction; but I think we tend to think that to react is always to go against: to resist or to reject. But to accept is also a reaction. To modify what is accepted is also a reaction. To change and be changed is also a reaction. Our folk Catholicism is as much a reaction to Christianity as, say, the novels of Rizal.

Our resistance to Western culture is part of our history, of course, but only one part. The other half is our acceptance of that culture, the way we adapted it to our own uses, the way we modified it and were modified by it.

When we say yes to something we are reacting as definitely to it as when we say no. In fact, when it comes to culture, reaction is often both a yes and a no at one and the same time. This is obvious in today’s Pinoy rock, which is our reaction to Western pop music. We say yes to that music by accepting its beat; but at the same time we say no to it by filipinizing that beat, by recreating rock into a “sariling atin.”

Who of us would say now that the carabao-with-plow is not Philippine? Yet that entity, the carabao-and-plow, was a colonial creation, being our version of Western agriculture as it was in the 16th century. When we accepted the plow and the idea of a draft animal, weren’t we making history? Or are we to say that this development in our agriculture is not part of our history because “true” Philippine history must always mean the rejection, not the acceptance, of the invading culture? Yet the Filipino, if he is anything at all, is the product of the plow, not to mention the wheel, the road and bridge, the Roman alphabet, the printing press, the guitar, and all the other tools that invaded us in the 16th and 17th centuries.

That is why I say that the Filipino is the result of a reaction to Western culture. And that is also why I can not say that the Filipino is the result of a reaction to Asian culture. And why not? Because there was little or no Asian culture for us to react to. Because, throughout our prehistory, Asia is conspicuous by its absence. In fact, all those centuries before 1521 should not have been a prehistory for us but a fully enlightened history, if Asia had been generous enough to make us a part of its history, of its culture, of itself. But, to repeat, Asia, before 1521, was conspicuous by its absence in Philippine culture.

Nick Joaquin, “Lapu-Lapu and Humabon: The Filipino As Twins.” Paper read at the Symposium on Lapulapu, held at the University of San Carlos on April 21, 1979, under the auspices of the Cebuano Studies Center, the History Department of USC and the Ministry of Youth and Sports Development (Region VII).

https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=2348350395298554&id=100003708496009 – Xiao Chua:

ON MARCH SIXTEEN FIFTEEN HUNDRED TWENTY ONE…

ARMADA DE MALUCO:

ANG EKSPEDISYON NI MAGELLAN AT ELCANO

BILANG TAGUMPAY NG AGHAM AT SANGKATAUHAN

AT ANG BAHAGI NG PILIPINAS PARA MAISAKATUPARAN ITO

Michael Charleston “Xiao” B. Chua

Pamantasang De La Salle Maynila

Noong 2019, ginunita ang ika-limandaang taon (Kwinsentenaryo) ng paglalayag ng ARMADA DE MALUCO (MAGELLAN-ELCANO EXPEDITION). Sa Martes gugunitain naman ang ika-limandaang taon ng pagkakapadpad nila dito.

Ngunit ano ba ang kahalagahan nito sa ating kasaysayan?

Noong pagsisimula ng ika-16 na siglo, nais ng kapwa Espanya at Portugal na mamayani sa paglalayag at pagdiskubre ng mga lupain dahil sa pangangailangan na makapangalakal ng kahit anong maitutumbas sa ginto. Ang tawag sa sistemang ito ay merkantilismo.

Gayundin, nagkaroon sila ng mga tratado sa Santo Papa na tinatawag na Patronato Real, upang ang mga kaharian na ito ay mapondohan ang mga misyunero na magpapakalat ng Katolisismo kapalit ng pagkilala sa awtoridad ng Espanya at Portugal sa kanilang mga sinakop na lupain.

Sa pamamagitan ng Kasunduan ng Tordesillas noong 1494, hinati ng Simbahan ang mundo. Lahat ng hindi pa nasasakop na lupain sa kaliwa ng 46°30′ kaliwa ng Greenwich ay sa Espanya habang ang sa kanan naman nito ay sa Portugal.

Isang lugar na nasakop ng mga Portuges sa Asya ay ang Malacca (nasa Malaysia ngayon), kung saan dinadala ang mga rekado na nagmumula sa mga isla ng Moluccas (nasa Indonesia ngayon), ang tinaguriang “Spice Islands” na hawak ng mga Muslim.

Isang kawal na Portuges, si Ferdinand Magellan, na nadestino na sa Malacca noon ay lumipat sa Espanya at nagpanukala sa hari nito na kaya niyang tumungo sa Moluccas nang hindi dumadaan sa Asya o sa mga Portuges dahil nga bilog ang mundo, at dahil dito may posibilidad pa na masakop ng Espanya ang Moluccas dahil wala na ito sa lugar na para sa mga Portuges.

Nagustuhan ng Hari ng Espanya, ang Santo Emperador Romano na si Carlos Quinto ang mungkahi ni Magellan. Nangutang ang hari sa mga bangkerong Aleman na Fugger upang tustusan ang grupo ng limang barkong tinatawag na “nao” at iba pang gastusin upang nakapaglayag ang ekspedisyon. Ang grupo ng barko, o Armada, ay binubuo ng limang nao: Ang Trinidad ang pangunahing barko kung saan si Magellan mismo ang kapitan, San Antonio, Concepcion, Victoria at Santiago.

Isinama ni Magellan sa paglalakbay si Antonio Pigafetta, isang maginoong taga-Venecia na ang papel sa ekspedisyon ay sumulat ng mga tala ng kasaysayan ng ekspedisyon; at ang kanyang alipin na si Enrique na nakuha niya mula sa Malacca na naging mahalagang bahagi ng paglalakbay pagdating sa kapuluang ito dahil maalam pala siya sa mga wika ng mga narito.

Maraming nagtaas ng kilay sa pagkakatalaga sa isang kaduda-dudang dayuhan tulad ni Magellan para sa misyon. Isa na dito ang makapangyarihang pinuno ng Casa de Contratacion ng Espanya na si Obispo Juan Rodriguez Cardinal Fonseca subalit nakakuha rin sa Magellan ng kasunduan sa hari at sa Casa de Contratacion na kung anuman ang kikitain sa mga nasakop na lupain para sa Espanya ay makikinabang at magkakaroon ng bahagi ang mga tagapagtuklas at ang kanilang mga susunod na salinlahi!

Ito ang diwa ng empresa at pakikipagsapalaran na nagdala kay Magellan, bagong kasal lamang sa isang dilag na taga-Sevilla na iwan ang kanyang aristokratang pamumuhay at pamunuan ang Armada de Maluco na umalis ng Espanya noong 20 Setyembre 1519.

Ang Armada de Maluco ang naging dahilan ng pagkakadiskubre ng ruta upang makalusot ang mga barko mula Atlantiko patungong Pasipiko. Ito ay naisakatuparan sa kabila nang bagyo, lamig, lungkot at napakahirap na kapaligran sa pinakadulong bahagi ng Timog Amerika. Dito napatunayan ang galing ni Magellan bilang manlalayag at sa kanyang tagumpay ipinangalan sa kanya ang lagusang ito—ang Straits of Magellan.

Ang paglalakbay ni Columbus patungo sa America ay tatlumpu’t limang araw lamang, ngunit inabot ng mahigit isang taon na ang paglalakabay ni Magellan. Hapong-hapo at gutom na gutom na sila sa dami ng buwan sa karagatan at iba’t ibang problema tulad nang pag-aalsa at pagtakas ng ibang kasamahan, nang matagpuan nila ang Guam at ang Pilipinas.

Akala natin na ang dumating ang mga Espanyol sa Pilipinas na malalakas na mga mananakop pero dumating talaga silang lupaypay at takot. Ngunit nilapitan sila ng ating mga ninuno mula sa Suluan (ngayo’y Guiuan, Eastern Samar) at kahit hindi nagkaintindihan, alam ng mga ninuno na nangangailangan ang mga ito. Sanay rin sila sa pakikipagkalakalan at walang kinikilalang kulay o lahi ang kanilang kabutihan. Bumalik sila nang may dalawang bangkang pagkain at kinalinga ang mga maysakit. Maaaring namatay na sa panghihina ang mga tao sa Armada sa puntong iyon at wala tayong pag-uusapan na unang pag-ikot ng mundo.

At bagama’t pinasisinungalingan ang sinasabing nadikubre ng mga Espanyol ang mga Pilipino ng mga historyador ngayon, mas maganda sigurong sabihin sa sa mga pangyayari noong 1521 ay mas nadiskubre o mas nakilala natin ang isa’t isa.

Ang pagkakapadpad nila sa Pilipinas ang muling nagbigay sigla sa paglalakbay dahil sa kasaganaan na kanilang nasumpungan sa mga islang ito. Ito ay sa kabila ng pagkamatay ni Magellan dito noong 27 Abril 1521 sa kamay ni Lapulapu at ng mga taga Mactan; at ng iba pang mga pinuno ng armada sa kamay ng mga taga Cebu. Ito ay matapos panghimasukan ang ating mga ugnayan. Kumbaga, pinapakita ng mga ninuno natin na mabuti kami sa lahat ngunit aalma kami sa panghihimasok ng dayuhan.

Ngunit sa kabila nito, ang pagkapadpad sa Pilipinas ang nagbigay daan para ang ang natitirang tatlong barko ay makatungo sa Moluccas at nakuha rin nila ang mga rekadong kanilang pinakaaasam-asam.

Sa 260 katao na lumayag kasama ng ekspedisyon noong 1519, 18 na nangangayayat at hapong-hapong mga tauhan na lamang ang nakabalik sa Espanya sakay ng iisang barko, Ang Victoria, noong 1522 ngunit dala-dala nila ang mga mahahalagang rekadong sibuyas at kanela. Ang kinilala ng hari na pinakaunang umikot sa mundo ay ang pinuno ng Armada na nakabalik, si Juan Sebastian Elcano, subalit alam natin na hindi niya ito matatamo kung wala si Magellan at ang kanyang diwang mapagsapalaran. Mas nakilala natin ang mundong ating ginagalawan nang dahil sa kanya.

Ang pagkilala na ito sa tagumpay na dulot ng Ekspedisyong Magellan-Elcano at ang palitan ng kultura na nangyari dahil sa enkuwentro na ito ng mga Espanyol at mga Pilipino ay hindi dapat na maging daan upang hindi naman kilalanin na ang mga paggalugad na ito ang nagbigay-daan sa magiging kolonisasyon ng Pilipinas at dapat matuto rin at pag-usapan ang mga hindi magandang naiduliot nito.

Dahil bahagi ang Pilipinas sa kuwento ng trahedya at punyagi ng Armada de Maluco, na isang tagumpay sa sandaigdigan, ay dapat lamang nating pag-alayan ng interes at pagpapahalaga ang kuwento nito lalo na ngayong kwinsentenaryo o limandaang taong anibersaryo ng Tagumpay at Pakikipagkapwa-tao sa Mactan sa 2021.

For further reading:

Bergreen, Laurence. 2004. Over the edge of the world: Magellan’s terrifying circumnavigation of the globe. New York: Perennial.

Gerona, Danilo Madrid. 2016. Ferdinand Magellan: The Armada de Maluco and the European discovery of the Philippines. Naga City: Spanish Galleon Publishing.

Guillemard, Francis, Antonio Pigafetta, Francisco Albo, and Gaspar Correa. 2008. Magellan. England: Viartis.

Pigafetta, Antonio. 1906. Magellan’s voyage around the world (3 volumes), James Alexander Robertson, trans. Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark.

Pigafetta, Antonio. 2017. Unang paglalayag paikot ng daigdig, Phillip Yerro Kimpo, trans. Metro Manila: Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino.

Zweig, Stefan. 2011. Magellan. London: Pushkin Press.

https://www.facebook.com/UnyonNgMgaManunulatSaPilipinas/videos/854571091780984/ – the lecture where Ninotchka mentions introspection

https://twitter.com/mlq3/status/1371672243797827587 – more details on population which slightly correct my figures above:

“From the 1500’s when we had 2.6 million people which in 300 years only tripled; from then, we now have over 100 million: a growth of about 14x in 200 years.”

“Interesting is pre-American censusus (under Spain) begins with quoted figure of 667,612 taxable souls: but reckoning for that was actually per 4 heads, so: 2,670,448 in 1591! 1st Spanish government census in 1878: 5.5M; 1887: 5.9M; 1898 census never completed (7.8M is quoted).”

Via MLQ3, Leon Ma. Guerrero on the Spanish imprint on the Philippines (aka “Spanish Asia” as Joe once described it) https://twitter.com/mlq3/status/818253459132583936

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trade_route#Austronesian_maritime_trade_network

The first true maritime trade network in the Indian Ocean was by the Austronesian peoples of Island Southeast Asia,[52] who built the first ocean-going ships.[13] They established trade routes with Southern India and Sri Lanka as early as 1500 BC, ushering an exchange of material culture (like catamarans, outrigger boats, sewn-plank boats, and paan) and cultigens (like coconuts, sandalwood, bananas, and sugarcane); as well as connecting the material cultures of India and China. They constituted the majority of the Indian Ocean component of the spice trade network. Indonesians, in particular were trading in spices (mainly cinnamon and cassia) with East Africa using catamaran and outrigger boats and sailing with the help of the Westerlies in the Indian Ocean. This trade network expanded to reach as far as Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, resulting in the Austronesian colonization of Madagascar by the first half of the first millennium AD. It continued up to historic times, later becoming the Maritime Silk Road.[52][14][15][53][54] This trade network also included smaller trade routes within Island Southeast Asia, including the lingling-o jade network, and the trepanging network.

In eastern Austronesia, various traditional maritime trade networks also existed. Among them was the ancient Lapita trade network of Island Melanesia;[55] the Hiri trade cycle, Sepik Coast exchange, and the Kula ring of Papua New Guinea;[55] the ancient trading voyages in Micronesia between the Mariana Islands and the Caroline Islands (and possibly also New Guinea and the Philippines);[56] and the vast inter-island trade networks of Polynesia.[57]

(most sources mentioned in the Wiki as footnotes are very recent, i.e. this century. Lots of new evidence has been found)

“… This trade network also included smaller trade routes within Island Southeast Asia, including the lingling-o jade network, and the trepanging network.”

The first time (centennial year, 1998) I heard of this network was in the book edited by former Sec of Education, Ding de Jesus. It was in relation to slave raids of Muslims from Mindanao which were run at different times of the year for the purpose of slave labor from the other parts of the Philippine islands to keep the commercial trade with the Chinese. Trepang (sea cucumber) seemed to be an important trade item for the Chinese market.

An exhaustive analysis of the slave trade by Moro raiders conducted around the Philippines can be found in the book Philippine Social History: Global Trade and Local Transformations

PHILIPPINE SOCIAL HISTORY: GLOBAL TRADE AND LOCAL TRANSFORMATIONS, edited by Alfred McCoy and Edilberto De Jesus.

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/magellan-s-expedition-and-elcano-s-first-circumnavigation-of-the-globe/egJCFYTKUG3YLg interactive map

https://en.rutaelcano.com/la-primera-vuelta-al-mundo day by day account in Spanish and English

https://multimedia.expresso.pt/magalhaes2020/index-en.html#inicio around the world in 200 messages, interactive for kids

“What struck e most was Ninotchka’s observation that Filipinos lack introspection.

Growing up (maturity), developing one’s character and learning from mistakes are products of introspection.

Is she saying that Filipinos have arrested development?”

“Thanks, Ireneo.

The context is: Most Filipinos seems to always rely on something outside themselves to give them power instead of looking inward and finding that power in themselves. The Darna touch is edifying.”

“Today, @Philippine_Navy’s BRP Apolinario Mabini will meet the approaching @Armada_esp’s Juan Sebastián Elcano at sea, as the Elcano ship lands at Suluan Island, Guiuan, Eastern Samar #PH, to symbolically reenact the historic event 500 years ago.”

https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=590471141847421 Yoyoy Villame

https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=277989960356210&substory_index=1&id=100044356242925

Note on the Balangiga bells – they were repatriated also thanks to US veteran groups that lobbied for it..

https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=277989960356210&substory_index=0&id=100044356242925

LOOK: PhilPost employees show off the 200mm by 220mm 1734 Murillo Velarde map – the first scientific map of the Philippine archipelago nearly 300 years ago. (MB Photos by Ali Vicoy)

“Commenter sonny also asked this question: “How do we draw the historical trajectories we would like to be enlightened by? what national pathology would we like to trace and understand? our economics? our politics? our“damaged culture”? our “pathetic” religiosity? our colonial mentality? …”

I formulated these questions way back during the Philippine Centennial year 1998. The VFA was then happening. For me, it was a welcome event to counteract the “mistake” of the pullout of Clark and Subic bases. I also recall American pubic opinion was for the cost reduction of foreign bases expenditures; the bad taste of James Fallows’ A DAMAGED CULTURE, I never recovered from; the “pathetic” religiosity of Filipinos is something the secular mind will never understand nor sympathize with.

pubic = public, 🙂 as Karl would say Freudian typing slip. LC made me do it.

LOL! but actually MRP was the master of sexual innuendos and hidden meanings, I tend to be less poetic about these things. More direct, and practical, ie. over-population & nutrition solution.

“Legazpi was back in Cebu in 1565, including an episode described in the military master’s thesis with tuba (Cebuano liquor), young women and temptations which might amuse our commenter LCPL_X. “

From the same book above, the description of Spanish sailors and Humabon’s female constituents was pretty direct. I’ve always wanted to read it in its original from Pigafetta’s. Essentially, the sailors presented the young Cebuanas with trinkets and it was off to the forest they went for some DNA mixing, back when Cebu still had forests.

Now most of that is done on Mango Street.

I’ve always wondered what happened to the progeny of that first mixing. Did they all end up in Showbiz back in the 1540s? Or in the Lifestyle section of the newspapers back in the 1500s? By 1560s , when Legazpi returned, all that European-ness would’ve dissipated, so as historians and anthropologist only that small window of 1530s to 1550s is of interest, so the 50/50 mestizos would be the first, no?

Probably the southern parts would already have Arab mestizos. But with Europeans that would be the first.

The most similar encounter I read of, was in the Lewis & Clark expedition when they camped for the winter in the Mandan village, where they had a celebration in which young braves “donated” their wives to old braves (retired and old) in hopes of receiving their “medicine”– or power/luck/conatus . York, who was Clark’s slave was the most popular in said celebration as documented by the expedition.

I’m thinking Humabon encouraged his dalagas or even maybe wives , to assert close encounters of the seventh kind , hoping to gain from the visit. What that power may have generated is of interest, not just for Showbiz and Lifestyle sections.

p.s. — Ireneo, I wanted to introduce Walter Bagehot’s “English Constitution” (available as pdf and in youtube) to the previous blog, but I think its relevant here too per sonny‘s “Philippine software” comment below. As we know, there’s no written Constitution for the Brits, so Bagehot’s compendium is it. In it, Bagehot differentiates between Dignified and Efficient, efficient being the day to day routine of governance, whereas Dignified is the role of the Sovereign , its been chipped away for sure, but still what remains is the myth that the Crown answers to God alone, not the people. Very much like the Pope myth, or Quiboloy.

There’s no portion allocated for Dignified in the US Constitution as well as the Philippine Constitution. So maybe more Filipinos should be reading Walter Bagehot (pronounced like gadget). Just a thought. I gotta feeling chemp would be the expert on him amongst all of us here. If you can get him to comment on Bagehot, karl, please do. Paging chempo!

Have not been in touch with chempo for a long time, the last time was him sending holiday greetings in messenger to me.

LCPL_X, the entire journal of Pigafetta is now on the Web, day by day, thanks to MLQ3:

https://philippinediaryproject.com/author/antonio-pigafetta/

As for the episode with Legazpi, here it is:

Page 276: “The resignation to Spanish rule by Tupas represents the beginning of the pacification of the islands. During this initial period four issues arose that tend to reveal the differences and conflicts among the two cultures. The first concerned the drinking of tuba. After friendly relations had been established the people of Cebu began bringing various goods to the Spanish encampment, among these the drink tuba. Legazpi at ostensibly banned the trade in tuba because he stated that it was slightly alcoholic and encouraged people to go around drunk. However, the tuba vendors tended to be young women of the dependent class who had different attitudes regarding sex, noted in chapter two, than the staid and moralistic Legazpi. He forbade the women to enter the Spanish camp or to stay overnight, and admonished Tupas and the other elders for the

practice bot they made light of the situation. As a result of the prohibition, a lively market in tuba bars sprung up in the village.”

Mango Street, 1565?

Ah, thanks, this is perfect!!! But now, having flipped and scrolled thru these pages, the link you’ve given and am cross checking it to the only digitized version (in French , and I don’t speak a lick of French) available online that i’ve found,

the date in question is MLQIII’s 15th-25th April 1521 log,

[92] Those people go naked, wearing but one piece of palm-tree cloth about their private parts. The males, both young and old, have their penis pierced from one side to the other near the head, with a gold or tin bolt as large as a goose quill, and in both ends of the same bolt, some have what resembles a spur, with points upon the ends, and others [have] what resembles the head of a cart nail. I very often asked many, both old and young, to see their penis, because I could not believe it. In the middle of the bolt is a hole, through which they urinate. The bolt and the spurs always hold firm. They say that their women wish it so, and that if they did other- wise they would not have intercourse with them. When the men wish to have intercourse with their women, the women themselves take the penis, not in the regular way, and commence very gently to introduce it [into their vagina], with the spur on top first, and then the other part. When it is inside it takes its regular position; and thus the penis always stays inside until it gets soft, for otherwise they could not pull it out. Those people make use of that device because they are of a weak nature. They have as many wives as they wish, but one of them is the principal wife.

[93] Whenever any of our men went ashore, both by day and by night, they invited him to eat and to drink. Their viands are half cooked and very salty; they drink frequently and copiously from the jars through those small reeds, and one of their meals lasts for five or six hours. The women loved us very much more than their own men. All of the women from the age of six years and upward have their vaginas gradually opened because of the men’s penises.

_____________

I am thinking now that William Manchester in his description has taken some creative liberties from Pigafetta’s above account. The original Italian is lost, but from perusing thru this online digitized French copy, I think the above MLQIII link is the same as pages 98-102 here, https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/2017752

Do you speak French, Ireneo? I’m trying to figure out what that “spur” is. Tribes in Papua New Guinea have gourds, I don’t think this is the same set-up.

My allusion to Philippine hardware & software is mostly metaphorical, of course. The various primary sources cited by the various witnesses to the events between 16 Mar 1521 up to the exit of the Trinidad and Victoria are the data generated by the intersection of East meets West that is to become the new datum of the Filipino nation: the reports of the witnesses regarding the geographic stage (features of the archipelago, the real-estate) is verified and certified, the hardware so to speak; upon this physical stage, we can now trace the different complexes that are imposed by the different prisms (c. Karl) of human knowledge (anthropology, sociology, religion, governance, science, technology) IOW the software that we can now securely know is based on truth of, time, place and reflective thought.

PS. Lapu-lapu in all likelihood was past 60 yrs of age and his men, not he, killed Magellan. He was defending his bastard son as he died fighting; his remains were cannibalized by Lapu-lapu’s men as trophy. (I cherry-picked these bits).

PPS. The European discoverers of the Philippines were mostly of Visigothic extractions (Spain & Portugal); the litttoral Malay settlements were of Malay & Chinese (probably) provenance. Our Misses Universe, World, International, Earth are of Malay, Chinese, European physiognomies. The world is round indeed.

It happens to the best of the UNC, though I believe that LCX inspired you.

Re the comedy part and the corny stuff I have been asking you back then…

Irineo decided to retain it against the wishes of someone close to him.

Sometimes, we are given the latitude to express our sense of humor.

That is what I like about TSOH, so long as the timing is apt.

All the points in this article must be laid bare bcoz they constitute the Philippine “computer” hardware from which the Philippine software must be designed around for posterity.

Well, the Philippine condition has been described in different ways by different generations of observers both local and foreign, and there are both tight spots and saving graces even today.

For instance the FB post below shows a strength of the culture not being too far removed from the village – people planting on empty spaces in Metro Manila as food prices rise is part of the capability to survive. A weakness of that would be the lack of deeper systemic understanding, Joaquin’s Heritage of Smallness which often does find ways where bigness fails. The key to a better future may indeed be in organizing subsidiarity to meet today’s challenges, upgrade it from a consciousness that among many is probably still better suited to the situation in the 16th to 18th centuries than that of the 21st to a modern one, though modern need not mean imitating what fits elsewhere. Let us see.

https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=3424198737679885&id=100002693788139

I brought up these recurring questions in light of the pivot of events from an American hegemony to one in favor of China.

(This belongs under my previous statements: ” I formulated these questions way back during the Philippine Centennial year 1998. The VFA was then happening. … etc” Sorry.)

https://philippinesfreepress.wordpress.com/1961/03/18/the-death-of-the-guy-march-18-1961/ OT, Nick Joaquin’s reportage on Magsaysay’s death on March 18, 1957.

Sonny, you are one of the few among the blog regulars that experienced that time. Karl was 14 when EDSA happened while you would have been 13 when Magsaysay died and two million of 20+ million attended his funeral.

Irineo, the year was 1957, I just turned 13. The death of Pres Magsaysay was the first national tragedy my age group was exposed to. I was 2nd yr HS. The event was pre-empted for me by the death of my grandmother. I know the Magsaysay years were a heady time – the Huks were under check; There was general integrity in politics as we knew it; the controlled mayhem was only in sports (NCAA, UAAP, MICAA, Asian Games), UP was a warm bed of student activism, etc. There was literally plenty of room at a population of 32 million, foreign affairs were exactly that, foreign.

This kind of stuff is what Xiao does very well. Here is a short video narrating the death of Magsaysay including excerpts from comics and papers of then:

More stuff from the master’s thesis: (page 218-220)

Many people from surrounding districts were baptized during the

following week. Estimates as to the numbers are guesswork but

Transylvanus, from survivors’ figures, gives 2200.7 According to

contemporary accounts, Cebu extended four to five statute miles along

the seashore. It was a town of considerably larger size than any in the

surrounding islands and therefore probably possessed a correspondingly

greater influence through familial alliances. Magellan, probably

interpreted the size of the barangay to be the determining factor in

influence and so decided that establishing a strong Christian base in

Cebu would allow for the establishment of preeminence over the

surrounding islands and provide an effective defense against the

Portuguese. He assumed, as did later voyagers, that the social

hierarchy of the Cebuans also followed the European model and could use

this as an effective means of control. That this is the case is

indicated by Magellan, shortly after the baptism, attiring Humabon in a

yellow and violet silk robe signifying royalty, compelling the

neighboring chiefs at a formal ceremony to swear allegiance to the

Cebuan datu, and compelling Humabon, in turn, to swear allegiance to the

king of Spain. The most incongruous action in furtherance of this

strategy occurred when Magellan presented Humabon with a red velvet

chair and gave him instructions to have it carried before him at all

public ceremonies. 76

Having achieved the wholesale baptism of the Filipinos, Magellan

then insisted that they burn their old religious idols. The natives

replied that they could not because they were offering sacrifices for

the datu’s brother, a man very well respected, who was seriously ill.

That they were keeping their old idols because of the sick man was

probably a polite excuse to an impolite demand. The flexible, almost

pantheistic, nature of Filipino culture noted in chapter one of this

paper would not have abided the destruction of their idols–particularly

those containing the anitos of their ancestors. Prohibitions against

destroying idols had been recognized in the written Filipino codes that

have come down to us and the punishment for such offenses was death.

Magellan continued to insist that the Christian God would cure

the sick man if only he were baptized and the pagan idols burned. In

dramatic fashion, Magellan organized a procession to the house of the

sick man, who was in a coma. After baptizing the man, his wives, and

his children, a mattress, sheets, pillow, and coverlet were provided for

the man to rest on, as were sweet preserves to eat and perfume. The man

recovered and Pigafetta states the natives themselves destroyed their

holy places. Noone, however, doubts the veracity of this statement and

poses an alternative hypothesis. Pigafetta states that the natives

destroyed their own temples in a state of religious ecstacy crying out

“Castiglia, Castiglia”Th but it is likely that Pigafetta was being

purposely disingenuous. Noone proposes that, instead, the natives may

have been shrieking “Pastilan, Pastilan”–a term expressing great horror

or sorrow–as they saw their idols destroyed before their eyes by the

religiously enraptured Europeans.9

Combined with the Spanish actions regarding the idols another

source of friction with the Filipinos may have been sexual in nature.

While making no specific mention of such excesses Pigafetta does talk

about the mutilation of the male sexual organs practiced by the natives

and the preference for the Europeans which the native women had..

(LCPL_X, there he quotes the part you mentioned, there is also Page 225:)

Many theories have been put forth concerning the reason for the

ruse avd subsequent slaughter. As noted earlier, Pigafetta attributed

it to the mistreatment and resulting machinations of Enrique. Another

theory put forth by one of Pigafetta’s contemporaries posits that four

other datus of Cebu had threatened Humabon with death if he did not

drive out the Spaniards and so he relented to their demands. Most

significantly, however, an investigation conducteo by the king’s court

in 1522, after the arrival of the survivors, determined that the

massacre was due to the disreputable conduct of the men, in particular

Magellan, in Cebu–especially noting the mass conversions before

religious instruction, and the cases of sexual relations with and rape

of the Cebuan women.11

https://www.thediarist.ph/500th-anniversary-of-magellan-half-a-millennium-of-staying-the-same/ – by MLQ3:

..most of all what struck me was that in each Filipino painter—and probably, viewer (we all received the same basic programming in school)—lives a contradiction we’re so comfortable holding that we don’t explore it much at all.

This contradiction was best expressed back in 1979 by Nick Joaquin in a talk on Lapulapu he gave during a symposium in Cebu. Referring to the two chiefs, Humabon of Cebu and Lapulapu of Mactan, whose story bookends the life of Magellan and the start of our own formal history, he said they could be viewed like twins, permanently joined by their different reactions to the arrival of Europeans in our shores. Humabon welcomed the Europeans, submitted himself, to enjoy the advantages of association; Lapulapu rejected association with the Europeans precisely because it would place Humabon, whom Magellan had proclaimed overlord of all the chiefs in Cebu, over him (meaning, Lapulapu). For Nick Joaquin, here, on one hand, was the birth of the idea of a Philippines larger than, and including, its component island, and also, the birth of the refusal to dream big and prefer, instead, to stay small: after all, Joaquin pointed out, Mactan is a “microscopic isle,” yet even that place was divided into two, with two rulers; thus, said Joaquin, began “the ambivalence in the character of the Filipino.”..

..The key lies in something Ambeth Ocampo wrote in 2016, when he called attention to the book of Danilo Madrid Gerona, a historian from Bicol. Like all historians, Ambeth believes in going back to basics, that is, the original sources as far as we can tell, to strip away the layers of legend and misinformation that have stuck to the facts and often overshadowed them, over the ages. He pointed to Danny Gerona because he (Gerona) went back to existing records to try to piece together what, exactly, is known about Lapulapu. Among other things, Humabon of Cebu was related by marriage to Lapulapu of Mactan; and that, furthermore, Lapulapu himself was old, at the time of the Magellan’s ill-fated expedition to try to intimidate Mactan..

..The Filipino of today may find it hard to relate to the past of half a millennium ago but if you read even just Pigafetta’s account—knowing he was an admirer of Magellan—you will surely be struck by how familiar many of the power dynamics were, as observed by him and as chronicled by him. The need to obtain the local bigshot’s approval to engage in business; the absolute absence of any division between personal gain and political gain: indeed, how the two always go arm-in-arm; the perennial infighting, even among those closely-related with their own turf; and the violence not far from any disagreement.

If you read Pigafetta in April 1521 alone (see my timeline) you will find things we still encounter today: the influence of faith on power, the influence of personal gain, familial pride, and of force to settle disagreements, and if you add what the scholars are discussing and revealing to us, it makes one suspect that the real victor of Mactan wasn’t Lapulapu—because neither he nor his settlement made it past the return of the Spaniards—but the way we treat each other, and outsiders, too; whether Humabon or Lapulapu, or everyone else, you can see us, as in we, the people and in particular the lords and ladies of today, in those of half a millennia ago…

..Former Australian diplomat, Philip Coggan, happened to send me a video of an elderly man hopping between the familiar clacking bamboo sticks. But this was not the Philippines, it was Chin state in Myanmar, formerly Burma. The Karen people of Myanmar also have the same bamboo dance.

Across the border in Mizoram, North East India, which is believed to have been populated by immigration from Myanmar, the bamboo dance is also performed, as well as Bangladesh.

Further digging found it in Malaku – the Mollucas – and in an arc that includes the Indochinese states of Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, and neighbouring Thailand, as far as China’s southernmost island of Hainan and te south Chinese province of Guangxi.

It is notable that the dance is prevalent in tribal communities and hill people, a dance of the ordinary people rather than royalty, with the exception, perhaps, of Mindanao’s Singkil.

Given that spread, it seems unlikely that Tinikling spread from the Philippines to this vast geographical swathe of cultures. So how did it get here?

Remember that the islands that make up today’s Philippines were not isolated from the rest of South East Asia, they were historically part of the maritime trade routes of the region. Before direct trade between China and the archipelago were established in the 12th century, that trade went through the entrepot of Champa – Southern Vietnam and Cambodia..

..That suggestion would be stronger if there were other examples of Indochina-Philippine links in ancient times. And, indeed, there are.

Wherever tinikling-style dances are performed, you will find the sarimanok or Garuda bird as a potent symbol.

Consider the Tikbalang, the horse-headed spirit-demon of Philippine mythology. Horses are not native to the Philippines and did not appear until after the Spanish conquest. They were, however, known on the Asian mainland. And wherever you find Tinikling you will find the horse-headed deity depicted in museums across the world.

Australian academic Geoff Wade has noted the extensive similarities between Philippine writing systems and those of Champa and Cambodia.

Despite its ubiquity across the region, the dance seems to be absent from traditional art and sculpture, nor does it appear in travellers tales of the 18th and 19th Century. The first reference in the Philippines, for instance, is 1914..

..Yet, this dance may well pre-date the empires of Southeast Asia and its trade routes. It may have its roots in the great Austronesian expansion and colonisation that began around 3000 BCE that passed from Taiwan through the Philippines and onwards to the rest of Southeast Asia by 1000 BCE.

So, Tinikling could be an ancient vestige of that expansion and somewhere along that line the bamboo dance was created.

But if that was the case one would expect the dance to be represented among the archipelago’s indigenous non-hispanised communities, especially those of the interior and the highlands

Another potential route for Tinikling is slave-raiding. This was common in the region and it may well be that slave-raiders from the archipelago what was to become the Philippines brought back with them slaves who introduced the bamboo dance. The same Visayan raiders who assaulted coastal Chinese ports, and the Tausugs who sought alaves in what is now Indonesia, could have carried knowledge of the bamboo dance among the human produce they returned home with.

Or was it a dance at all? Could it have originated as an elimination game set to music, like today’s musical chairs – players being removed from the game as the clacking bamboo poles caught them until only one was left.

History is more than paper and papyrus, clay and copperplate, it is also in the songs we sing, the dances we dance, the games we play. in a lost language we have yet to decypher.

I’ve watched performances of TINIKLING and SINGKIL as performed, in cultural exchanges, by Filipino dancers in Mexico, Russia, Greece, USA, France. The “twin” nature is evident and exquisitely expressed by Filipino dancers: the dominant emphasis in melody & rhythm in TINIKLING, contrast the tonal bass beat of power in SINGKIL is unmistakeable. For my money, this contrast is best expressed by the Filipino artists. Hence the exhuberant applause wherever the venue. I’m unbiased, of course. 🙂

@LCX, some unresolved conversations that is related to the topic at hand.

Your question of how the Austronesians island hopped the Indian ocean, well they did not just hopped for sure.

https://www.philstar.com/opinion/2014/08/06/1354385/sailing-across-indian-ocean-south-pacific-balangay

5. The Austronesian migration is the widest dispersal of people by sea in human history, stretching from Madagascar in the Indian Ocean off the coast of Africa to Easter Island in the southern Pacific. What binds the people who populated all these far-flung islands is the Austronesian language. The Malayo-Polynesian languages, which include Tagalog, are derived from the Austronesian language. The word Austronesian comes from the Latin word “auster” which means south wind, and the Greek word “nesos” which means island. More than 400 million people speak Austronesian languages. The purest Austronesian languages are found in Taiwan where some one-half million Taiwanese Austronesians, the natives of Taiwan, still live today. The homeland of the Austronesian people is Taiwan.

6. How did the Austronesians migrate over vast distances in the Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean and South China Sea? The answer is the outrigger sailboat — called balangay in the Philippines, vaka in Hawaii, vawaka in Polynesia, and vahoaka in Madagascar. Prof. Adrian Horridge, in his paper “The Austronesian Conquest of the Sea – Upwind (The Austronesians,” edited by Bellwood, Fox and Tryon, 2006), writes: “The built-up dug-out or planked canoe with an outrigger and sail has been the principal technology for survival and colonization for the sea-going peoples who spread over Island Southeast Asia and far over the Pacific for at least the past few thousand years. We deduce this from the present and presumed past distributions and structures of the canoes. With the ability to carry fire, family, dogs, chickens, tuberous roots, growing shoots and seeds by sea, the Austronesians eventually occupied the Pacific Islands, travelling into Melanesia about 3,500 years ago and onwards into Polynesia.”

I had a chance to watch a video in Taipeh International Airport en route to Manila. The video was about the diverse minorities native to Taiwan. This was the most graphic coverage I had seen regarding the Out-Of-Taiwan theory, the southward trek of these peoples across the Strait into northern Luzon through to points to Bicol, the Visayas and Mindanao.

I am curious about the cultural minorities’ in Taiwan current situation, glad you were able to share.

Another topic I opened up elsewhere in TSOH, the caravans of ancient Pangasinan.

From maritime culture to commerce in land.

Click to access 978-5-88431-174-9_20.pdf

Another gem of Filipiniana, Karl. Thanks for re-sharing. I missed this one about the richest province of Region 1. Pangasinan is very important to the Ilocanos who found a haven for their industry and work during the great emigration of Ilocanos from the north (1830s) into San Fabian and other points south and east across the Bued River; access towns (Rosario to Baguio into the Cordilleras used to belong to Pangasinan. It was annexed as the southern tip of La Union. It was not only the cart caravans that weere a boon to other towns. No fiesta was complete in the Ilocos without the itinerant “Big Band” sound from Pangasinan. 🙂

Thanks

I had you in mind Unc, because Irineo said that he hoped that you would say more about that. You were busy late last year with your health and chores.

Details on Gomburza by Xiao. Didn’t know until now how high they were in the Church hierarchy and how learned they were. https://youtu.be/f_1pOhNbcSc

thanks, i guess if they were nobodies they would just be made to disappear.

The aha effect for me is that the picture some of us had about Padre Damasos and Salvis being the only higher ups in the 19th century Church hierarchy on the islands is somewhat a false impression.

The next question would be how many % of higher positions in the Church (and the Spanish colonial admin, for that matter) were held by non-peninsulares, how many were held by insulares and how many were with non-Kastila.

Next question that will be answered soon.

Eminent Filipino Jesuit historian, Fr John Schumacher, SJ, has whole book on GomBurZa. Will dig for my copy and share. (@Irineo: I think Rey Ileto studied under him at the Ateneo).

bio: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/547292

Very good, Unc!

Inday Espina Varona: “??? Who writes his speeches? The Spaniards were not the first foreigners visit the Philippines. In 1521, Muslim sultanates already established in Mindanao; religious teachers from around the Persian Gulf brought in Islam. The Chinese had also been trading for centuries.” as a Tweet in response to Dutz saying “Duterte: Until now, we are also celebrating because it was the first time we saw foreigners in our native land. That alone speaks a volume of stories.” https://twitter.com/indayevarona/status/1372475258238734338

She follows with “Islam reached the Philippines in the 14th century via Muslim traders from the Persian Gulf, Southern India, and several sultanate governments in the Malay Archipelago… at least 200 years before Spanish explorers came.” https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2005/01/how-islam-got-to-the-philippines

Inday continues: “Dear speechwriter and Duterte, you didn’t check with NCCA and historical commission?! Heto Sulu was the first Muslim community in the south to establish a centralized govt, the Sultanate of Sulu in 1450.”

http://gwhs-stg02.i.gov.ph/~s2govnccaph/subcommissions/subcommission-on-cultural-communities-and-traditional-arts-sccta/central-cultural-communities/the-history-of-the-muslim-in-the-philippines/

“Even the PIA has written about ancient Chinese traders … China began trading in the Philippines as far back as 7th century AD w ancient coins and porcelain as trading goods through the Galleon trade. (Mas substantiated ang 11th century up, in next box)” https://pia.gov.ph/index.php/news/articles/1022429

“The Chinese exchanged silk, porcelain, colored glass, beads, iron ware for hemp cloth, tortoise shells, pearls and yellow wax of the Filipinos; became the dominant traders in the 12th and 13th centuries during the Sung Dynasty (960-1279 AD).”

https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/philippines/history-early-china.htm

“Just to be clear, trading does not mean ownership of our waters or our territories. Hindi pagmamay-ari ng Tsina ang mga karagatan natin.”

“It’s really shameful for Duterte to peddle such a careless, lazy lie. He’s from Mindanao. He just ignored the history of our Muslim Filipinos. Even the most conservative history books acknowledge Muslim resistance because they had long been established societies.”